soulellis.com / writing / feedtime

“Feed Time”

Paul Soulellis

Commissioned by V-A-C Zattere, Venice and published in Time, Forward!, Omar Kholeif, editor (2019)

Network culture is a smooth texture. It’s no longer a destination but an edgeless condition infusing every aspect of daily life with distortion and disorientation. In the past, the network was a discrete destination, a location found by “going online.” Today, it’s a continuous state of connectivity, a delirious flow between humans, interfaces, and algorithms. It’s a condition that emerged out of American counterculture in the late 1960s, first in print with Stewart Brand’s “back-to-the-land” Whole Earth Catalog and then in the earliest networked communities, like the Bay-area bulletin-board service Community Memory and The WELL (Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link). Fifty years later, ubiquitous connectivity has evolved to support ideologies of data, profit, speed, and prediction. Once the promise of radical communalism, today’s network is an engine of cultural sameness, packaged as authentic individualism. Twenty-first century surveillance capitalism is thriving under the rule of GAFA (Google Apple Facebook Amazon) and its astounding ability to convert user data into prediction futures. It’s a market that trades in human behavior and addiction, our insatiable desire for never-ending connectivity, convenience, and the sensation of flow. In return, we feed our preferences into enormous ecosystems of profit and inequity that seem to stretch further and further away from the internet’s feel-good origins. Is there any way to resist?

Let’s characterize the experience of living with these platforms now as ultimate smooth flow, a numbing sensation where individual tweets, images, and headlines no longer matter. Rather, we swim through endless feeds and streams that serve up enormous accumulations of information in real time. We tend to these feeds, constantly adjusting and caring for them as though we own and control the data. The old publishing paradigm of the individually-authored post (the blog post, the daily post, “keep me posted”) is over. With it, the ability to discern (chronology, context, value) has been reduced to simplistic choices around style and accumulation. Ultimate smooth flow is an overwhelming condition, characterized by a fluid, stretchy sense of time and space. We negotiate new kinds of relationships with algorithms that keep us continuously engaged so that our data resources can be mined, a frenzied condition that we crave at the cost of peripheral vision and individuality. Interfaces have become thinner and thinner, approaching invisibility; they’re transforming into conversational scenarios (Siri, Alexa) and gestural experiences (Face ID, VR, fingerprint scanning), where any previous awareness we may have had of authorship and authenticity has evaporated. These interfaces are becoming less visible, but their power is increasing—the engineers, algorithms, and corporate tactics of surveillance capitalism work behind the scenes to determine everything about how we gain information, how we are tracked and targeted, how we consume and work as data subjects. In ultimate smooth flow, we’re left exposed, vulnerable to contextual distortions, losing the capacity for complex reasoning, choice, and nuance. In the contemporary post-truth state, the individual has been disregarded, alone in the crowd, subject to the perfect conditions for engineered bias and oppression.

Off time

Before total network saturation, we may have experienced a passive feeling of “getting lost” or “losing track of time” by reading a novel, or watching television or a film. We may have entered a smooth flowstate more actively in play: sports, gaming, dance, or music. By the mid-twentieth century, these were the kinds of activities that captured our focused attention, through deep engagement with designed narratives. These legacy forms evolved directly out of American capitalism and a very specific idea about productivity: the modern 40-hour work-week and its distinct division between routine labor and leisure. Focused attention from 9 to 5 at the factory, office, or school was offset by the modern construction of leisure time, designed to occur after school, during the weekend, on vacation: “off-time.”

A smooth, flowing experience of leisure required predictability. Narrative structures were known forms, and they came with precise expectations. The TV sitcom, the Hollywood movie, the romance novel, and the football game evolved into predictable formats, with fixed durations. So while the feeling of lost time and “losing oneself” was possible while watching a soap opera, this state of suspension was never totally controlled by the subject; it was contained within the parameters of the media itself. When the form was engaged, it came with the explicit knowledge that there would be a way to end the story—and return to work. Distinct, finite narratives were not a new idea. The self-contained segment, episode, issue, or article was based on a known publishing paradigm that evolved as technology afforded new capabilities for mass distribution. The delivery of information within a fixed format had accelerated since the development of moveable type, the ability to print onto a standard substrate, and the distribution of multiple copies in public. Printing and publishing spread as urban centers expanded, and “posting a notice” (with a known size or duration or frequency)—as a way to be “read in public,” in the form of a broadcast, a bulletin, a poster, a pamphlet, or the newspaper—allowed storytelling to evolve into fixed forms with predictable parameters that could be standardized and shared in public space.

Wasted time

Of course, not all leisure activity fit into these predictable forms of capitalist productivity in the twentieth-century. As an alternative to conventional work and play, a more extreme “numb state” of unending play or consumption was also possible. There were ways to pass time that didn’t fit into the modern work week, so they carried the stigma of vice, sin, taboo, and “wasted time.” Without a time limit or a way to end the story, alternative play could be stretched out. Time could be manipulated and controlled at the whim of the subject, leading to addictive behavior. Ultimate smooth flow engagement was first perfected in semi-public environments that were designed to capture compulsive, “off the clock” behavior—spaces like the video game arcade, the casino, the pornographic movie house, and the shopping mall—where unstructured time could be shared in a social way. Wasting time happened in these highly controlled spaces where perception could be slowed down and manipulated, distorted both by the designers of these spaces and the participants’ intense desire to stretch the engagement. Focusing on the casino and the relationship between the slot machine and player, Natasha Dow Schüll refers to this phenomenon as “machine zone,” a state of suspension where normative ideas about time, space, and social relations are completely distorted (Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas, Princeton University Press, 2012). Perhaps “machine zone” was already beginning to work on us in our living rooms with our burgeoning relationship to the television, but by the 1970s and 80s screens were spreading throughout the home and beyond, associated with new forms of watching and playing. The popularity of cable television in North America meant that ordinary people were spending more and more time in front of screens; around-the-clock delivery of never-ending content with the launch of ESPN in 1979, CNN in 1980, and MTV in 1981 ensured that our relationship to media was being normalized into a stretched-out 24/7 condition.

Pong (1971), one of the earliest arcade video games, was played like a simple game of table tennis. It would begin and end like a traditional match, but could be repeated without limit. It didn’t require a human partner, so the social friction of human contact and negotiation was removed. By introducing the video game console into the home, companies like Atari and Nintendo pumped machine zone directly into private domestic space alongside cable television, compounding this significant shift in our relationship to screens. By adding a new interface to the television and locating new kinds of screens in private space (the desktop computer), consumers were interacting more and more with less-structured, limitless forms of media. During this time, the relationship between player and digital material developed into something more private, controllable, and never-ending. Video games played at home normalized ultimate smooth flow; without the need for social context and regulated space, addictive play was transformed into a private activity. The new experience of ultimate smooth flow bridged the fixed, conventional forms of traditional media with what is now the familiar condition of contemporary network culture—the experience of stretchy time. Stretchy time is the continuous, ultimate smooth flow engagement with digital material on the network.

Network culture began to take shape at the same time that the video game entered the home. Stewart Brand’s The WELL began in 1985, and The Thing launched in 1991 as a networked space dedicated to artists. By 1993 web browsers could display both images and text, and their popularity exploded. But early online activity was less about flow and more about the old publishing paradigm of the fixed post—information that was organized around spatial metaphors, like threads, forums, mail, bulletin boards, and other “places” that delivered clear, fixed forms in a community environment (the posted announcement or reply, the email, the chat). As the world wide web expanded, the individual post continued to transition from physical space into a robust online medium, becoming the universal unit of early 2000s blogging and news. And the delivery of posted information in an organized, chronological form—the timeline—went on to become the basis of the feed.

Feeds and streams

Lately, feeds have swallowed the individual post. Since the introduction of Facebook’s wall in 2006, the iPhone in 2007, and Tumblr in 2008, endless feeds of conversations, updates, pictures, videos, music, and recommendations have become the primary way to engage with network culture. Feeds are faster now, controlled algorithmically, so the new publishing paradigm is a condition of constant changeability and performance. The massive accumulation of data for predictive markets, like targeted advertising, is more valuable than any individual post itself. The post—the individual, granular unit of the feed—is significant only in its accumulation. Because feeds are endless, and always changing, we remain engaged, even during sleep, conversation, and relationships. The draw of feeds, their ubiquity, and their ability to infuse any environment with a steady delivery of prompts and information—keeps us in a state of continuous ultimate smooth flow. There is no way to end the story. Our relationship to the production and consumption of information has become a frenzied, relentless condition that surpasses individual control. The post, now stripped of any ability to empower, barely registers. Instead, GAFA captures continuous flows of data in real time, tracking subjects through devices that are designed to keep us in a never-ending machine zone of engagement. The engine of surveillance capitalism is the algorithm, fine-tuned to deliver exactly what we need and want, keeping us entangled in the network with the promise of autonomy and an authentic sense of self. The more I engage with my feeds, the closer I’ll get to exactly who I am.

Image: Cyril Mottier

The feed as we know it is a product of late-stage capitalism, a non-stop accumulation of posts that becomes increasingly difficult to manage. With the enormity of content flowing into feeds, platforms began to use complex metrics to assign value to posts, as well as algorithmic sorting to increase this value at various levels: the individual post, the feed, and the user herself as laborer. All of this enabled data to be sold. What was once the relational condition of the individual post was now transformed into the economic condition of the algorithmically sorted feed, optimized by the platform for maximum performance and profit (at the expense of user experience). With the feed, users appear to profit in meaning, through the abundance of images and language—while at the same time accumulating unsustainable debt in data, control, and value.

Design plays a tremendous role in this cycle. Evidence of our addiction to flow is everywhere in user interface design today, from the spring-loaded pull-to-refresh Twitter feed to auto-play stories that have taken over most social media feeds. The “clicker game” is a perfect manifestation of machine zone interaction design taken to an extreme, delivering nothing but the pure act of clicking itself. Like an autonomous slot-machine, some clicker games continue to play on their own, even after the human player leaves (“idle games”). The popularity of clicker games is a symptom of the triumph of ultimate smooth flow addiction over the individual user’s sense of real time. Played endlessly, they seem to free the player from any narrative conventions or time limits at all; they are about the physical and emotional sensations of performing a single repetitive gesture, the pleasure of audio and visual feedback, and the reward of passive accumulation. In Cookie Clicker (2013) cookies “rain” from the sky but serve no function; the falling cookies feel like a feed but function like a backdrop, portraying progress and accumulation within a total void of meaning. Perhaps the labor of incremental clicking in these games could be understood as a struggle for meaning and value while entrenched in hyper-capitalism: the faster we perform, the less we gain. Walter Benjamin draws a striking connection between gambling and the assembly-line: “both activities involve a continuous series of repeating events, each having no connection with the preceding operation for the very reason that it is its exact repetition.” (Schüll, 2012).

Streams extend these ideas of repetition and stretchy time into something beyond the feed, a kind of flow that’s so smooth, and happening at such a high resolution, that the individual unit of the post (or cookie) is no longer relevant. In the continuous stream, game time is entirely given over to the sensation that the experience may stretch on forever. Streaming one’s labor on Twitch, a live video-streaming platform owned by Amazon, or YouTube, owned by Google, is the new success story, a fantastical, dreamy vision for an entire generation that’s been raised on an internet of centralized, corporate platforms. The idea that performative labor on the network can be influential—and profitable—drives streamers to broadcast gaming, ASMR services, unboxing, and scam baiting for days at a time, an intense kind of unstructured labor without any critical regard for the profitable structures that harvest the streamer’s resources (as well as their viewers). Of the million concurrent users active on Twitch at any one time, each plays a part in Amazon’s enormous ecosystem of commerce and data; streamers labor for “subs” (paid subscribers) only to hand over half of their revenue to Twitch. The pivot towards platform-based streaming is a stunning turn. In surveillance capitalism, the standard narrative form has expanded way beyond granular segments or units of engagement to become an endless landscape of continuously shared media—a dulling, textural condition where the “new boredom” can be experienced collectively forever, without regard for architecture, geography, or human endurance.

Perfect legibility

As more and more decisions are made within the context of algorithmically-controlled feeds and streams, user interface design is evolving to reinforce ultimate smooth flow with rewards that deliver the sensation of ease, productivity, and authentic choice. Fully engaged in flow, the subject is so captivated with stretchy time and its perfectly delivered activity that the weight and “burden” of the interface is relegated to peripheral vision; it seems to disappear. A commercial transaction is reduced to a single, effortless gesture on the phone (contactless payment). The fingerprint becomes the bridge of authenticity, a proof of identity that uses the body’s presence to complete the transaction with almost no effort—no swipe of a card, no verbal confirmation, no signature, no buttons to click. All friction has been removed; the reward is a pleasant sound that’s produced when the connection is made, which keeps the experience “flowing.” With the ability to capture identity with ultimate clarity (the fingerprint, Face ID, retinal recognition, etc.) now firmly established, other frictional aspects of the interface will eventually disappear entirely, making commercial transactions—and the surveillance it supports—much easier and faster across the network.

Source: Apple

The value of perfect legibility is evidenced in the secure fingerprint, facial recognition, an authentic identity; this kind of “reading” enables smooth transactions and engagements with the algorithms that mediate access to platform structures. The new publishing paradigm (feeds and streams) places a premium on perfect legibility; the ability for platform structures to scan, read, and discern creates an easily tracked ecosystem of inclusion (and exclusion) that’s crucial in order to sustain order and capital. Who has access? Who is profitable? Who belongs? To be read properly is to be given entry into the dream of perfect integration, to be accepted into Silicon Valley’s promise of fulfillment, privilege, and ultimate smooth flow. To resist legibility is to resist being a useful and attractive component to capital.

Interference

How might we interfere with ultimate smooth flow? Is it possible to occupy the feed without necessarily adhering to its values? Certain artists and writers disrupt the smoothness of the feed, resisting “perfect legibility” without total refutation of the network. Instead, they propose a more tenuous relationship to ultimate smooth flow, locating artistic practice just outside the stream. There’s precarity in this type of practice, a willingness to eschew traditional forms of success, and an openness to push through the feed “into a more chaotic realm of knowing and unknowing (Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, Duke University Press, 2011, p. 2).”

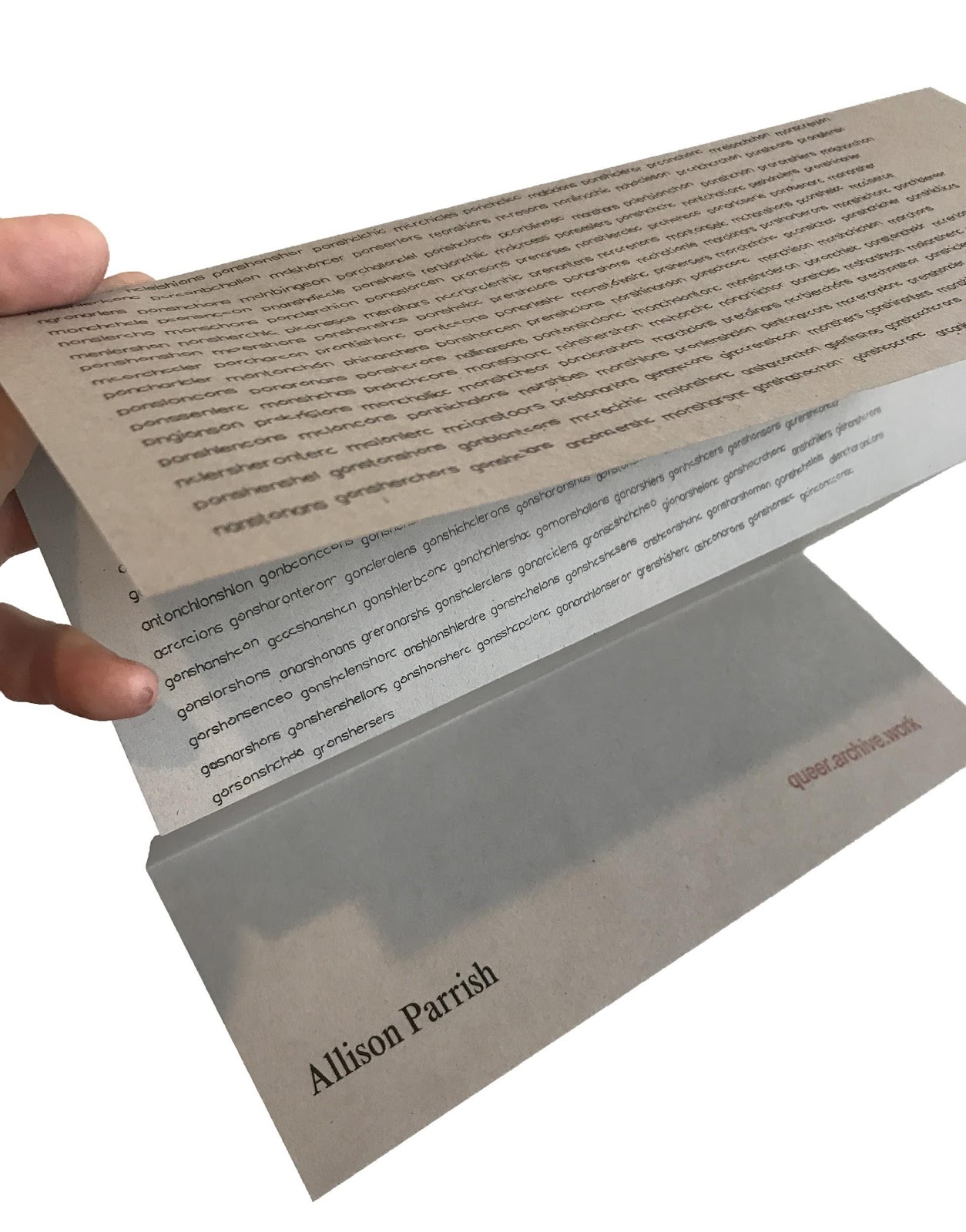

Allison Parrish in Queer.Archive.Work 1

Allison Parrish’s practice of computational poetry is an investigation of language at the outer edges of comprehension. She manipulates our expectation of ultimate smooth flow by using machine learning to create a “feed” of output that puts conventional understandings of language on hold. In Articulations (2018), Parrish creates poetry using “a computer program that extracts linguistic features from over two million lines of public domain poetry, then traces fluid paths between the lines based on their phonetic and syntactic similarities” (from her website). The result is a single 72-page work of poetry that somehow sounds like all poetry, precise and uncertain all at once. In Parrish’s work we can never “rest” in a passive position of ultimate smooth flow because the language constantly demands to be assembled into new forms of meaning and understanding; her poetry asks us to get to work:

...Behind the hill, behind the sky, behind

the hill, the house behind,—behind the house the house behind

the tall hill; for all behind the houses lay by my house and thy

house hangs all the world’s fate, on thy house and my house lies

half the world’s hate.

In thy house or my house is half the world’s hoard; drive the

herd towards the household, homeward drive the household

cattle, catch the child up to her heart. His eldest brother, who had

heard he heard her breath, he saw her hand, seize her hat, and

snarl her glossy hair. He sang: As once her hand I had, as once

her hand held mine; in the world His hands had made and his

harvest in her hands.

While we might get lost in the flowing output of her computational methodology, the jarring sense of uncanniness—language that is at once familiar and destabilizing at the same time—keeps us alert and aware of the non-human tools used in her practice. In The Wcnsske-Gonshanshcoma Reconstructions (2018) Parrish goes further, using machine learning interpolation to “travel” from one vectorized word to another; the result is a difficult one-thousand word poem that cannot be understood in any normative way. The language is dense, without syntax, and almost unpronounceable—providing a jarring audial experience that remains just beyond the limits of human understanding. Parrish asks us to work hard, and to look and listen to our feeds differently. Her poetry slows down the experience of machine output by providing friction where others look to smooth out language; she resists ultimate smooth flow by interfering with the promise of ease and perfect legibility in our contemporary feeds.

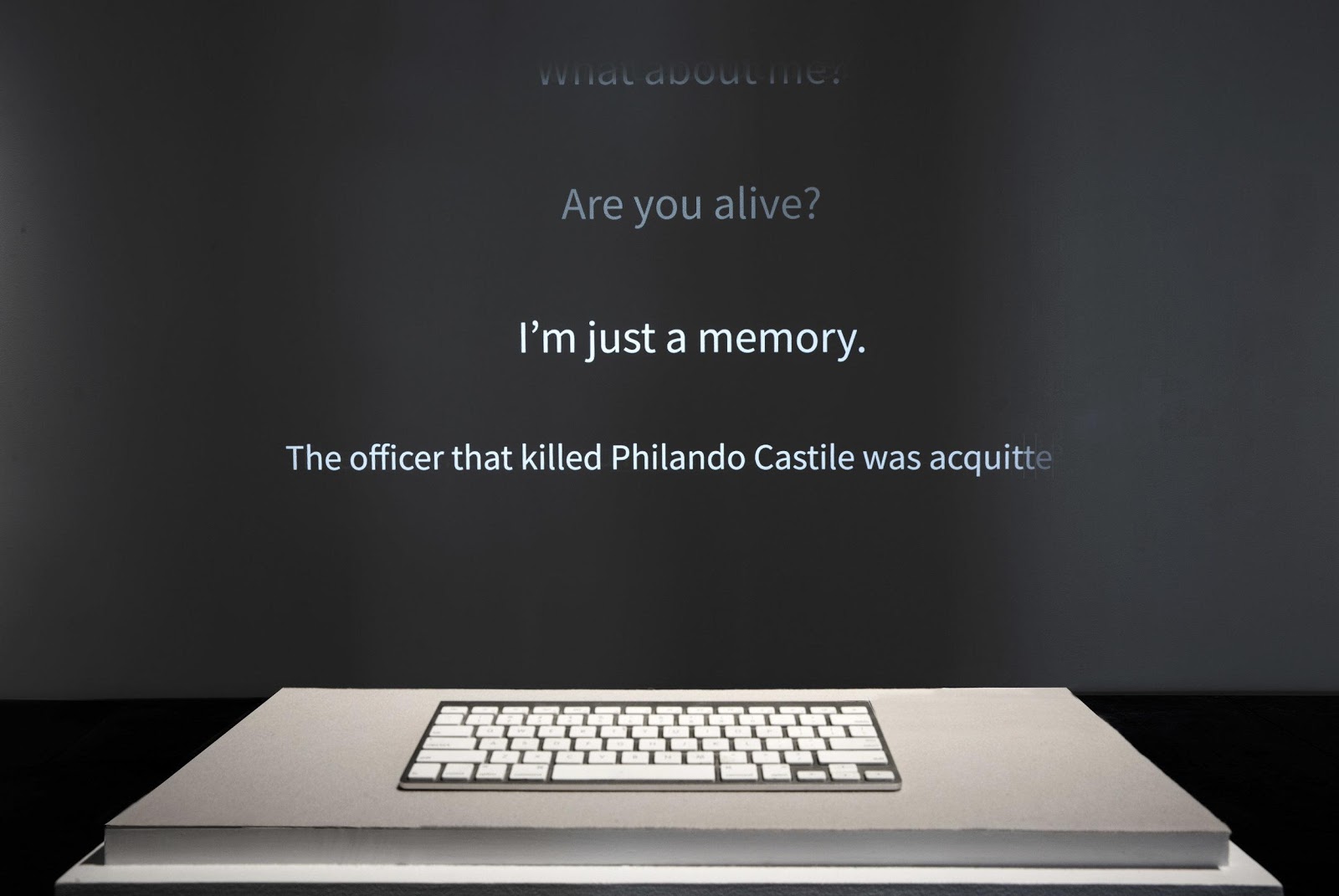

Image: American Artist

An enormous sense of urgent friction is also at work in the practice of American Artist, an artist who interferes with ultimate smooth flow by opening up and re-occupying a conventional understanding of contemporary media. In Sandy Speaks (2016), Artist builds a chatbot experience using AIML (Artificial Intelligence Markup Language), which can be programmed to simulate conversation with a human individual. The user engages in a conversation with “Sandy,” a chatbot that recalls Sandra Bland, the 28-year-old African-American woman who was found dead in her jail cell on July 13, 2015, three days after being arrested during a traffic stop. The chatbot talks about prison statistics, police brutality, Black Lives Matter, and the failure of surveillance. Artist writes that “creating a piece that simulates a conversation with a living individual recontextualizes the legacy of Sandra Bland.” By using the familiar environment of a chatbot interface, Artist disrupts the flow of natural language interface that we normally associate with bureaucracy: phone trees, online support bots, and call centers. Sandy Speaks opens up a moment of deep oppression by re-examining the supposed clarity and legibility of “facts” (mugshots, surveillance cam footage), allowing us to slow down the construction of this information and experience the failure of normative narratives. Artist’s chatbot puts that moment on pause, and asks us to imagine being addressed by the victim of police brutality herself. Artist writes that “beginning the conversation won’t be smooth, but rather awkward, because society is still learning the kinds of questions it should be asking and what level of transparency it is entitled to demand.”

Stretchy time keeps us drifting, dully focused on the stream in a continuous state of captivity. Perhaps the most radical use of the network isn’t art-based at all, but the ability of the President of the United States and other extremist figures to use the same platforms we use, to deliver misinformation. More than ever, we are susceptible to #fakenews, #deepfakes, and other kinds of information manufacturing that have yet to be imagined. How do we prepare for a future of uncertainty? It’s important to carefully examine our feeds and streams to find those voices who actively resist GAFA and the enabling structures of surveillance capitalism. Working against flow, their defining features might include non-linearity and a willingness to operate outside of legibility, to resist the “perfect read,” and to prioritize awkwardness over smoothness. Helping us to understand new ways of being in relation to technology are those who embrace failure and unproductivity in their practice, resisting the market’s promise of accomplishment and profit that accompanies ultimate smooth flow. Who speaks outside of normative positions of power within our platforms? It’s crucial that we look towards those who engage with network culture and politics to change the feedback loop. Whistleblowers, data preservationists, archivists, and artists maintain a different relationship with ultimate smooth flow, a tendency to disrupt and blur binary structures like public/private, lost/found, and static/active, especially LGBTQIA, Black, Indigenous, people of color, disabled people, immigrants, and others who speak from historically minoritized and marginalized positions. Those who have typically been left out of archives already provide friction, resistance, and interference by learning to operate in the margins of our feeds. Out of necessity, they shift our view away from the stream, training us towards the periphery. It’s there in the periphery, just beyond the edges of flow, that we’ll discover new modes of seeing, of relating, and of being.

April 2019