soulellis.com / writing / feb2021

Paul Soulellis

URGENT PUBLISHING AFTER THE ARTIST’S BOOK: MAKING PUBLIC IN MOVEMENTS TOWARDS LIBERATION

We’re here at a conference devoted to the artist’s book, at an enormous art book fair that’s considered to be the ultimate destination for artists who publish. And we’re here to take the temperature, so to speak, as the title of this event tells us, around art book criticism and scholarship. We’re taking the temperature during a pandemic, during the radical turbulence of racial injustice, police brutality, political turmoil, and climate emergency—a feverish backdrop to the task at hand. So I’d like to begin by acknowledging that for the next 40 minutes I’m going to present this talk within this very specific, very real context of multiple, overlapping, and intersecting crises.

Let’s start by examining one of the more foundational statements about artistic publishing, written in 1976, the same year Printed Matter was founded. It’s from writer and curator Lucy Lippard, one of its co-founders, and it appeared in this issue of Art-Rite, a periodical that was founded and edited by some of her Printed Matter colleagues.

In this statement she expresses optimism around the politics of publishing as an artistic practice. She’s writing about the potential for artists’ books to act like propaganda, specifically around feminism:

“One of the reasons artists’ books are important to me is their value as a means of spreading information...

“I’m talking about communication but I guess I’m also talking about propaganda. Artists’ books spread the word—whatever that word may be. So far the content of most of them hasn’t caught up to the accessibility of the form.

“The next step is to get the books out into the supermarkets, where they’ll be browsed by women who wouldn’t darken the door of Printed Matter or read Heresies and usually have to depend on Hallmark for their gifts.

“I have this vision of feminist artists’ books in school libraries (or being passed around under the desks), in hairdressers, in gynecologists’ waiting rooms, in Girl Scout Cookies...”

Almost 50 years later, I think we can say that Lucy Lippard’s vision of artists’ books ensconced in supermarkets has finally arrived, although not in the form she anticipated. Today, rather than finding Heresies at the Stop ’n Shop, we download it and carry it with us while running our errands. We find artists getting the word out about feminism and race and politics there in our feeds. But this works so well not because the zines are for sale, but because we are. We are the product—or rather, our behavior and data are.

Lippard’s vision has been turned inside-out—instead of artists taking over public space with publishing,

we have algorithmically-sorted feeds acting like vast publishing machines that engulf us,

watch us, and listen in while we post, shop, and consume. And of course there’s no need to actually go to the supermarket—we can do that right there in the feed.

Who controls the narrative then, in this distorted version of the empowered artist, who has so-called ‘free’ access to these unlimited tools?

These feeds that we care for and nurture and consume are precisely engineered by big tech companies to manipulate our attention, while at the same time claiming that their publishing platforms have finally democratized the dissemination of information, lol. We know this isn’t true, and that these tools are far from perfect, far from pure.

Yet still, we fight to protect and consume and occupy them. It really is a surreal thing to think about, this inside-out, disembodied version of Lucy Lippard’s dream of spreading the artistic word.

I’m also thinking about Lippard’s famous quote in relation to urgent publishing, because there is an undeniable sense of urgency right there in her language. She’s expressing the political potential for artistic publishing, art as propaganda, publishing as a way to shift or change perspective.

There is some truth to this in our current reality, which complicates my simplified read of big tech publishing. Artists are pushing art to the masses like propaganda, alongside everyone else and their messages, including and perhaps especially her Hallmark moms. Her awkward characterization of those women who wouldn’t “darken the door of Printed Matter” sounds misguided or even offensive today, and for me it brings up questions about Lippard’s own position in writing her statement, around class, race, and feminism in the mid-1970s.

Lippard’s statement, and our connection to her through this fair, sets the stage for us to take the temperature today. She dreamed of a politicized, maybe radicalized publishing future through artistic means. But publishing has always been political—artistic, academic, commercial, or otherwise. Publishing compels, persuades, informs, attracts, confuses, scripts, and manipulates. To publish is, fundamentally, a political act.

In moments of crisis, as we’ve experienced so deeply in the last year, we see not only artists, but community organizers, scholars, poets, and activists collectively engaging with different modes of publishing to urgently document and communicate what’s happening, in real time. They’re not at the supermarket—they’re in the street. And they’re at home with us. Today, the artist’s propaganda that Lippard hoped for is right there in our feeds when we wake up in the morning, making the distinction between what is or isn’t right for us, or radical enough, or too political, or not artistic enough—or what is or isn’t publishing, even—an overwhelming condition, and much more difficult to navigate.

Here’s an artist’s book by Lawrence Weiner, solidly regarded within the artistic publishing canon, and whose work has been featured at Printed Matter since the day it opened.

Here’s his most recent work—a collaboration with Virgil Abloh for Louis Vuitton. For their Fall-Winter 2021 collection they “plastered his statements across accessories,” which we can see in these stills from a highly stylized film that was released online just a few weeks ago to introduce the work. Dramaturgy and scenography is credited to Kandis Williams of CASSANDRA Press, one of the exhibitors here at this fair.

They’re just part of a vast team of highly creative and sought-after artists, poets, musicians, and cultural producers, coming together to sell four thousand dollar bags. How do we approach artistic publishing now, in relation to a project like this? In relation to this economic reality? How do we reconcile the artist, the propaganda, and the supermarket, here?

I’m purposefully creating confusion with this example in order to question some of the terms we’re using here at this conference, like artists’ book, artistic publishing, and publishing as artistic practice. I’m well aware of where this language comes from, and what it means in a classic sense. But rather than control and cement these terms into a kind of self-reassuring certainty, I think it’s crucial that we problematize this language. And these images.

Especially here at this conference, at this fair. Who gets to use the word artist? What qualifies as artistic publishing, when this kind of commercial and cultural production is the context that we’re working in—selling $250 photobooks, or $14,000 artists’ portfolios,

or tabling next to a 10.5 billion dollar corporation at the art book fair? Why look at artists’ books at all, right now, in crisis?

Like the rest of the art world, artists’ books have been absorbed into every corner of corporate, commercial, and institutional politics. AA Bronson noted this in an interview in 2015, and talks about an interest in things that are done less institutionally, on the fly. “Artists are using different technologies; books like this can occur and be printed in a more casual way.” (emphasis added)

I propose that we examine this more casual way of publishing, stretching beyond books and beyond the artist’s practice even, and open up this space to a broader understanding of how folks shift our view by disseminating urgent, creative material.

Writing about queer publishing in this context of cultural capitalism and institutionalization, Darian Razdar says that “...subsuming radical practices into dominant structures perpetrates more harm than it reduces. Non-profits, museums, cultural corporations, style magazines, chic developers, and governmental arts councils are all complicit (to varying degrees) in the exploitation of transgressive art for capital accumulation.”

Instead of focusing on these institutions and the exceptional artist publisher as solo producer, let’s think about publishing below, outside of, against, or after capitalism. And acknowledge the complex reality of how it is that artists who make books are even able to survive today, under enormous precarity.

Publishing has always been used to dominate and exert control, as one of the principal tools of hegemonic power and colonization.

Treaties, tracts, maps, executive orders, regulations, laws, textbooks, branding guidelines, entire libraries, algorithmic feeds—

these are just some of the ways in which the construction and distribution of knowledge through acts of printing, publishing, and archiving have been used to control the narrative. And in so doing, to marginalize, authorize, police, harm, and erase. Especially in today’s special blend of accelerated surveillance capitalism.

So, there’s good reason to try to understand the political potential of publishing right now, especially when it can be used to loosen or push back against the grip of hegemonic power. Because while publishing can most certainly be a tool of the oppressor, the ability to circulate stories and information in public space is also one of the superpowers of the underserved.

As a means towards the empowerment of those who suffer most under oppression, independent publishing enables truly alternative ideas to be seen and heard, outside of corporate, state, and institutional values. Sometimes it’s happening right there in the open, on the same exact platforms where others are doing the most harm.

Sometimes it’s elsewhere, in less visible spaces. So while we’re here to think through and examine and question the form of the book, I would like to suggest that we also put that safe word aside, and instead, think platform.

With so many ways to “make public,” and an endless range of publishing technologies and platforms becoming available, publishing as empowerment is now more possible than ever, but I’m going to have to leave the artist’s book behind to go further with this thought.

Which brings me to the title of my talk—“Urgent Publishing After the Artist’s Book.” The radical potential of publishing, artistic or otherwise, is the part of Lippard’s quote that I’m most hopeful about. How we might share stories, legitimize thought, propose alternatives, and collectively imagine other futures—by, with, and for oppressed communities, especially Black, Indigenous, people of color, queer and trans folks, disabled folks, immigrants, and everyone else left out of normative history-writing and speculative future visioning.

From live-streaming to animal crossing protests to community organizing on discord, today’s independent publishing culture enables those with access to basic tools so many options for creatively disseminating radical ideas. And to use the circulation of published material as a way to gather in communion against oppression. This happens at every scale, from individual empowerment to global coalition building. Urgent, radical publishing is one of our most powerful tools in the movement towards liberation.

Yes, let’s leave the traditional form of the artists’ book aside for now. Instead, we’ll draw upon decades of radical, anti-capitalist thought and collective action, focusing on specific moments of “publishing as interference” produced within the Black Radical Tradition, feminism, abolition, co-operative organizing, queer and trans liberation, and queer theory. This other history of publishing is sometimes approached through an art or design or poetry lens, but it’s almost never the primary focus when telling that story.

By looking closely at the interference, and at the specific gestures and acts of publishing that interrupt and agitate, I want to shift our attention away from the commodified, supermarket-view of publishing as the production of objects. What if this most famous diagram by Clive Phillpot had been drawn to depict actions or gestures, rather than consumable pieces of fruit?

Looking closely at specific acts of radical publishing as interference enables us to see the labor involved, and the values that emerge from social publishing ecosystems that depend upon collaboration, participation, communal care, and mutual aid networks. Values that encompass a new ethics and a politics of making public, rather than endless variations on old publishing models.

Let’s look at a few examples.

Much has been written about the visual impact of The Black Panther newspaper, and Emory Douglas’s legacy as the party’s Minister of Culture and the newspaper’s art director, designer, and main illustrator. As well as the political content published in the more than 500 issues of the newspaper, which was the most widely read Black newspaper in the United States from 1968–1971.

How the newspaper was distributed is less discussed.

“Wednesday night was when the paper came out. Every Panther in the Bay Area came to help ‘get the paper out.’”

Black Panther Party members themselves were responsible for dispersing the news, and would sell the paper in laundromats, street corners, and other public spaces. Sounds familiar! This is the radical publishing future Lucy Lippard dreamed of, years before she wrote those words.

The cost of the paper was 25 cents, and sellers would keep a dime from each sale. As a co-operative model of publishing, the dissemination of radical thought was closely dependent upon each members’ participation as a distribution point in a peer-to-peer network. I propose that we see The Black Panther newspaper model as an early example of urgent, mutual aid publishing. It’s the radical labor here that’s often overlooked, in favor of the end product. Participation in The Black Panther publishing ecosystem was supported by the act of delivering it. Each distribution point also becomes an opportunity for conversation—to learn, interact, and engage between people.

As a shared practice, The Black Panther newspaper was not just a published product, but an alternative publishing economy that prioritized care and community need, and this was negotiated and fulfilled communally through acts of mutual aid. The exchange of money enabled the newspaper to continue printing but it also directly benefited those who labored in its distribution. The act of publishing itself was intimately tied up in the values and politics of its content.

The form was conventional—it’s a newspaper—but every other aspect challenged expectations, from its politics to its design to its method of delivery to its economic model to its social impact. It was urgent publishing in the physical timeliness of its delivery in public space, and in the necessity to gather and engage in the exact moment of exchange. This was radical publishing because it interfered with the conventions of white-controlled, white supremacist mainstream media, by amplifying the conversation around racial injustice. It gave voice to Black communities in crisis.

Later in the 70s, The Combahee River Collective emerged in Boston. The Collective was a Black feminist lesbian organization, and it published what would become a groundbreaking text: “The Combahee River Collective: A Black Feminist Statement.” The Statement announced their politics as separate from and more radical than the group they emerged from, the National Black Feminist Organization.

Barbara Smith was one of the co-founders of the Collective, as well as of Kitchen Table Women of Color Press. In an incredibly detailed oral history from 2003, she describes the formation of the group and the writing of the Statement:

“And people know about the Combahee River Collective because of the statement and because I was committed even before becoming a publisher to have that appear in as many places as possible around the country and the world.”

Later in the interview, Smith describes making photocopies of the text, after it was published for the first time, in order to distribute it at a conference.

“it was going to that conference and coming prepared with copies of the Collective statement that we had xeroxed, that’s what gave me the idea to do the Kitchen Table Women of Color Press Freedom Organizing Pamphlet Series.”

Smith’s photocopying of the radical text and delivering it in person—“coming prepared” to a new audience—was both casual and urgent, and probably didn’t look or feel like publishing in the moment. But it was a necessary and timely act of dissemination.

She speaks of preparation, a readiness to “spread the word” with the Statement, photocopies in hand. It was an urgent intervention (within the time and space of the conference), more a quick gesture than formal “publishing,” but without question the distribution of a radical text. She used modest, available tools (a xerox machine), and her own labor, to spread the word. It was a timely re-distribution, a quick re-publishing on top of a slower one, entirely outside the academic, commercial, or alternative publishing worlds. She did what had to be done.

It was around this time that Smith founded Kitchen Table Women of Color Press, after a phone conversation with Audre Lorde in October 1980, where Lorde said to her, “You know, Barbara, we really need to do something about publishing.”

Smith goes on to say:

“As feminist and lesbian of color writers, we knew that we had no options for getting published, except at the mercy or whim of others, whether in the context of alternative or commercial publishing, since both are white-dominated.”

From the urgent need to write and publish the Combahee Statement, to the xeroxing and hand-delivery to new audiences, to the necessity of starting a press that would work towards a new Black feminist publishing—the extended moment described by Smith suggests enormous labor and determination. These acts and artifacts are the result of a powerful commitment to communal care through the distribution of radical ideas.

Along with The Black Panther newspaper and Kitchen Table, many other activist publishers emerged from crisis, resistance, and liberation in the late 1960s and into the 90s, from Fredy and Lorraine Perlman and their Black & Red press at the Detroit Printing Co-op,

to the early queer publishing collective Come!Unity Press in NYC in the 1970s, with taglines like “Survival by Sharing,” and “Press for a Sharing Culture,”

to Gran Fury and ACT UP,

Queer Nation,

and the queer and trans zines and newsletters of the 80s and 90s, like Gendertrash (1993–95).

I’d like to bring one more moment into this timeline. It’s an image that attracted wide attention in the context of the AIDS pandemic, and the necropolitics of the Reagan administration in the US, which targeted gay men and intravenous drug users. On October 11, 1988, artist David Wojnarowicz attended an ACT UP action at the FDA in Washington, DC, wearing a denim jacket with lettering that spelled out the following message on his back:

“IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.”

I see this jacket (as well as this photograph of Wojnarowicz wearing it), first as an act of protest. It speaks within and on behalf of the collective—the ACT UP activists assembled at this particular moment, and the vast community they represented. It speaks as an urgent gesture of publishing, manifesting dire language in public space. The wearing of the jacket uses the very body that is the subject of its message, the body that will die four years later from this disease, as the platform for its dispersion.

This jacket is many things—it is performance, it’s graphic design, it is a shared plea, it is a political protest. It’s an urgent artifact charged with meaning and power in the specific context for which it was crafted. It exists as a fleeting performance in that moment, an urgent message that announces a call for refusal (FORGET BURIAL), and the potential for radical action (JUST DROP MY BODY). It continues to deliver these messages as a specific photograph that documents the event, circulating more than 30 years into the future and speaking to us today, in relation to other pandemics.

It’s the artist’s labor that needs to be noted here—an urgent call to interfere, against acceptance and cooperation. As we trace an incomplete history of urgent acts of publishing, I propose that we identify the labor surrounding this jacket, created and worn at this protest, and the photograph that recorded it, now traveling through time and across networks, as a powerful example of publishing’s radical potential to interfere with and loosen power. It does so defiantly, outside of any commercial model, outside the supermarket, standing far away from capitalist, heteronormative definitions of artistic success.

The Black Panther newspaper spreading the word, Barbara Smith spreading the word, David Wojnarowicz spreading the word. We should resist seeing these moments of interference as singular, disconnected events in the history of independent publishing. Instead, let’s consider them as one extended moment of urgent formation. A formation that connects those acts to each other and to many other acts and gestures in an ongoing, liberatory movement, a movement that expands into our present and beyond, spreading the word. This is a different history of artists getting the word out, as propaganda and as interference, far removed from Ed Ruscha, Sol LeWitt, Seth Siegelaub, and the Printed Matter origin story.

Antifa, abolitionist, anarchist, activist, queer, mutual aid, and other types of liberatory publishing—made by artists and non-artists alike—continue this extended moment of urgent formation today, moving it towards a queer, never-arriving utopian horizon. This extended moment produces artifacts that might seem unremarkable in form. But the photocopies, PDFs, spreadsheets, tweets, GIFs, memes, zines, banners, flyers, and pamphlets are only a part of the story. We must also understanding the enormous labor and risk involved in their making, in their collective sharing, and in their ability to agitate. This is urgent publishing that’s local, peer-to-peer, and decentralized, whether for an audience of 5 or 5 thousand.

I propose that we locate the future of independent publishing right here in this continuous trajectory that emerges from the long fight for justice. Let’s widen our view to include communal care, potentiality, and liberation beyond the horizon—through the distribution and amplification of radical ideas in the public sphere.

To follow this trajectory into the present moment—let’s pause and step away from our hyper-focused view on exclusive gatekeeping institutions, like academic and commercial publishing, art book fairs, the artist’s book, book art, and the legacy of artistic publishing in a traditional sense. I propose that we look away from the idea of “alternative” art world spaces altogether,

away from commercial spaces and heteronormative, market-based success, and refuse to locate the future of urgent, radical publishing in relation to these structures at all.

It’s a difficult proposal, I’ll be the first to admit. We certainly can’t blame ourselves for wanting to bring our books and zines to market, and perhaps to make a profit. I’m not suggesting that we never sell our work. But to what end? Who profits, and how? What does it really mean to participate in the art book fair economy? Is it sustainable? At what cost? Who does this economy favor and serve—and who does it exclude?

While admission to Printed Matter’s fairs remains free to the public, the application process for exhibitors is extremely competitive. More than a thousand vendors applied for 350 spots at the last in-person fair, in 2019.

Once accepted, participants paid fees ranging from $150 for a small table in the “zine tent” to more than $1,200 for premium indoor tables, to more than $10,000 for larger project spaces. In 2019, Printed Matter hosted exhibitors from 28 countries, and attracted 35,000 visitors in a single weekend. If there was ever a global “circuit” for independent, artistic publishing, it is undoubtedly these art book fairs, especially in terms of audience and potential for sales. Images of crowded art book fairs are used again and again to demonstrate the popularity of zines and artists’ books, and as evidence of the resurgence of print and physical media. The fairs host a vibrant community of vendors and participants who discover, socialize, and connect.

At the same time, and this needs to be said clearly: this is primarily a space of commerce. Unit sales and movement of product are not only desirable but crucial in order to maintain one’s position in the art book fair economy. The art book fair is not separate from the art market—it is an alternative extension of it that requires and depends upon the same activities like branding, marketing, and selling, even if at a different scale. Instead of infiltrating the supermarket, we’ve set up our own, inside a museum.

While no one expects to become wealthy selling zines at art book fairs, the pressure to “break even” in order to recoup what are often tremendous expenses is enormous. There is little room for failure in this model, something many of us know all too well from experience.

The year-round scheduling of the fairs establishes a steady, seasonal rhythm for artistic publishers that discourages urgent or disruptive acts, in favor of planned, well-organized projects that have the potential to sell, marketed and approved well in advance.

All of the good energy and support generated by and for the independent publishing community at these events is enormous and undeniable—they’ve changed my life and my work. Still, the art book fair is a hustle space, often at the expense of mental and physical health, which suffers for many under the enormous pressure to remain visible and viable, and to perform successfully at the market.

I can’t overstate this enough: this is especially true for historically marginalized and minoritized participants who must negotiate enormous issues around visibility and self-care in public space on top of everything else. The hustle space of independent, artistic publishing, centered firmly on the art book fair, leaves little room for un-profitability, experimentation, or failure. There is only so much tolerance for radicality or disruption, here at the art book fair, before the economics become untenable.

I’ve already asked you to put aside the two words that have brought us together at this conference: artist and book. It’s not because I’m trying to avoid something, but because we desperately need to widen our view. By we, I mean our community of folks who publish, as well as the critics and scholars and students and collectors and anyone else who believes in the power of, as Lippard put it, “spreading the word.” I’m asking us to shift, maybe uncomfortably so, from taking the temperature of art book criticism and scholarship, to considering the future of independent publishing during crisis, against and beyond capitalism.

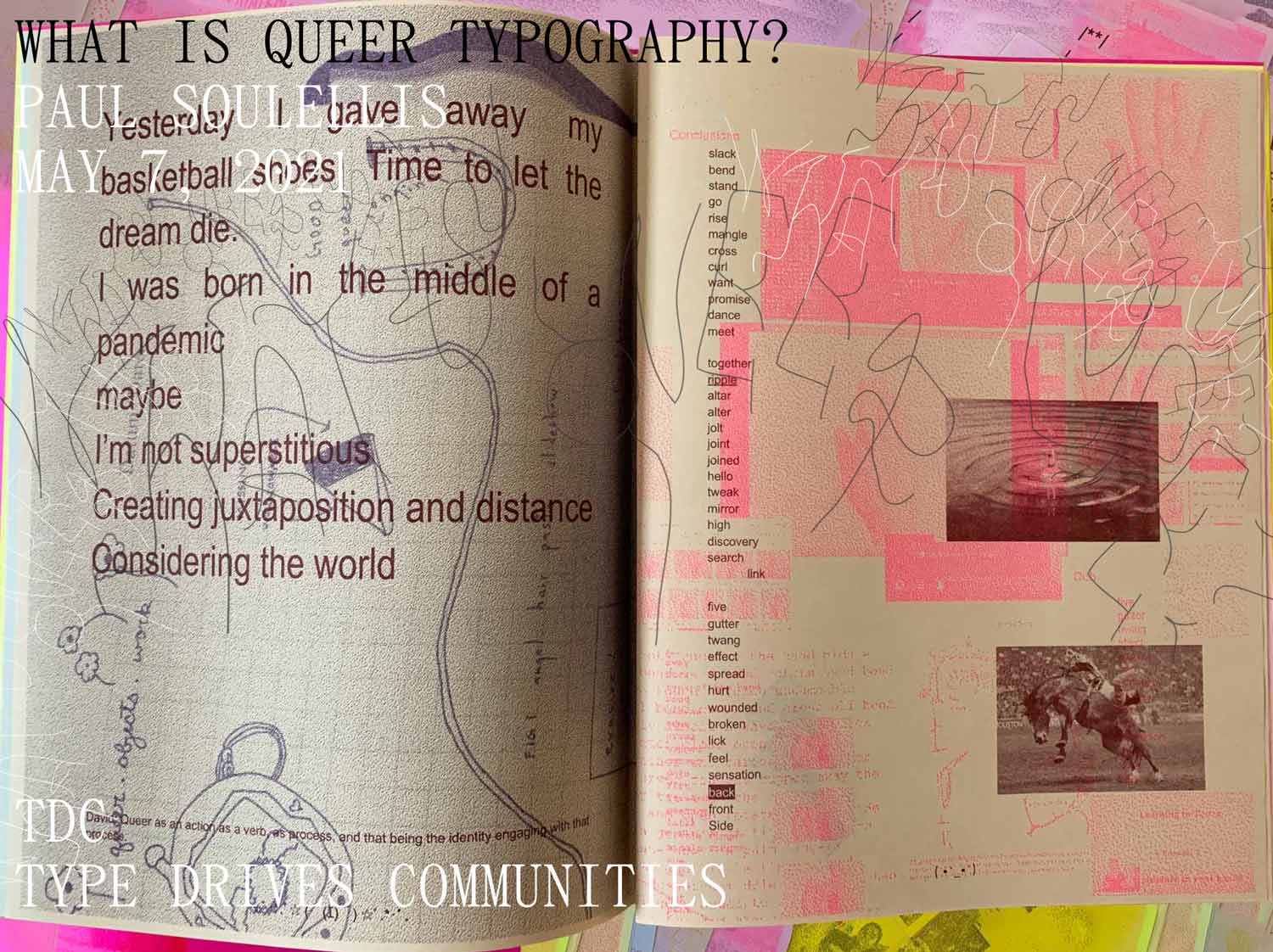

To do this, we desperately need new language. We need new forms of discourse to get at what it means to create and share today. We need to examine images of protest and performance and social media and zines, at a conference devoted to the artist’s book, and connect them to the larger moments of urgent formation I’ve sketched out, extending from way behind us, far into the future. To do so we need to depart from the familiar. We need to approach this culture of making on other terms. Terms that aren’t grounded in the values of art world commerce, like accumulation, exceptionalism, and individualism.

Writer and poet Fred Moten, with Stefano Harney, offers us a way through this. They call for the abolition of both the individual scholar and the lone artist as sovereign figures. They ask us to focus instead on collective work—as Moten puts it, from the I to the we—and the notion of shared practice as a way to satisfy the wealth of communal needs. In a sermon Moten delivered last year, just before the pandemic, he spoke about gathering in call and response as a “radical turbulence” that has a tendency to overturn the order of things, that must be honored and unleashed and cultivated. He says that “gathering makes a grammar all its own.”

Evidence of this gathering, this grammar all its own, is vivid and plentiful all around us, in our recent periods of deep and overlapping, intersecting crises.

The evidence is in the urgent, radical messages shared in public space, acts of publishing that are far removed from traditional definitions of artistic practice found here at the art book fair, or in specialty bookshops; often not looking like publishing at all.

Rather, it is the invisible, illegible, or undervalued labor of organizing and activism by historically marginalized people and underserved communities that now fuels a new ethics and politics of urgent, collective making.

As COVID spread to the US in March 2020, and then during the late spring uprisings around racial injustice and the murder of George Floyd, digital platforms like Google Docs, Instagram, and TikTok exploded with urgent acts of writing, organizing, protest, performance, and sharing.

Mutual aid spreadsheets, toolkits, petitions, letters, manifestos, livestreams, funding directories,

testimonial archives, poetry, murals, reading lists, multi-panel narratives, and educational guides flooded and nourished our feeds.

Along with printed newspapers, newsletters, zines, memes, pamphlets, hand-written signs, articles of clothing, and risograph prints, we need to acknowledge the power of these urgent artifacts of conflict and liberation, circulating radical messages on behalf of communal aims, across all kinds of networks, new and old.

Some of these artifacts are made by artists but also by writers, activists, abolitionists, students, organizers, and community leaders. These urgent acts and artifacts confuse the traditional boundaries between artist, publisher, and audience.

Urgent publishing against and beyond 21st century hyper-capitalism continues this trajectory against the “acceptable” and against institutional “rules of cooperation.”

Urgent publishing today is queer, non-cooperative publishing in that it interferes with and explicitly refuses to play by heteronormative definitions of success.

At this year’s fair, happening as we speak, these are some of the small presses and collectives and projects that embody this important work of gathering in call and response, doing the slow work of community building, organizing networks, and queer, anti-racist, non-cooperative, publishing. This year, the fair feels different. Overnight, we’ve set up e-commerce websites and become mail-order businesses. But there’s a beautiful intimacy to the fair that’s taking place right now, that I didn’t quite anticipate, and it has something to do with network culture, and networks of support. It reminds me of early internet days, not exactly in a nostalgic way, but very hopeful, of-the-moment and of-the-future. There are so many options for navigating this year’s fair, and I feel like we’re seeing each other and looking out for each other, here in the market, in the midst of crisis.

I’m here with this new, informal, but very intentional community of queer makers that gathers around the non-profit publishing space that I direct, Queer.Archive.Work, here in Providence, and online.

and we’ve put some of what I’m discussing today into practice with a new publication that we’re releasing right now at the fair. half of the edition is being distributed by the contributors themselves, the other half distributed for free or trade to Queer, Trans, and BIPoC folks. Institutions, however, pay.

Elsewhere, I’m enormously inspired by the work of Binch Press, here in Providence,

Ocean State Ass,

American Artist,

Demian DinéYazhi´,

nat pyper,

Brown Recluse Zine Distribution,

Unity Press,

Authentic Creations Artistic Apothecary,

Nafis White,

BUFU—By Us For Us,

Kenneth Reveiz,

and Indigenous Action Media. Among many others.

But also, maybe most importantly, we need to acknowledge all of the folks who are gathering, making, and sharing from positions that aren’t necessarily in our familiar spaces.

These are artists and students and activists you may never hear of, who work and labor and continue to make out of necessity. For them, spreading the word isn’t safe. It isn’t a choice, or a career move, but a matter of survival.

Neo-fascism and neo-liberalism are consuming everything in their paths, including “resistance.” The idea that graphic design, book arts, or “publishing as artistic practice” can be radical is no longer an option. I reject these efforts. Instead, let’s create and circulate radical messages, and form new kinds of publics, far away from traditional institutions of knowledge production and disciplinarity. These messages will be illegible to some. Urgent artifacts are not easily digestible and they resist canons and containers.

This 3D scan of the defaced Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, turns a powerful moment of embodied resistance and protest in public space into something else.

It’s strange to call this OBJ file from June 2020 a publication. But this file, posted to sketchfab, is a compelling, creative act that can be read, downloaded, studied, shared, copied, archived, and spread. It is a powerful act of publishing, an urgent artifact that needs to be studied, protected, and preserved.

Why aren’t we looking closely at the thousands of contributions to this unlikely, unfamiliar, but timely publication, and this digital file that assembles them, and how it circulates on an open source platform, in order to better understand how and why we share today?

Let’s gather as we are right now at this conference, and shift from the I to the we, to the communal work of shared practice. We’ll find new energy and motivation by stepping away from traditional notions of publishing as an individual artistic practice. Away from the market-facing domination of the artists’ book as it’s evolved during the last fifty years.

Let’s find hope and inspiration in the messy, slow work of artists’ collectives, activists, poets, and organizers working today, engaged in the principles of urgentcraft. And in the multiple histories of publishing that are yet to be written, choosing to focus specifically on those who are left out, those who work outside of art world whiteness, those who devote themselves to making public as an ongoing, urgent formation towards justice and liberation.

This is an ethics and a politics of urgent making that I’ve sketched out, and this is our call to shape, evolve, share, and manifest these ideas within our everyday work.

Center for Book Arts

Contemporary Arists’ Book Conference

February 27, 2021