Publishing is political. Publishing can compel, persuade, inform, attract, confuse, script, or manipulate. Urgent acts of “making public” can mobilize communities and inspire change. In crisis, we see independent artists, community organizers, scholars, and activists collectively engaging with sophisticated modes of publishing to record and communicate in real time, while those in traditional positions of power use those same tools to engineer and control our defining narratives. It’s here that we can locate the enormous paradox of contemporary publishing: its potential to oppress as well as to empower.

From Facebook posts to presidential tweets, from dance-based memes to print-on-demand journals to mutual aid zines, stories are constructed and experiences shared across networks. How and why they reach us and why we’re compelled to trust them—or not—is crucial to any understanding of how publishing operates right now.

Publics consume and amplify, and sometimes resist and refuse, those defining narratives.

This syllabus focuses in particular on those queer strategies of resistance, refusal, and survival. As an overarching idea, urgentcraft explores the potential for radical publishing to gather and mobilize people around urgent artifacts and messages. As a syllabus, urgentcraft presents a range of artists, projects, texts, and concepts that foreground those strategies in recent history, as well as in contemporary independent publishing. As an expanding set of principles, urgentcraft identifies anti-racist ways of working in crisis, using art and design to fuel emancipatory projects and the movement towards liberation.

1

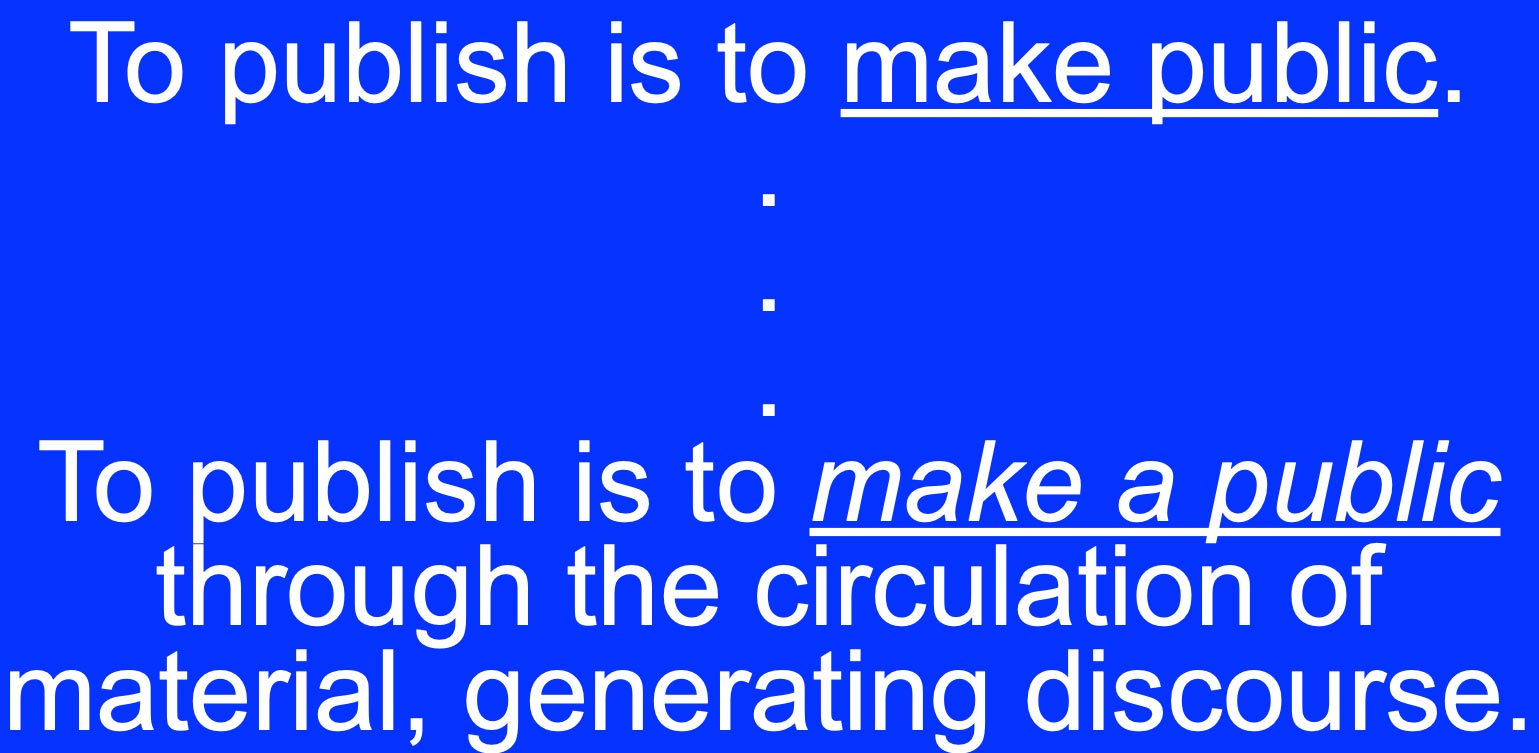

MAKING PUBLIC

Publishing is more than making a book. Publishing is larger than the artistic, commercial, and academic worlds that are commonly known as “the publishing industry.”

Today, publishing is personal and everyday. It’s the intimacy of direct communication over networks. It’s the fundamental act of making public.

Community bulletin board, Taiwan

I come back to the community bulletin board again and again as a basic and banal example of making public in physical space. Is this publishing? I propose that it is—that publishing is the act of selecting something to amplify, and posting that information in public to give it an audience.

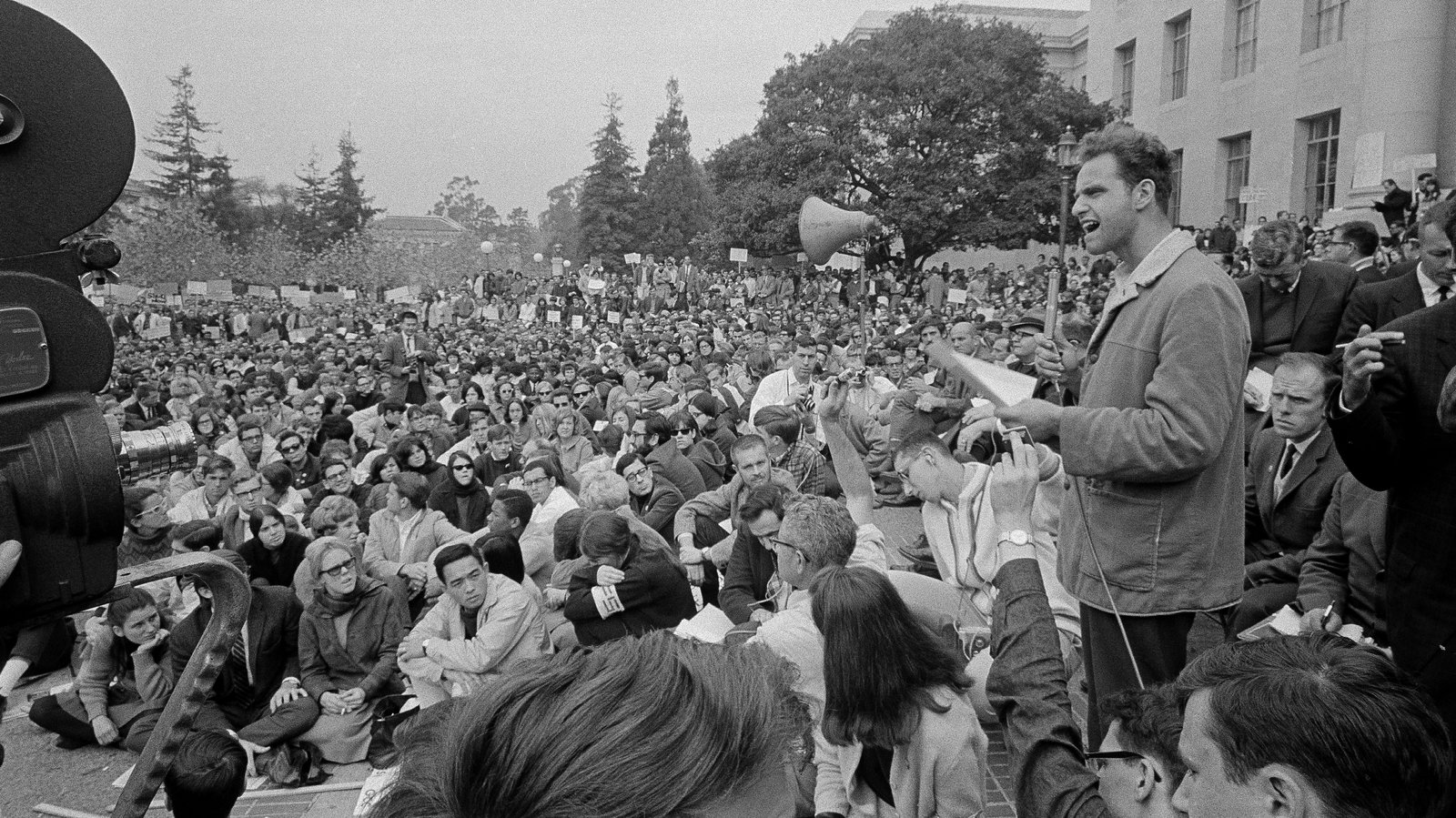

Mario Savio, leader of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, speaks to assembled students on the campus at the University of California, Berkeley, on Dec. 7, 1964 (source)

What about delivering a speech? Is this publishing? It’s certainly making public, but less about posting something and more about performing for a very specific audience. It brings up the idea of addressivity. In this notion of “the public,” everyone isn’t included—only those who have gathered in time and space to listen. This image asks us to look closely at what is meant by “public.” When we speak, who’s listening?

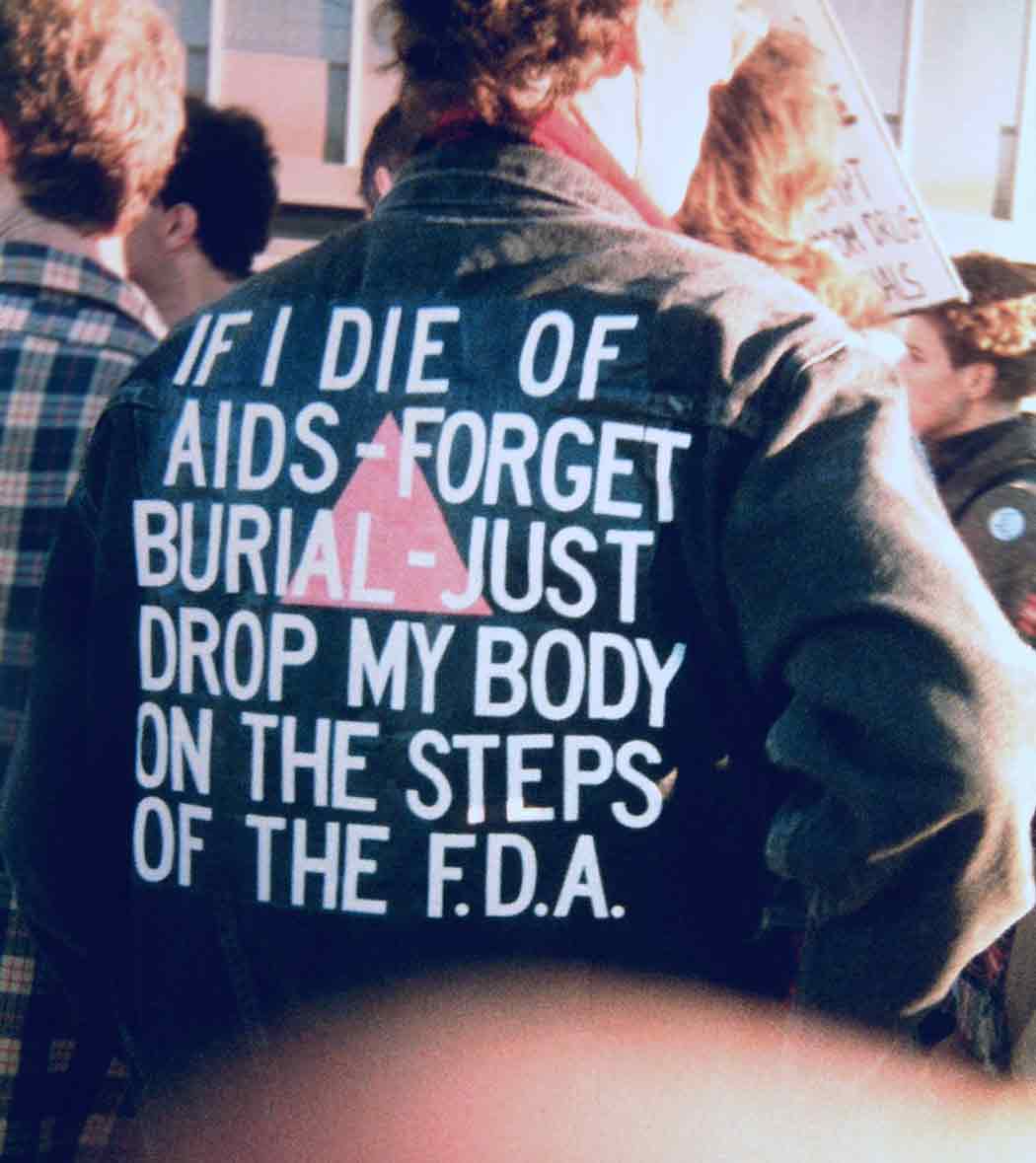

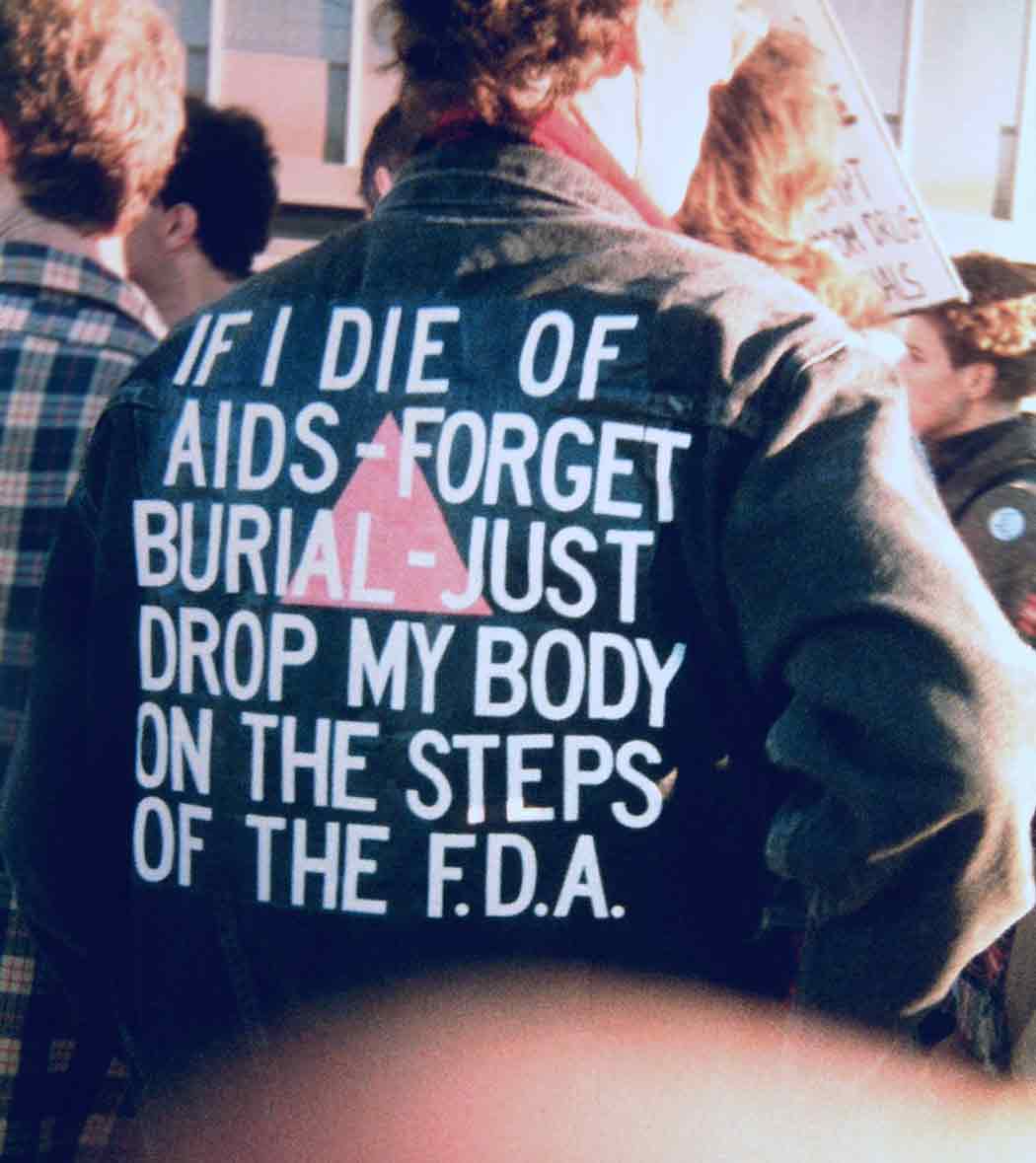

IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A., jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs. (source)

Is this jacket an act of publishing? More on the jacket below. This kind of making public interests me deeply.

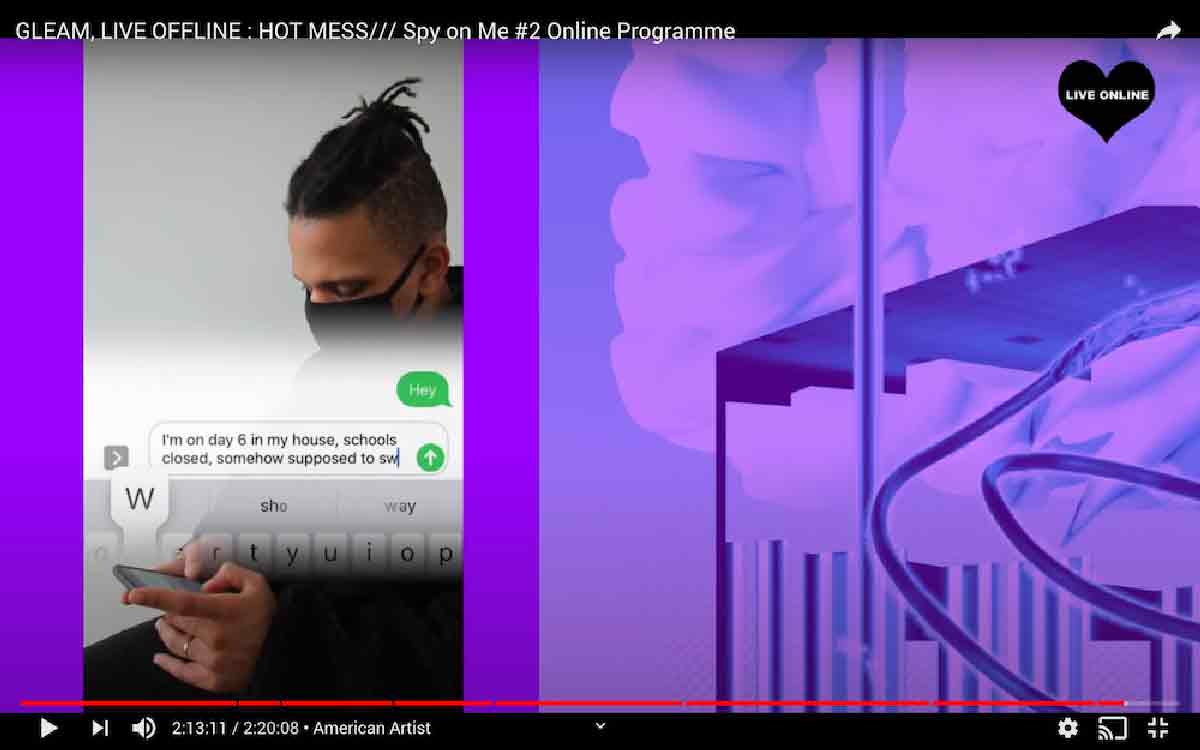

American Artist, streaming performance (March 20, 2020)

As do these newer forms of making public that are more temporal, durational, or ephemeral. All of these platforms are important to examine in the context of contemporary publishing. I love stretching the idea of publishing into these slippery spaces.

R.I.S.E. Indigenous (April 5, 2020)

These are forms that are super familiar to us now. Platforms that have become places for us to publish on a daily basis, cultivating vast audiences with direct engagement.

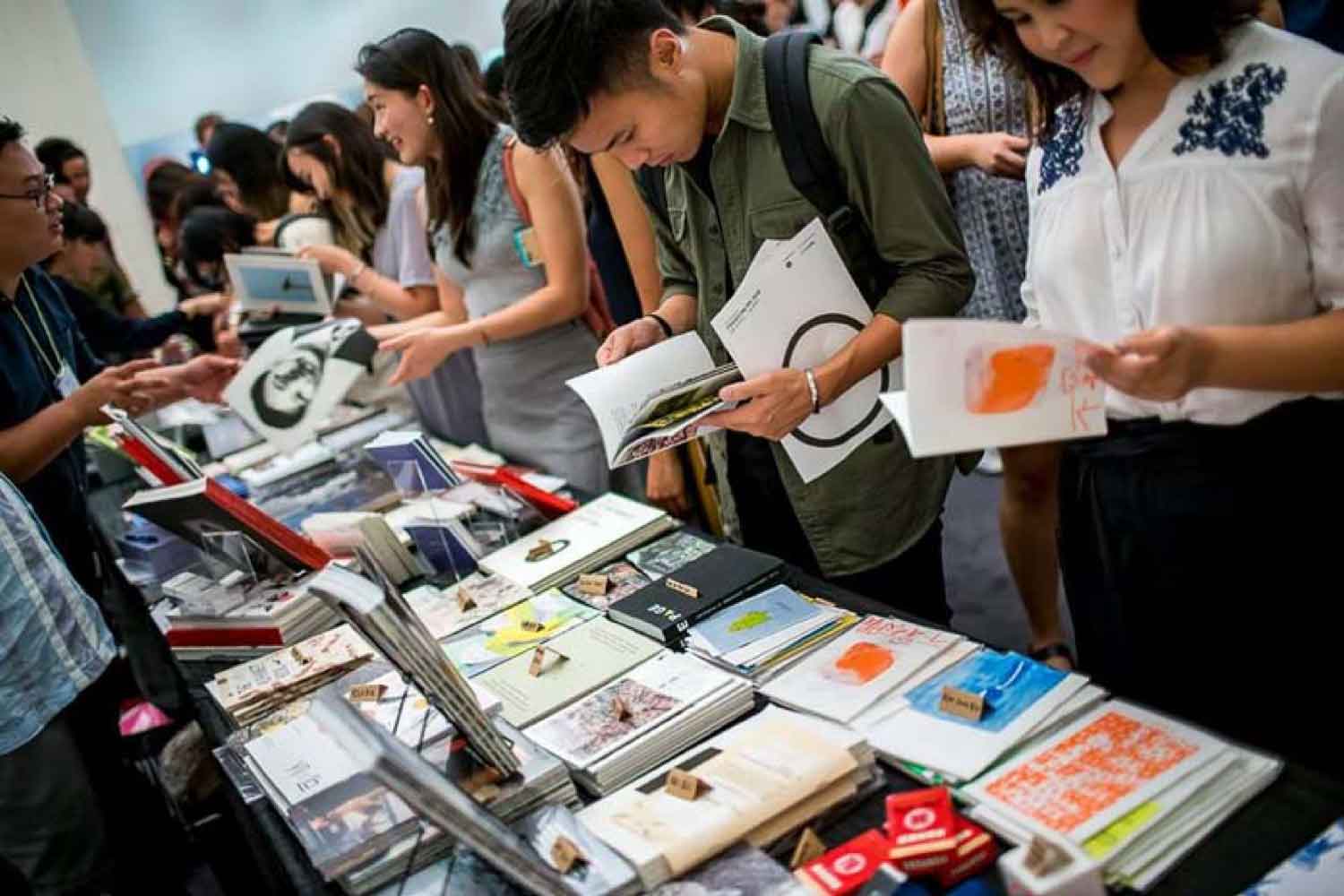

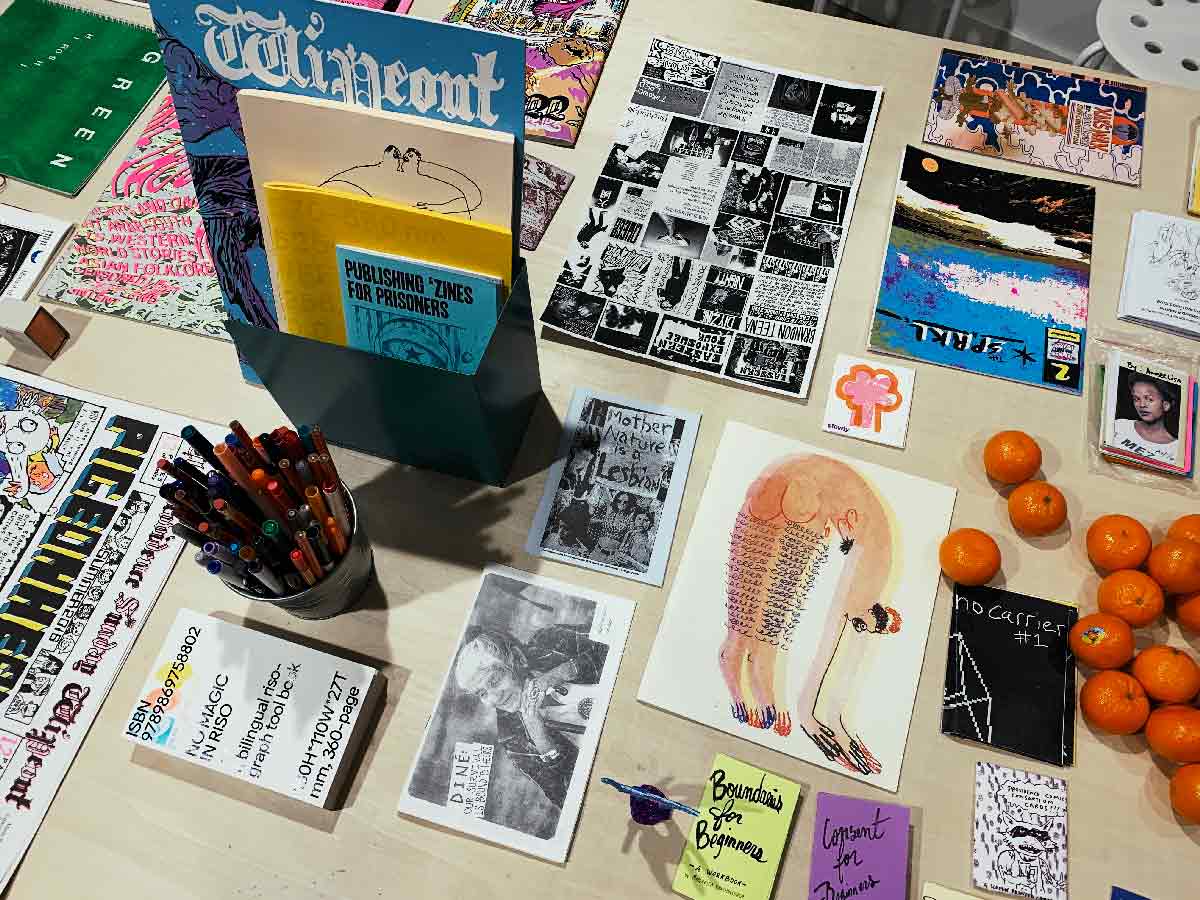

For the artist publisher, an ordinary table at an art book fair is yet another kind of platform, allowing the artist to be on one side and their public on the other. Direct engagement over the published material, in physical space.

2

GESTURES OF PUBLISHING

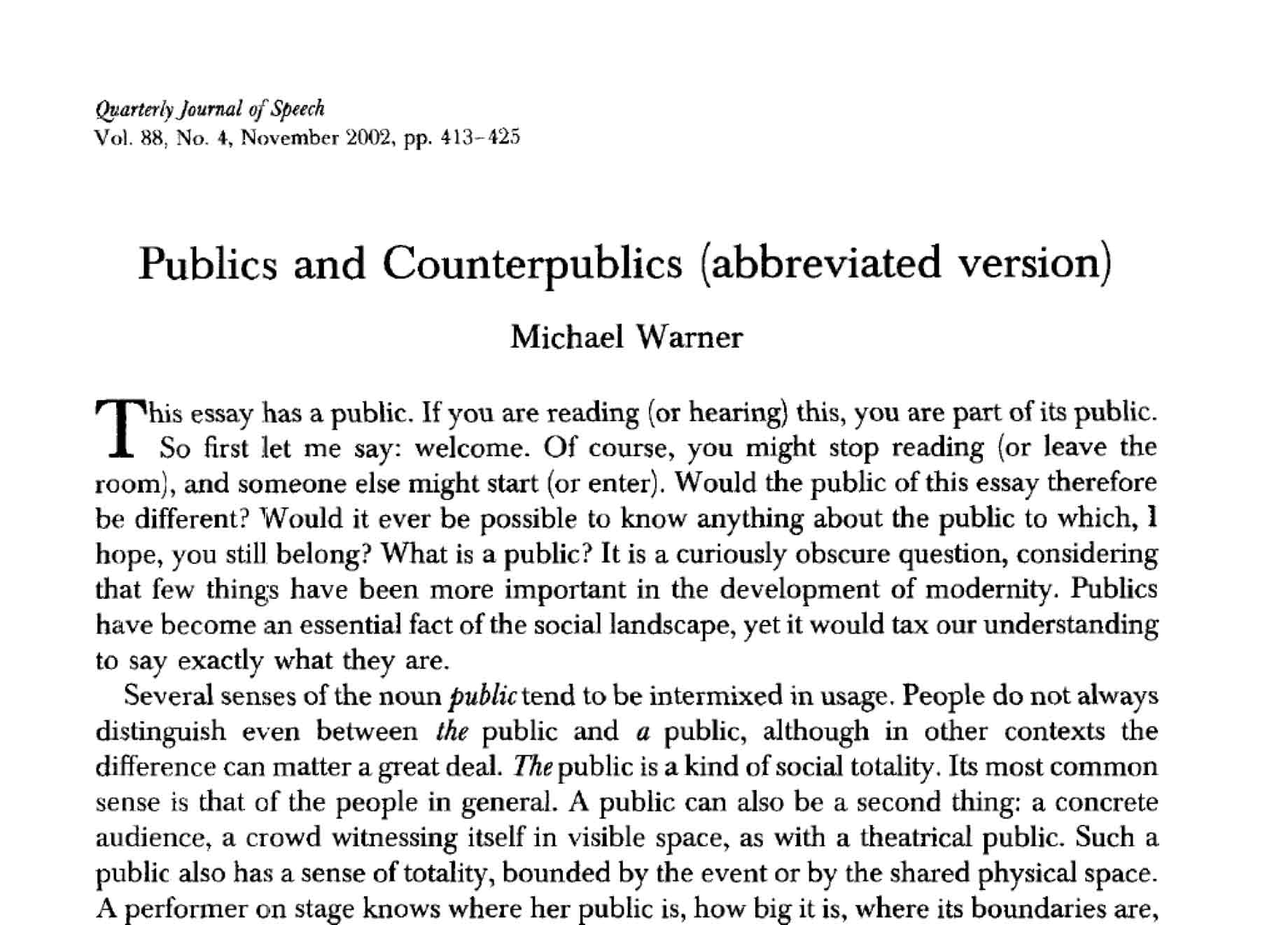

Michael Warner, “Publics and Counterpublics,” (2002) (PDF)

I’m borrowing these ideas from social theorist Michael Warner, who wrote about publics in his text “Publics and Counterpublics.” I come back to this dense reading again and again. When I discuss it with students I usually re-read it, and to try to get a little bit further with it each time.

In this text Warner makes distinctions between the public, or “everyone out there,” and a very specific public—say, those particular people who have intentionally gathered around to listen. In “Publics and Counterpublics” Warner gives us the concept of multiple publics.

Warner says that to publish is not just to “make public,” but to form “a public” through discourse—“the kind of public that comes into being only in relation to texts and their circulation.” A public gathers around the work as it travels, as it’s referenced and cited, and as it’s discussed. Only then has a public formed.

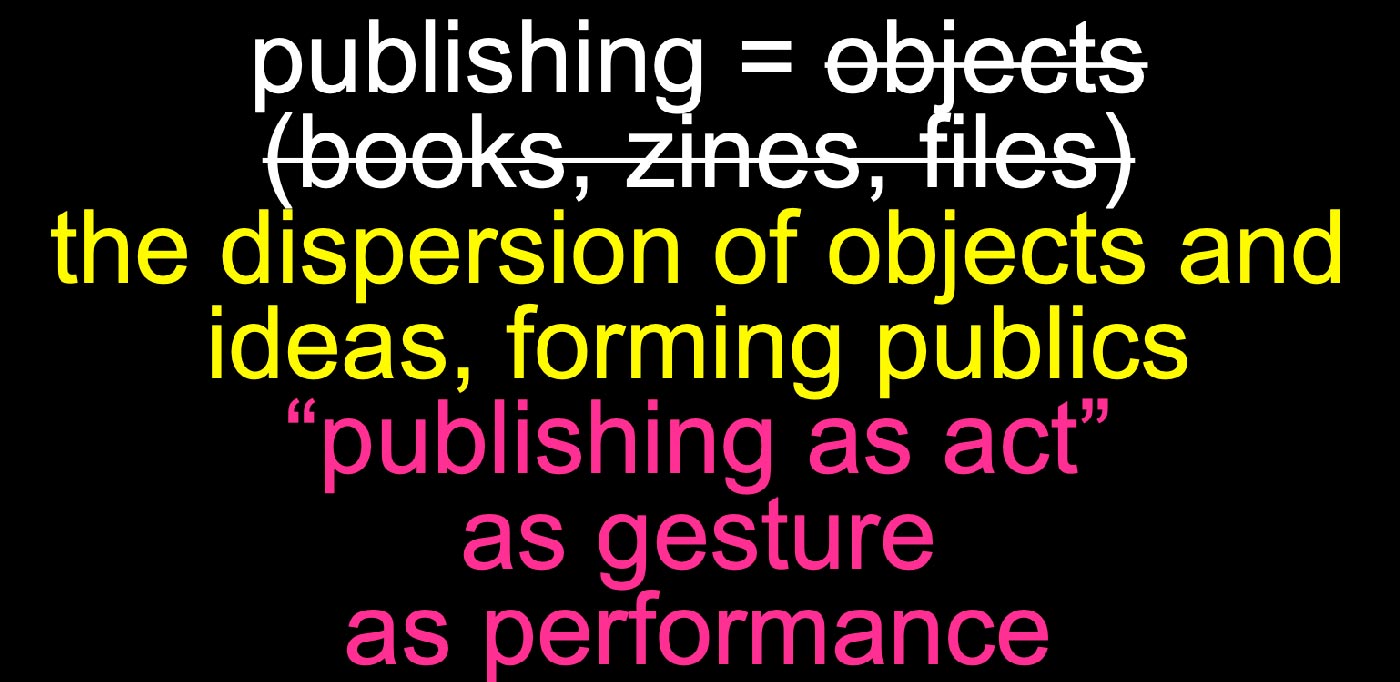

Previously, we may have thought about publishing as the production of objects: things that one makes, like books, zines, and digital files.

But publishing is less about the objects you make, and more about the actions you take. Your publics form around these actions, through the dispersion of material. Seth Price writes about this in “Dispersion.” As an act of “distribution, rather than production,” it’s easy to consider artistic publishing in these terms, as a gesture or performance.

This is why acts of performative publishing like live streaming or posting are intriguing: the act of accessing the work is an engagement with the gesture of publishing itself. In The Download, a series of commissioned works for Rhizome, artists created digital works of net art solely intended for download, contained entirely within ZIP files.

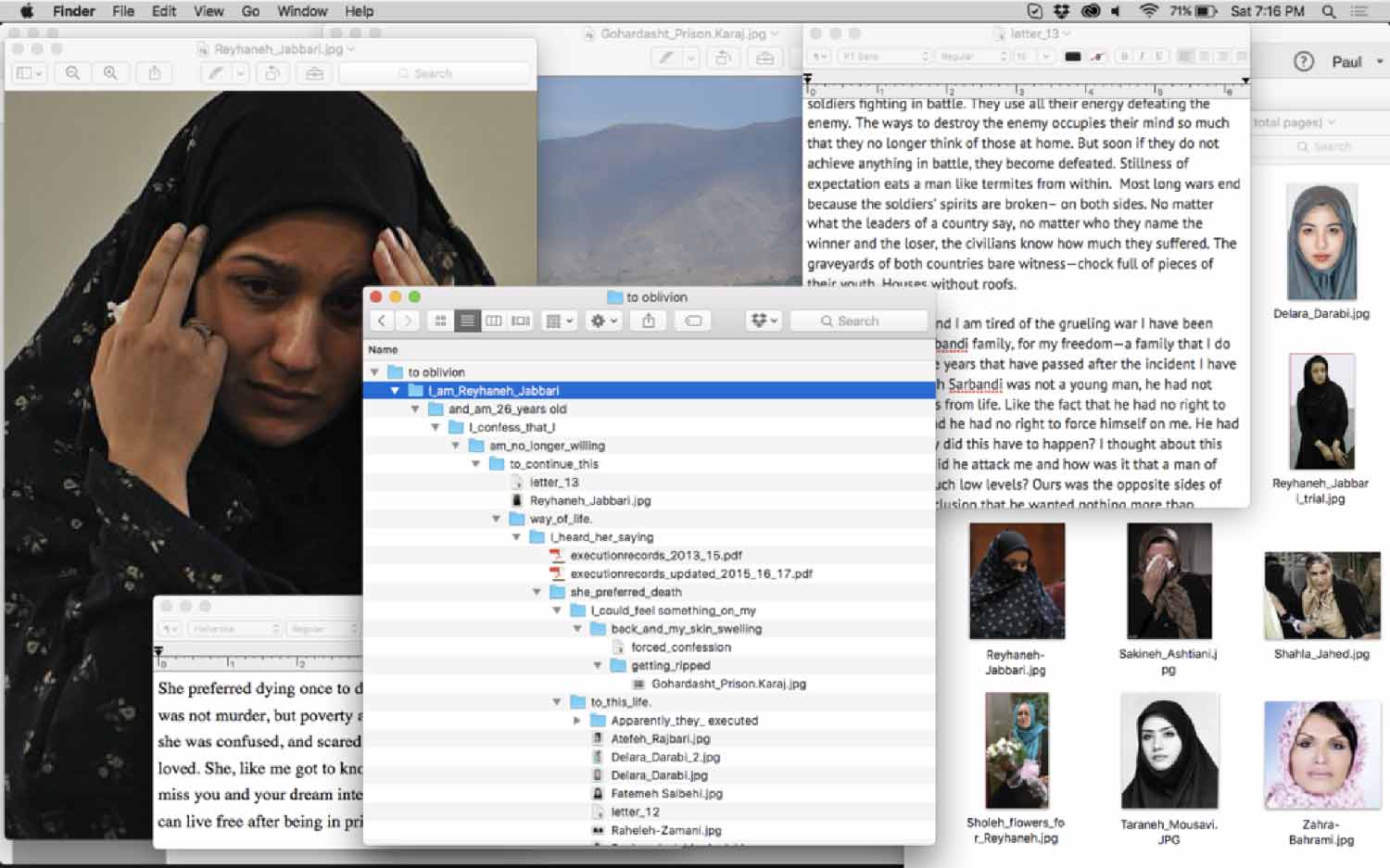

Sheida Soleimani, The Download #6, to oblivion.zip (2017)

In The Download, the act of publishing is located within the uploading and downloading of the files, the private performance of these files on a viewer’s desktop, and the circulation of those files on the network. Evidence of gestural acts and movements is contained in the language of the project itself: zipping, uploading, downloading, unzipping, expanding, etc.

Net Art Anthology (2016–19)

There’s an entire world of net art that approaches publishing in this way, centered on the digital files that circulate from server to server, device to device. Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology indexes the history of net art, and is a valuable resource for understanding how artists have worked on digital networks during the last forty years.

The Art Happens Here: Net Art Anthology (2019)

Net Art Anthology is documented online and in this beautiful book. It includes “The Post as Medium,” which traces a history of the post as a gesture of publishing.

3

POSTING

Posting is an essential act of publishing, perhaps the oldest. I’m referring to the act of posting a photo or tweet, or making a blog post. But if we consider a deeper history of the word post, there’s little information to be found.

We can try to trace a history of the word post within other words that contain the gesture of posting, like “poster.” The poster is a basic form that carries within it the act of displaying its contents on a vertical surface, usually in public space. The poster’s origins are thousands of years old, or even older, if we consider the very first marks made by humans on walls. Posting is a foundational gesture.

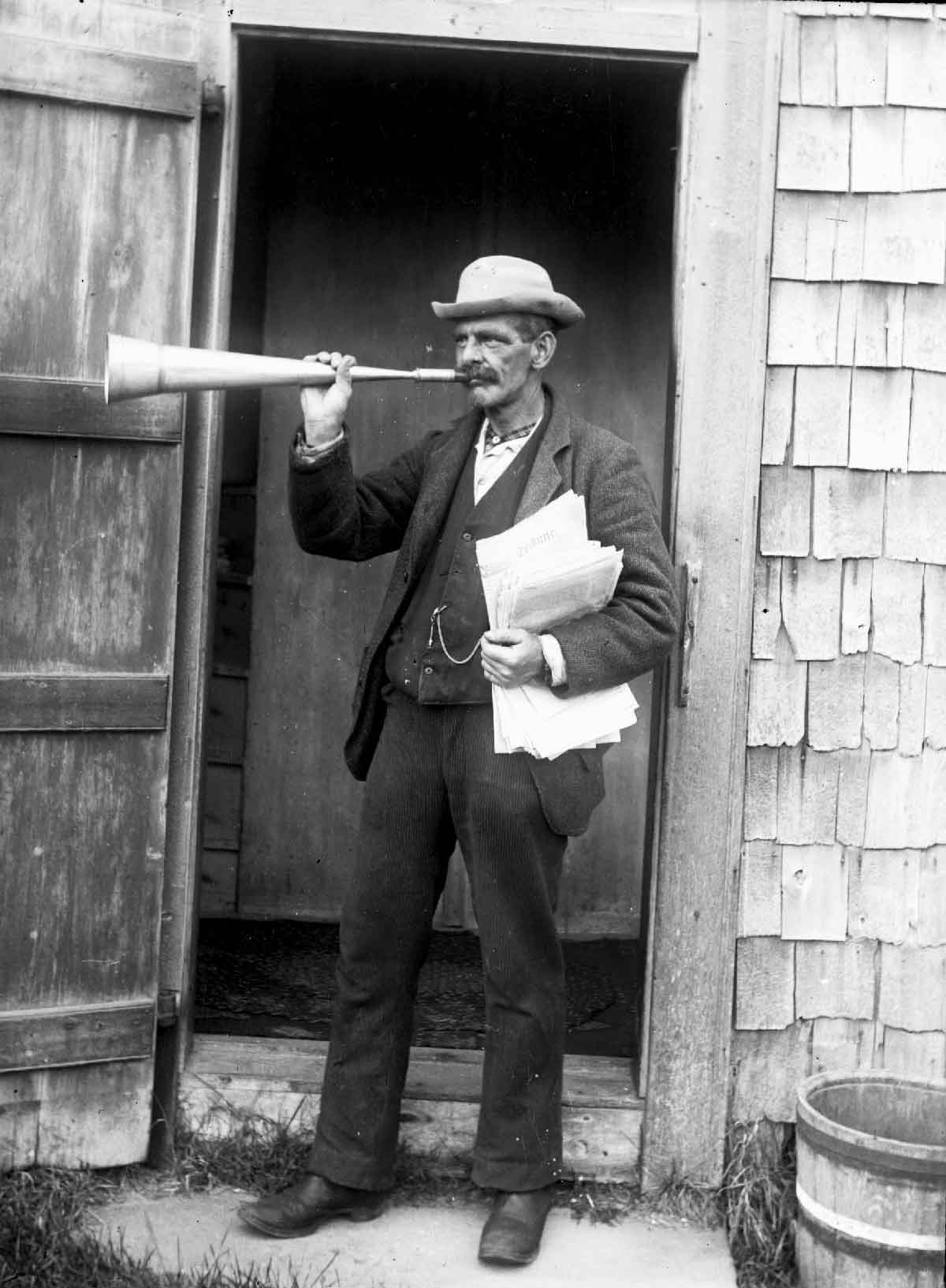

But what about English language expressions like “keep me posted,” or “post office,” or “the daily post?” Without sufficient scholarly research, it’s been suggested that “posting the news” comes from the figure of the town crier. He would read the news out loud at the center of town, for the benefit of a probably illiterate audience. When he was finished announcing the news, he would nail the paper to a door post as visible evidence of it having been heard, and so—the news was posted.

Jenny Holzer, Truisms (1977–79) (source)

There’s a rich history of artists who use this very basic gesture of posting in public space in order to announce something or give access to information, and directly engage with a more expanded audience. From Jenny Holzer’s Truisms in the 1970s,

Stephanie Syjuco, FREE TEXTS: An Open Source Reading Room (2012) (source)

to Stephanie Syjuco’s more recent use of the casual flier as a way to distribute URLs for downloading free PDFs,

Demian DinéYazhi´, falling is not falling but offering (2019) (source)

to Demian DinéYazhi´, who positioned these potent letterpress prints in a storefront window to face a statue of an indigenous figure in St. Louis, Missouri,

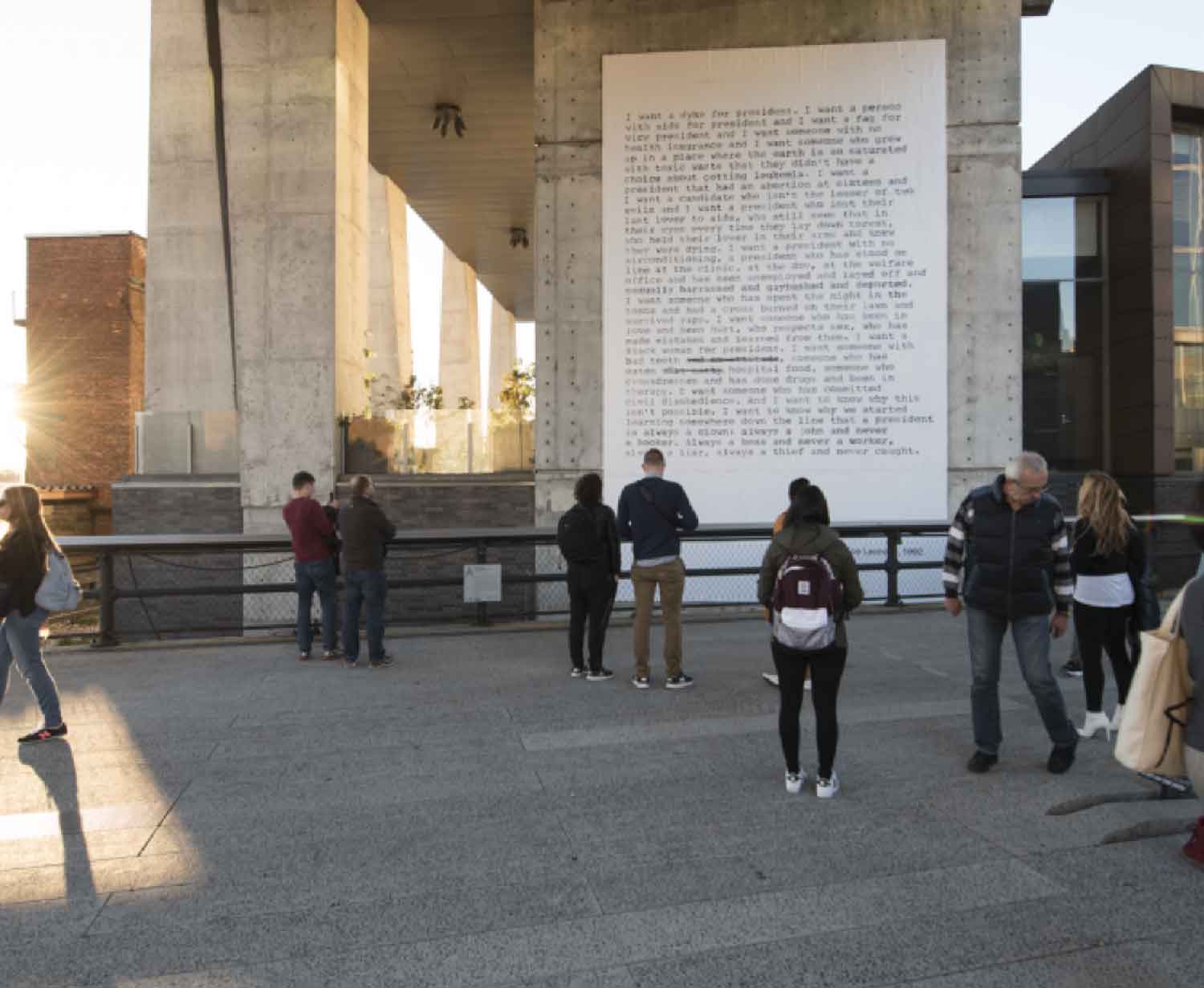

Zoe Leonard, I want a president (2016) (source)

and Zoe Leonard’s publishing of the statement “I want a dyke for president” early in the 1990s in support of the poet Eileen Myles, who was running for US president, and then again during the 2016 US presidential election, as a gigantic poster installed on the High Line in New York City,

Julia Weist, Reach (2015) (source)

to Julia Weist’s use of a billboard to amplify a made-up word—a fascinating, complicated project that’s worth digging into.

4

STACKING

Beyond the post, I propose a few other gestures of publishing, like stacking.

Like posting, stacking is basic. It brings to mind one of the most common ways to distribute printed material in public space: by using gravity. If something isn’t hanging up or posted on a wall, it’s probably sitting flat, stacked on a horizontal surface somewhere, like at a newsstand, or a bookstore, or an art book fair.

Library of Study

One may simply set up a table (or set down a blanket) as a way to display stacks of material in public. While posting doesn’t always invite a reciprocal gesture, stacking is a clear invitation to take. The new project Library of Study, located in Brooklyn, NY, curates books around an abolitionist theme and places them on a table in a public park, inviting discussion and borrowing.

Edson Chagas, Found not Taken, Venice Biennale (2013) (source)

Individual prints can be stacked on the floor, as Edson Chagas did at the Venice Biennale in 2013.

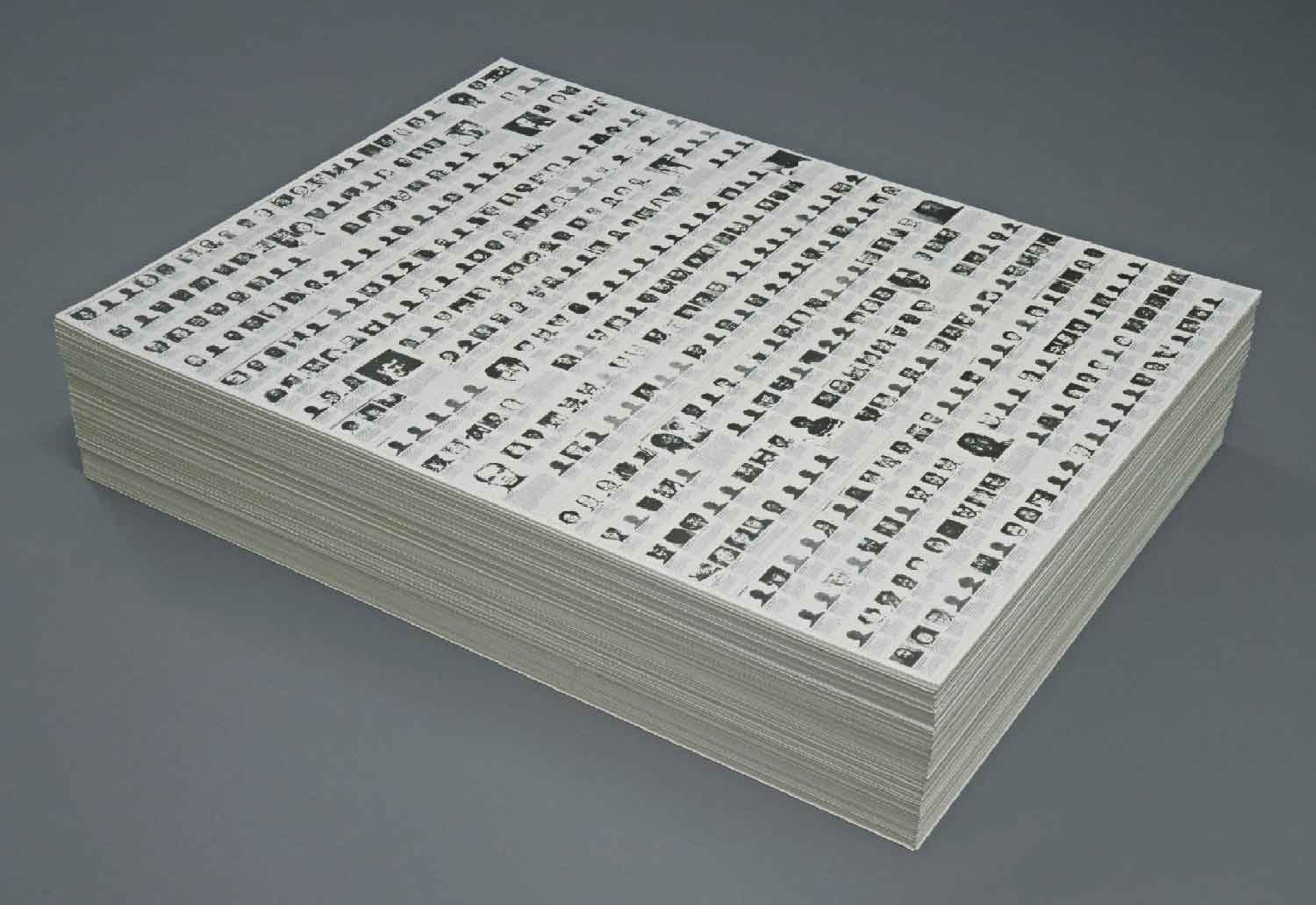

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Death by Gun), (1990) (source)

The artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres used the stack as a sculptural form in itself: the stack as medium.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres installation (source)

Felix’s stacks are unlimited; he wrote detailed instructions for keeping them constantly replenished. His stack works dismantle the monumentality of sculptural form; the artwork here is no longer a single, unique object, but rather an act of publishing that’s always disappearing and re-forming itself.

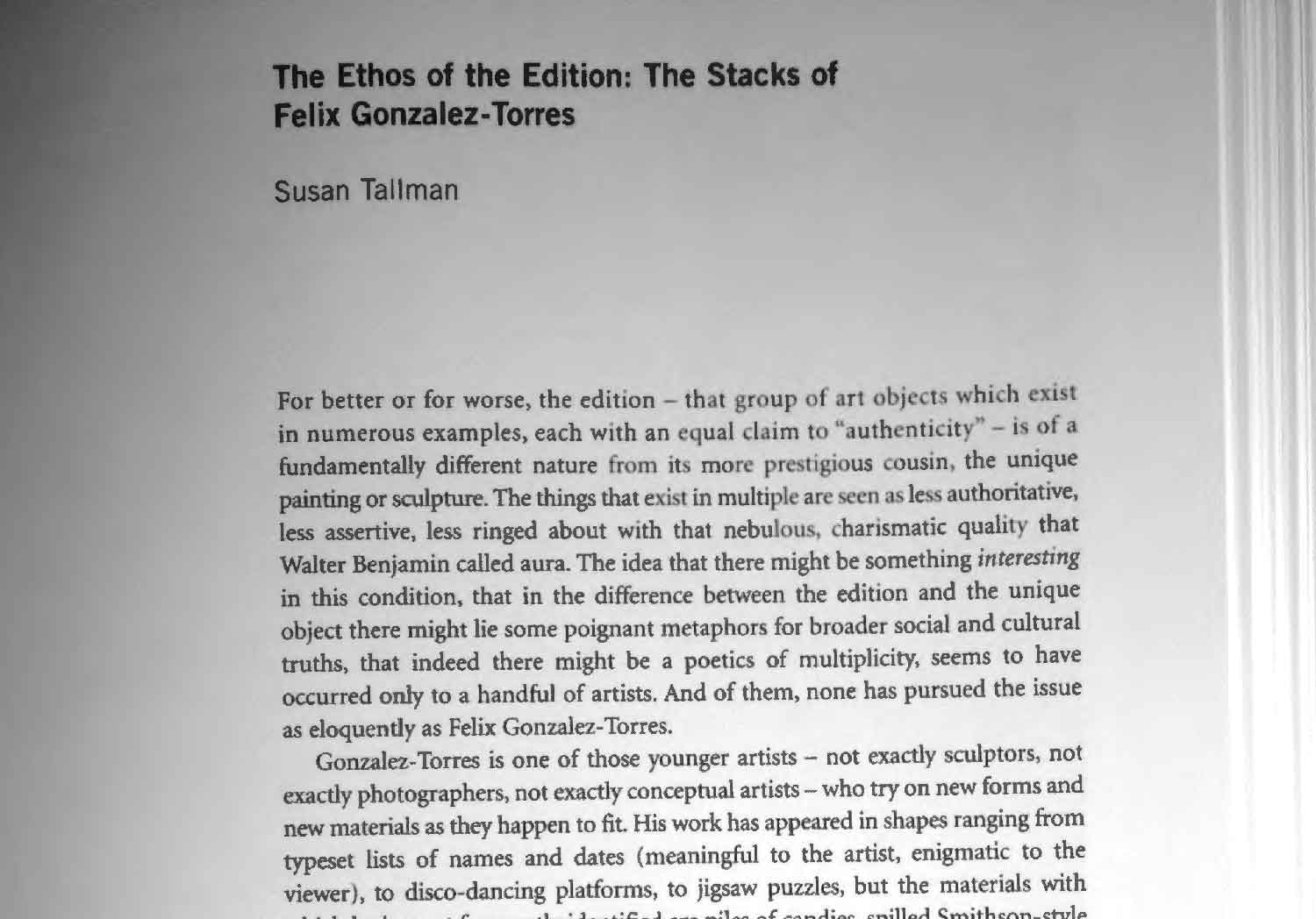

Susan Tallman, “The Ethos of the Edition: The Stacks of Felix Gonzalez-Torres” (1991) (PDF)

I’ve only found one good text on stacks: “The Ethos of the Edition,” by Susan Tallman, who writes specifically about the stacks of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and how he resists traditional notions of power by distributing his work in unlimited editions, more akin to a publishing model rather than an art market one.

5

DROPPING

flugblätter, or “flying leaves, leaflets” (source)

Dropping is another publishing gesture.

Dropping is much less common, but we know about it from images like these, which are associated with propaganda and the state. The idea is to force an act of publishing onto a specific territory.

Here, dropping is shown as a colonialist tactic—the author coming from above to impose a message, dropping it onto the land.

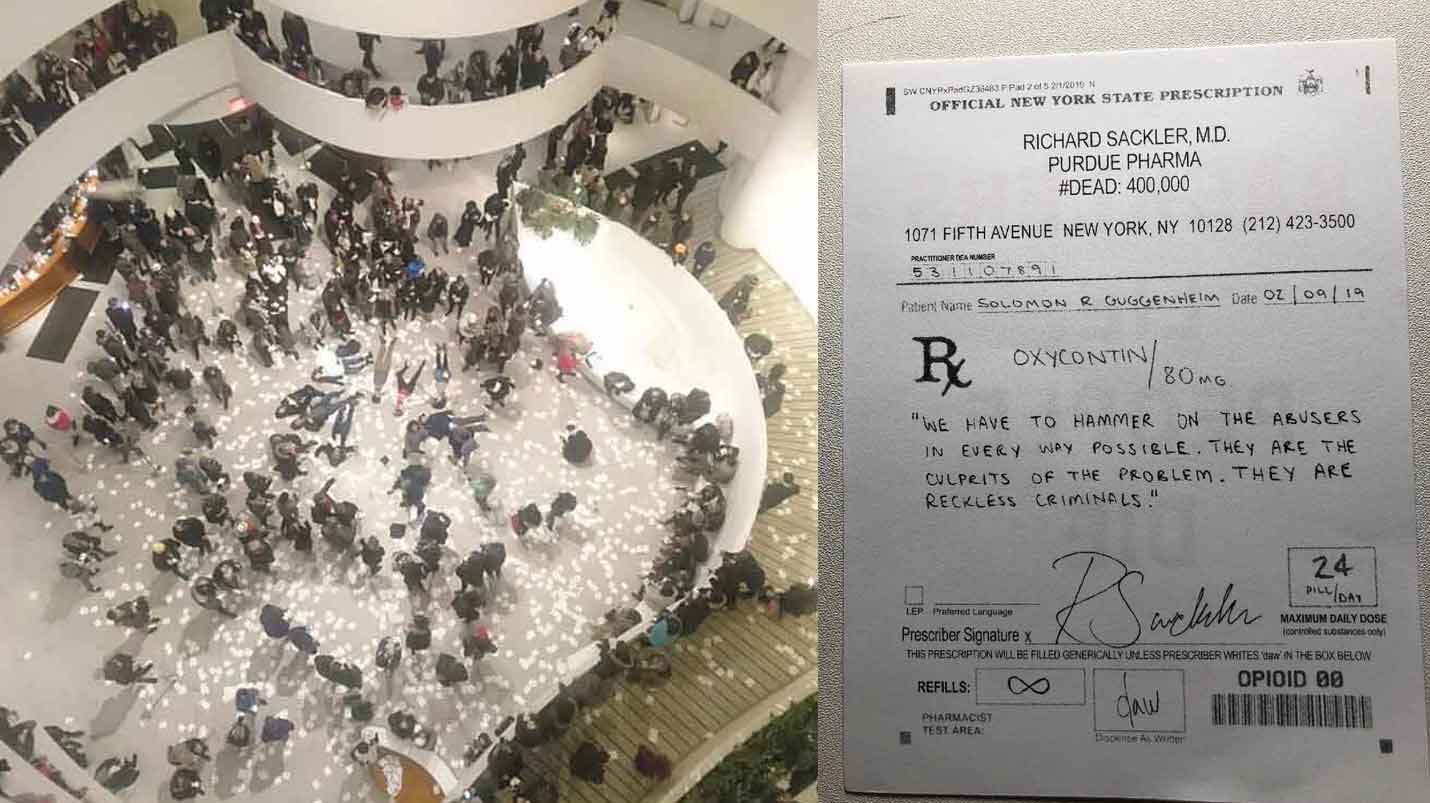

“Protesters Target Guggenheim Over Museum’s Ties To Family At Center Of Opioid Crisis,” Feb. 9, 2019 (source)

Dropping can also be used in protest, like here at the Guggenheim Museum on February 9, 2019. Protestors dropped leaflets designed to look like prescriptions, in response to the museum’s ties to the Sackler family and the OxyContin opioid crisis.

But dropping is also the language we use to talk about transferring digital files.

We know about this through the everyday act of publishing or sharing between devices, visualized as passing files through the air and dropping them into a specific location. As well as “dropping an album.” Dropping in this sense is associated with convenience and direct, immediate access.

Little Free Library

Using those same terms, this is dropping, too. Books are dropped off at a specific location, to be picked up in a direct way. This kind of dropping has an intimate feel to it, especially during socially distanced times, because of the physical act of touching materials and placing them in boxes in residential neighborhoods.

Anastasia Kubrak, Lost & Found Information, (2014) (source)

Anastasia Kubrak has a project that mixes together many of these ideas, where state-censored documents are printed and left at specially-marked drop points in the city of Moscow. The secret drop-off sites are identified by a graphic “X.”

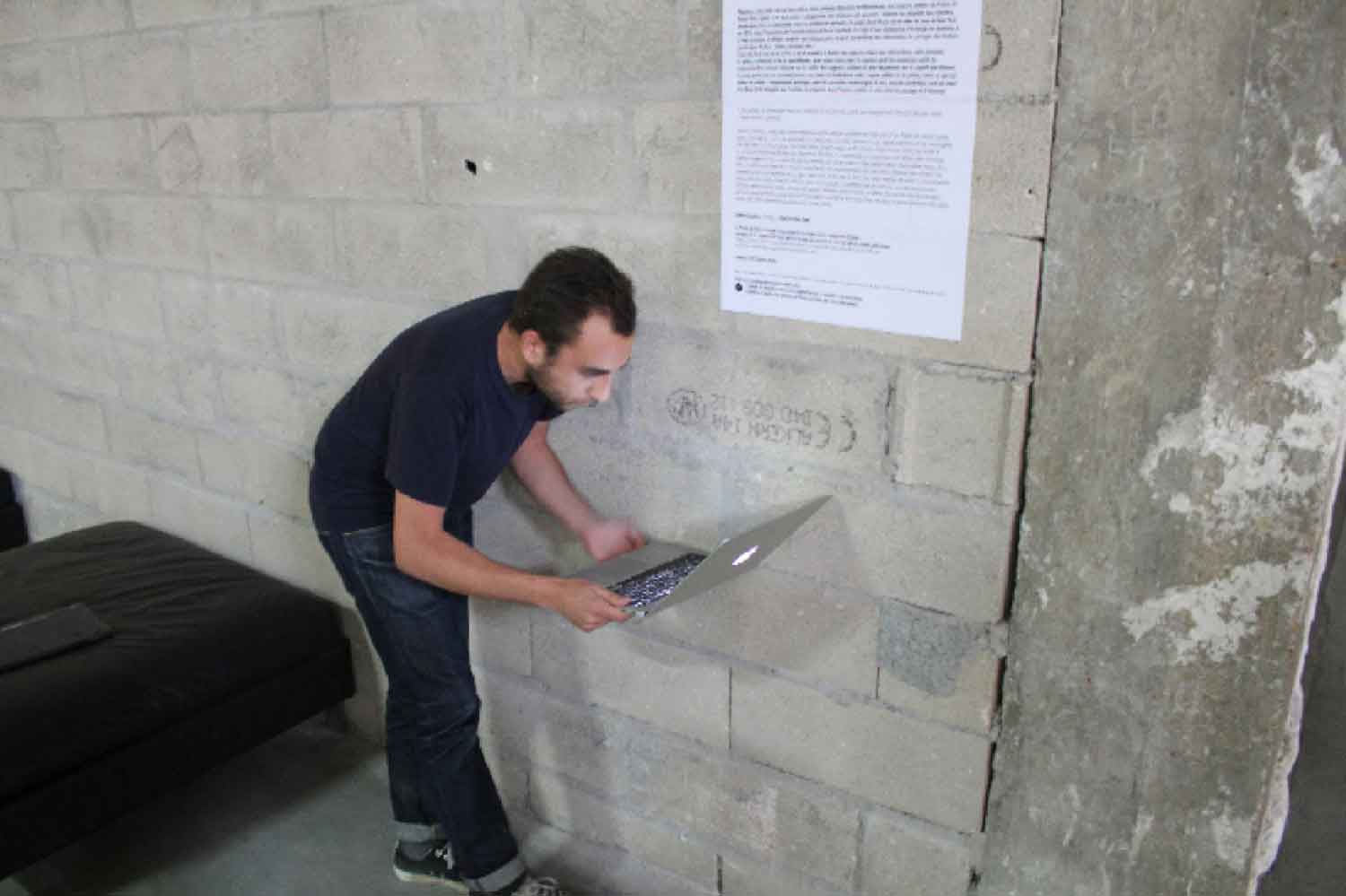

Aram Bartholl, Dead Drops (2010)

Aram Bartholl’s Dead Drops project is a vast network of USB drives (illicitly) embedded in architectural surfaces, usually located in public space. The project functions like an offline network for the distribution of digital material, totally independent from the internet, much like geocaching. I suspect that offline networks like this one will evolve into other forms, as specific formats like USB disappear.

6

FEEDS AND STREAMS

One more publishing gesture is streaming, or rather: feeds and streams.

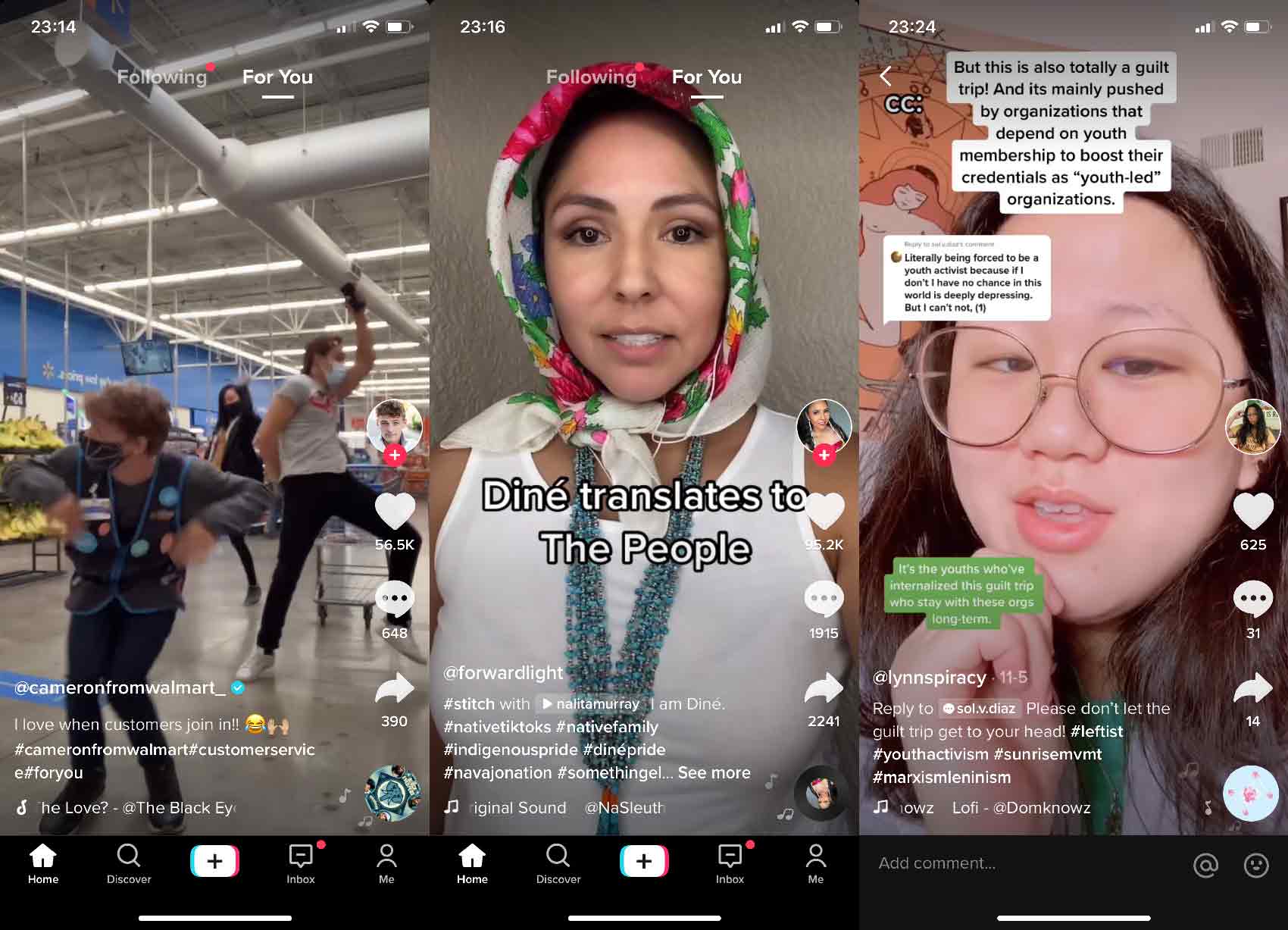

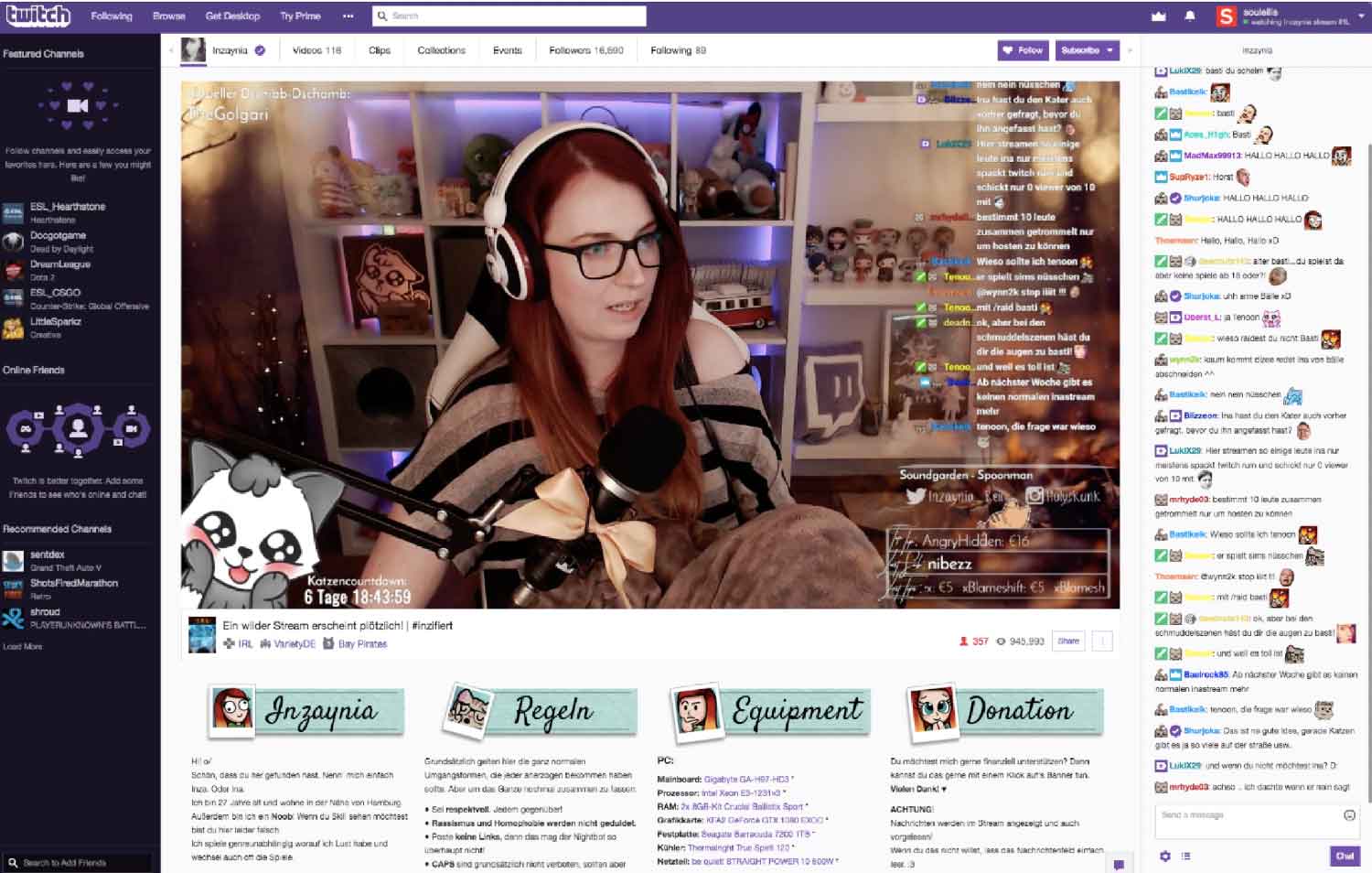

Individual posts are rarely encountered on their own; they accumulate into feeds. The feed is experienced as a never-ending flow of posts. I think this is one of the most significant ways to think about publishing today: the feeds we surround ourselves with, that we’re comforted by, and that we nurture and take care of. Our current notion of feeds began with the evolution of blogs in the late 90s, but exploded in popularity after the launch of the Facebook Wall in 2004, its News Feed in 2006, and the launches of Twitter in 2006, Tumblr in 2007, and Instagram in 2010.

“AOC Among Us FULL STREAM with Ilhan Omar and Twitch Streamers,” Oct 21, 2020 (source)

If accumulating posts are a feed, then the non-stop feed is a stream. Streaming is now an entire economy, with performers going live on YouTube and Twitch and Tiktok and sharing in those platforms’ profits. This is fundamentally different from the 20th-century model of broadcasting; platforms are easily accessible in exchange for data, which is extracted by enormous tech corporations for prediction and profit.

Hughes printing telegraph, 1870s (source)

Although the feed feels relatively new, it’s actually a product of the industrial revolution. I find the first references to feed as a flow of information in the early 1840s, around the invention of the telegraph. Photography also appears for the first time at exactly this moment. The feed continues to evolve as networked communication and information transmission advances through the 19th and 20th centuries (think: radio, television and the “live feed”).

But here’s how our feeds are quickly evolving today, in late-stage capitalism: the interface is dematerializing. We no longer see the feed visually or recognize it as an accumulation of posts. Rather, we feel it as an ambient presence. Consumer services like Alexa or Siri are still engineered to operate as a series of inquiries and responses that are “posted” back and forth. But the experience is much smoother than that. It’s no longer a bumpy interface of buttons and boxes, but of smooth, natural language.

7

ULTIMATE SMOOTH FLOW

With the dematerialization of the feed, I think the distinctions between what is or is not publishing are becoming increasingly blurry.

As we engage with non-stop streaming in a totalizing way, throughout all of our environments, we’re seeing this collision and collapse between publishing, digital networks, security, and surveillance.

This blurriness isn’t going anywhere. The ambiguity is becoming more and more ubiquitous and accepted. It’s a societal desire that we seem to have right now, to “arm” ourselves with these networks of seeing and listening, and the ideologies of profit and power that go along with this feeling of protection.

It’s crucial that we try to understand how this works, that we become aware of, investigate, and question the politics of our platforms. How the same streaming, always-on platforms that enable us to publish and communicate and entertain and protect and isolate ourselves—

are also the same platforms used by capitalism to profit and to persist, and by state institutions to surveil, to minoritize, and to criminalize.

It’s the ultimate smooth flow of algorithmic interfaces that know us and envelope us now that I’m most concerned about. Not because I don’t enjoy them—but because I do. As designers, we find ourselves in a very particular contradiction here. How do we participate in this? How do we teach design within this framework? How do we continue to design these most perfect interfaces, knowing what we do?

“The Tenants Fighting Back Against Facial Recognition Technology” (May 7, 2019) (source)

These are questions for each of us to wrestle with—as students, as working designers, as anyone invested in how design functions in our political state right now.

8

RESISTING THE SMOOTHNESS OF DESIGN PERFECTION

My own response to these questions takes the form of a demand: resist the smoothness of design perfection. I make this demand of myself and I ask it of students when I teach. This form of resistance means always questioning. More than questioning, it means committing to a deep examination of the less visible ideologies that lurk behind the design products that govern how we live and communicate.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, streamed live on July 9, 2020 (source)

In July 2020, I was able to tune into a talk by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, who discussed the beauty of shared practice over individual roles. Since then, I’ve been thinking about what this might mean specifically in the context of art and design schools. Those who were educated in mainstream art and design programs tend to continue to teach as they were taught, making it difficult to disrupt normative narratives around art and design.

Michael Rock, “Designer as Author” (1996) (source)

The institutions that pay us to teach today are built upon traditional neo-liberal values that prioritize individual expression and independence as transformative powers. We’re encouraged to teach the values that naturally go along with the successful figure of the artist as author or entrepreneur: ambition, competition, perfection, profit, ownership, self-sufficiency, and domination.

RISD’s call for “radical imagination” within its COVID-19 remote learning announcement, March 15, 2020 (source)

Because of how deeply these values are embedded within our institutions, it sometimes feels like we have no choice but to teach them. These values perpetuate the promise of professional success—an expectation that depends upon everyone driving towards the same destination: the credential. The credential is a degree, like a BFA or an MFA or a PhD, and the privilege and power granted by that degree: not only to participate in capitalism, but to accelerate within it and reproduce its violence.

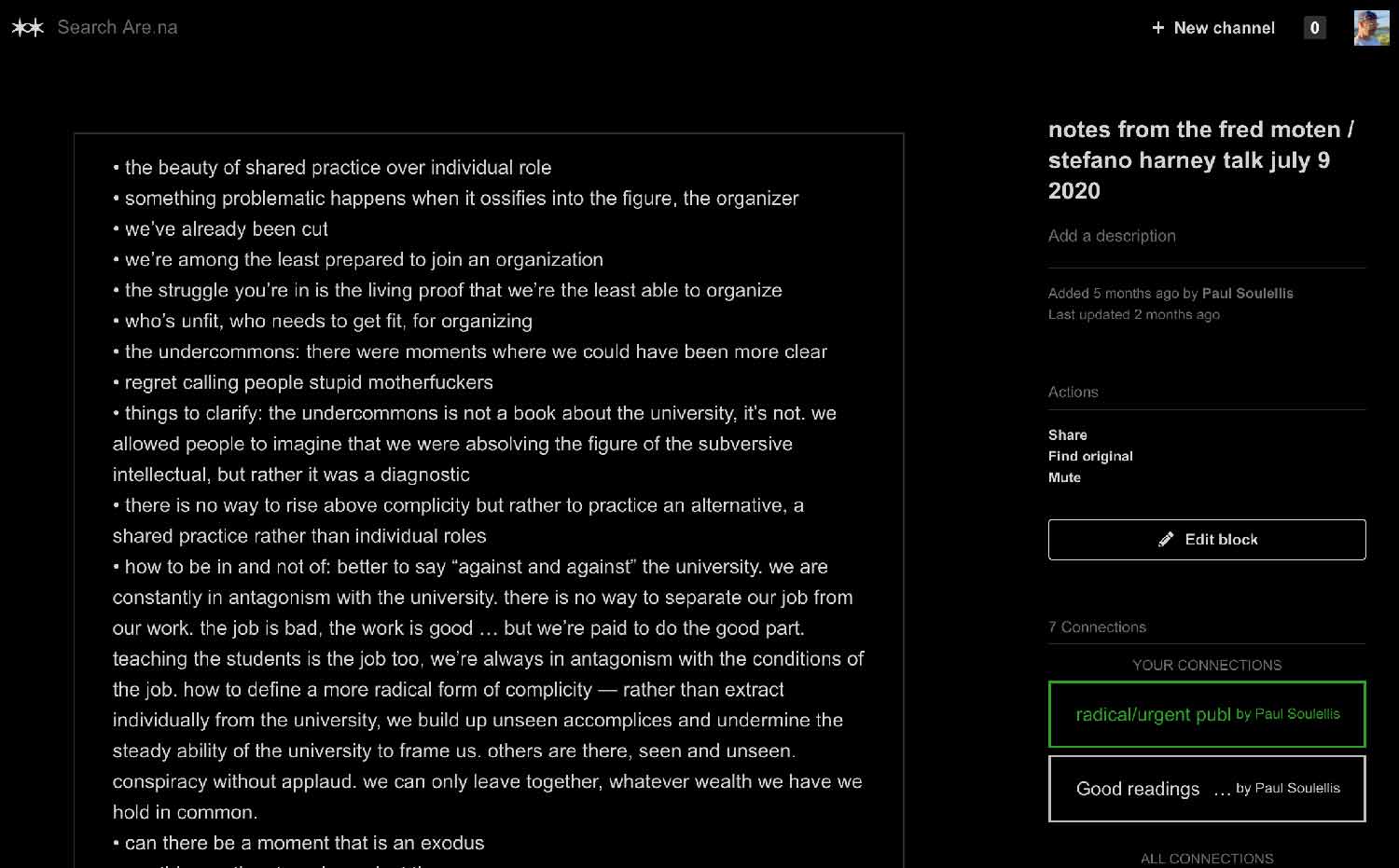

Notes from talk by Fred Moten & Stefano Harney, July 9, 2020 (source)

In our teaching, we prioritize exceptionalism as the most important value inherent in the student’s education, because the extractive practices of the art and design worlds require it. Students learn (and educators teach) that to be successful is to be sovereign and “better than:” a supreme, independent power without any need to depend upon anyone or anything, be it kin, or community, or state—unless it’s for profit.

9

SHARED PRACTICE

Instead, Dr. Moten asks, what would it look like to teach “the shared practice of fulfilling needs together as a kind of wealth—distinguishing and cultivating the wealth of our needs, rather than imagining that it’s possible to eliminate them.” This question resonates deeply with me right now, and it challenges me to pivot my own practice away from the institution: towards collective work, radical un-learning, the redistribution of resources, and communal care. From my work → to our work.

10

URGENT ARTIFACTS

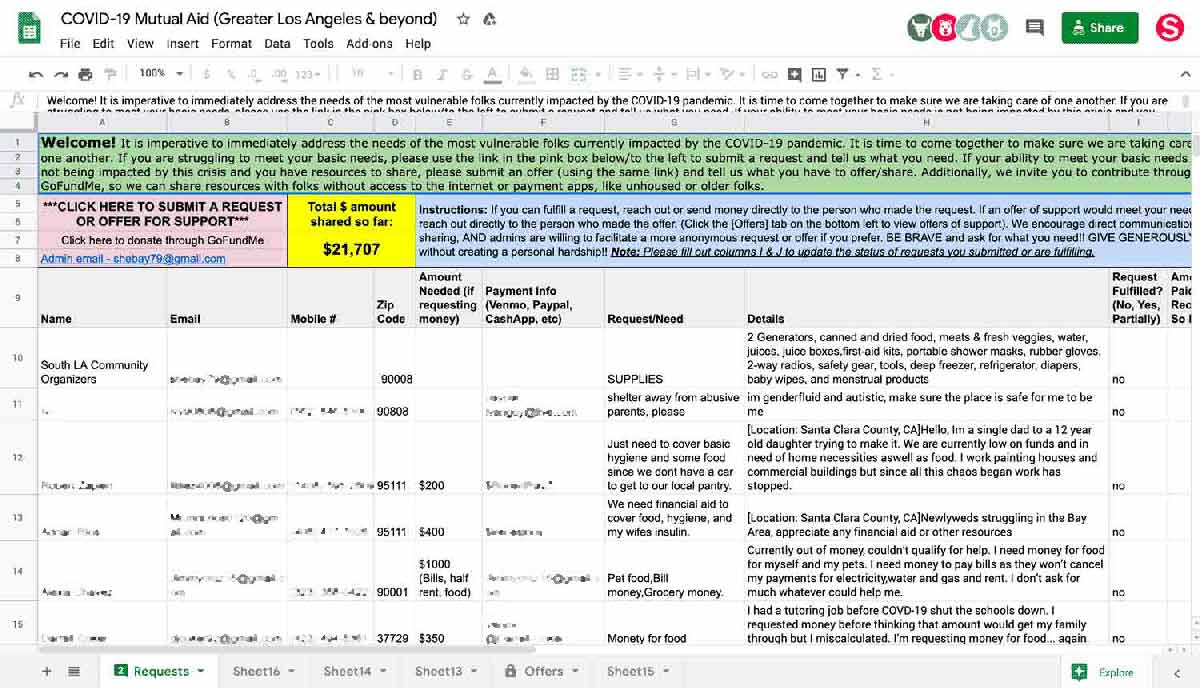

COVID-19 Mutual Aid (Greater Los Angeles and beyond), Google Doc, March 2020 (source)

When I look back at the urgent artifacts produced in 2020, during times of such crisis, so much of their power operates in this realm of shared practice. These are artifacts that step away from individual authorship, towards something larger—collective, cooperative works emerging from the shared wealth of needs.

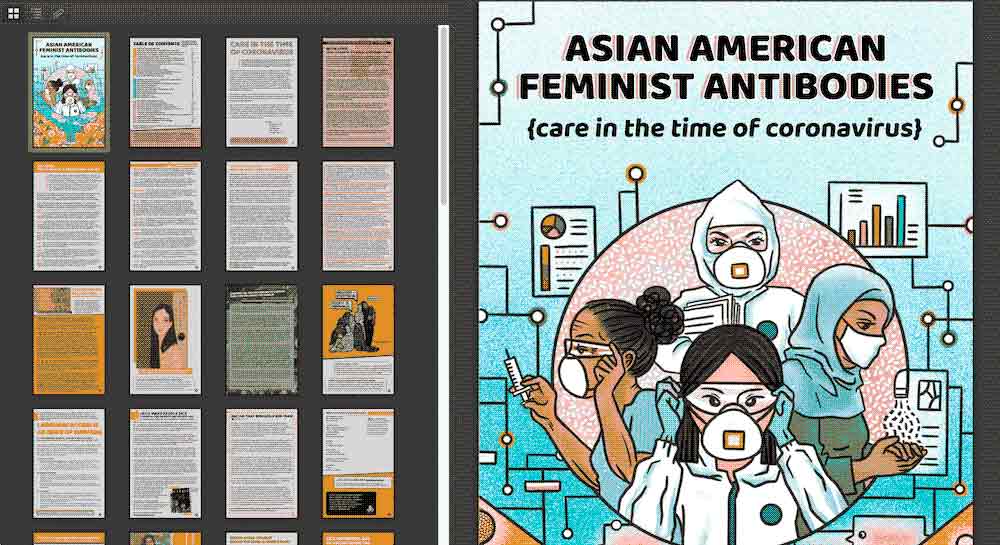

Asian American Feminist Antibodies {care in the time of coronavirus}, Asian American Feminist Collective, zine (2020) (source)

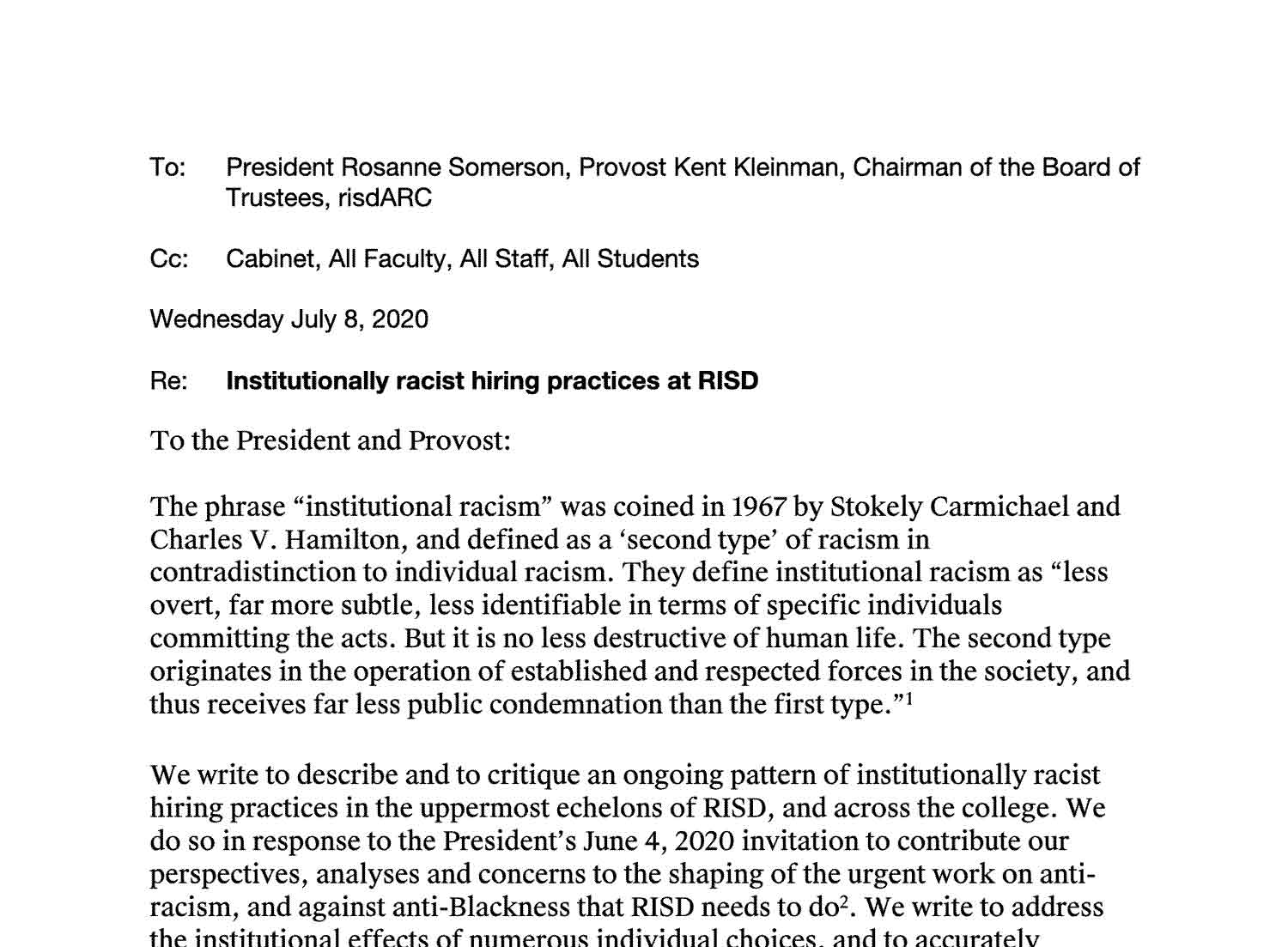

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts. The evidence that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

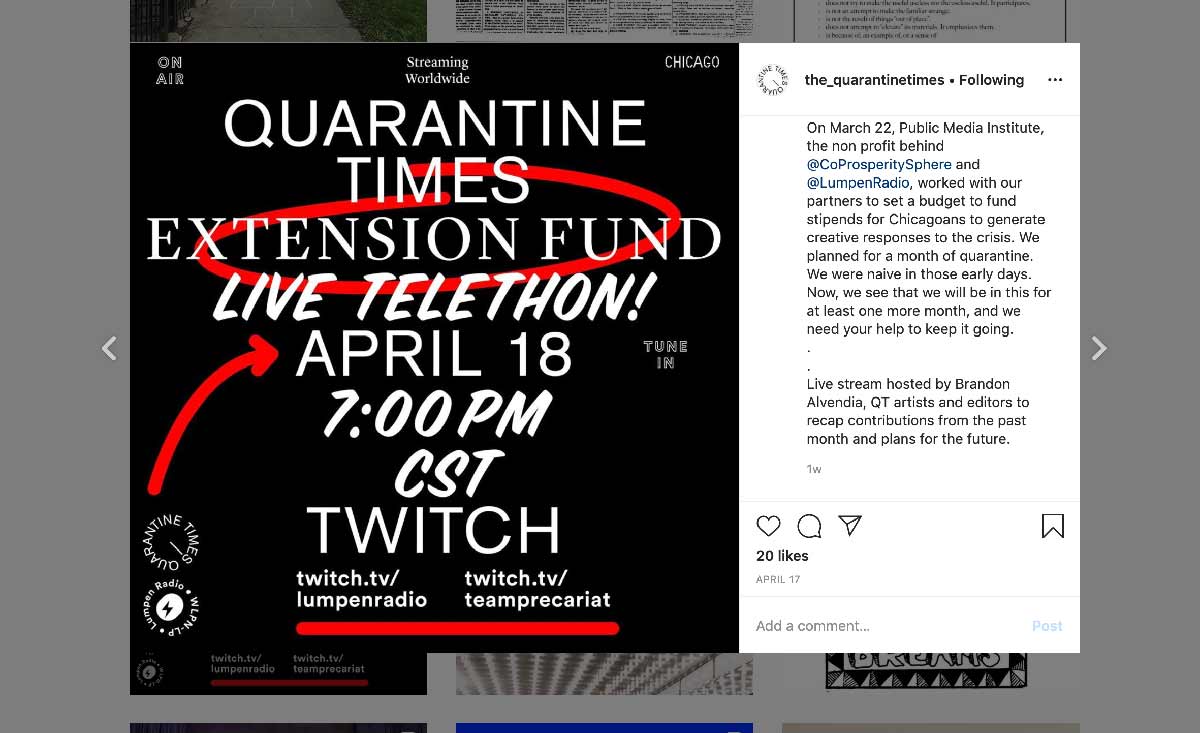

Quarantine Times (April 22, 2020)

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

“Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD,” letter, July 8, 2020 (source)

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or open access zines. All are collective acts of making public.

American Artist, Nora Khan, Caitlin Cherry, Sondra Perry, A Wild Ass Beyond, Apolcalypse RN zine (2018) (source)

Urgent artifacts don’t work without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

Jeffrey Cheung, Unity Press

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

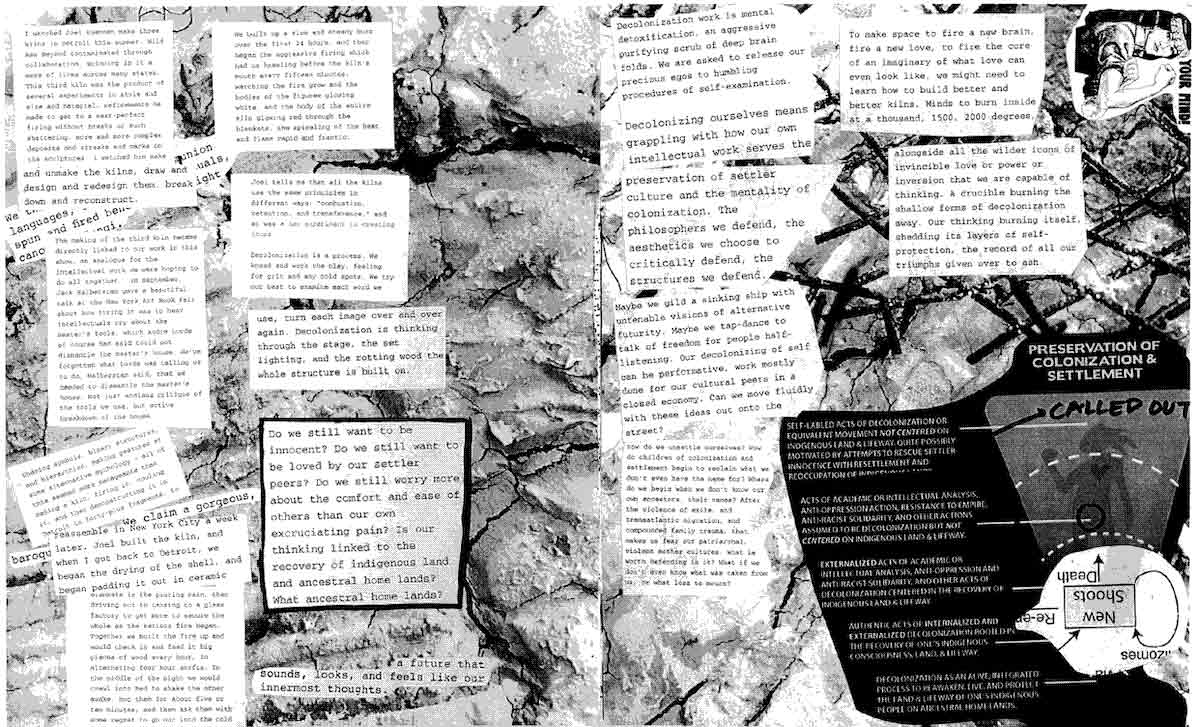

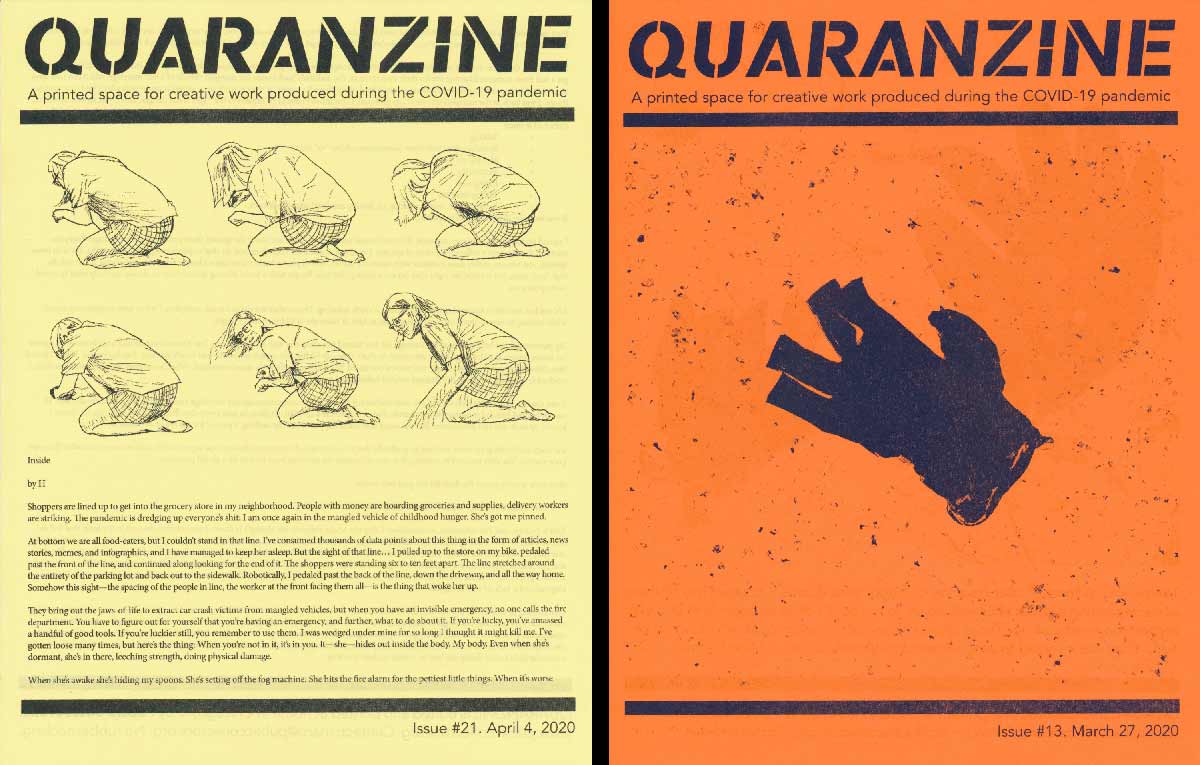

Marc Fischer / Public Collectors, Quaranzine, April 4 and March 27 issues, 2020 (source)

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as a kind of urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today: protests happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing,

Terry Kilby, Robert E. Lee Monument: 6.15.2020, 3D model (2020) (source)

or as an .obj file of a 3D scan of a defaced monument, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and an activist/organizer about mutual aid.

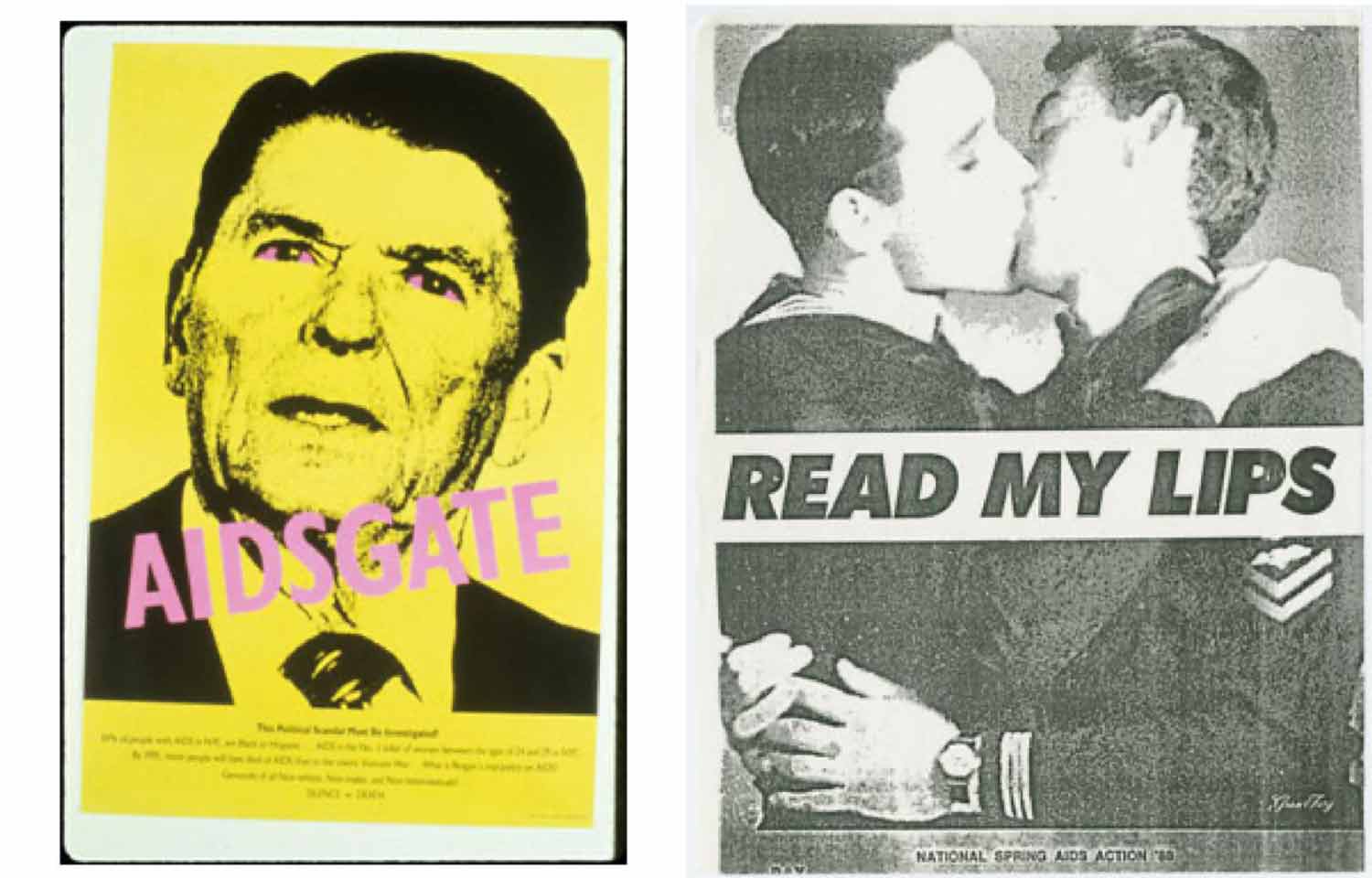

Gran Fury, AIDSgate (1987) and Read My Lips (Boys) (1988) (source)

Urgent artifacts are found throughout history during times of oppression and crisis.

11

RADICAL PUBLISHING AS RESISTANCE AND SURVIVAL

To get closer to urgentcraft, I propose that we use archives like time machines, dialing back into significant moments over the last fifty years to see how others have resisted and persisted through shared, radical acts of publishing. We can learn from those ongoing struggles for liberation and ask them to inform the way we work today.

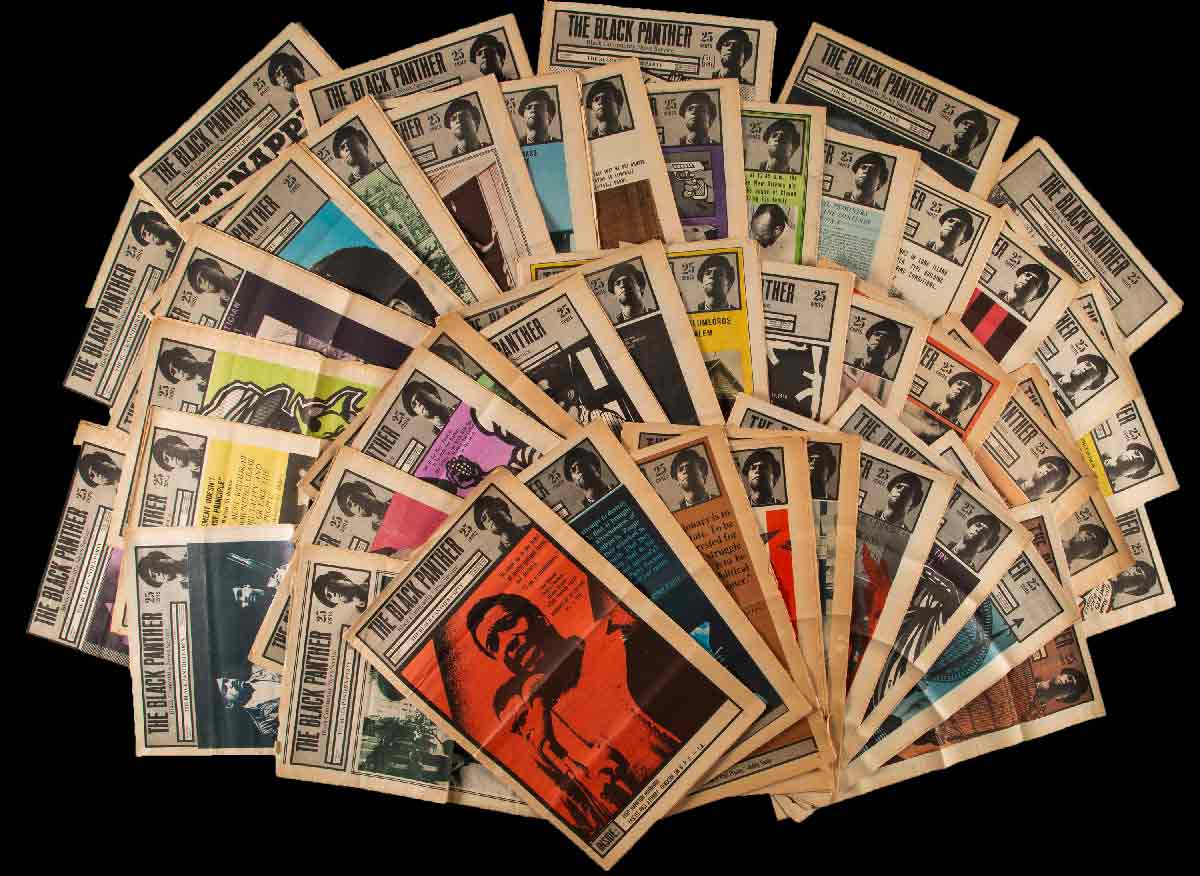

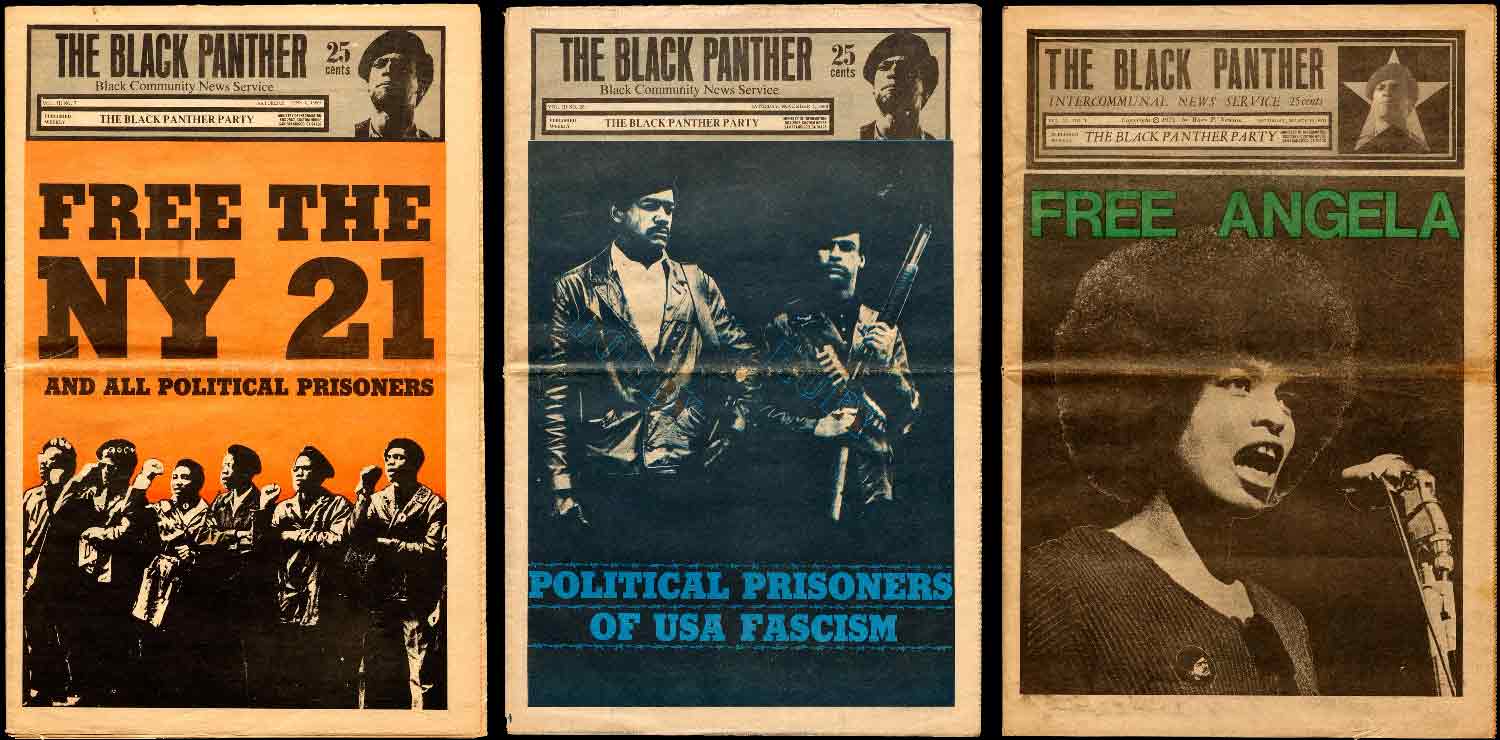

The Black Panther newspaper

Much has been written about the visual impact of The Black Panther Party newspaper, art directed by Emory Douglas, who was the party’s Minister of Culture and the newspaper’s designer and main illustrator.

“This Just In: Emory Douglas & The Black Panther,” Letterform Archive (source)

The political content contained in the more than 500 issues, which was the most widely read Black newspaper in the United States from 1968–1971, is an essential archive of Black struggle and liberation in the US civil rights movement. How the weekly newspaper was distributed is less discussed in design circles.

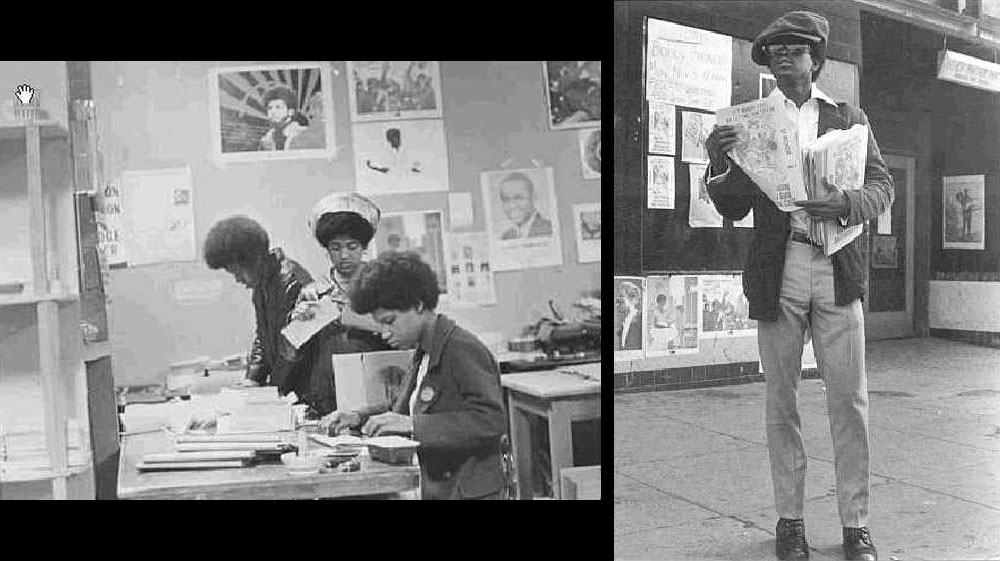

“Wednesday Nights at Central Distribution” (source)

Panthers Fred Bennett and Judi Douglas selling The Black Panther newspaper (source)

Participation in The Black Panther Party newspaper ecosystem was supported by the act of delivering it. Panthers themselves were responsible for dispersing the news, and would sell the paper in laundromats, street corners, and other public spaces. Each distribution point was also an opportunity to learn, interact, and engage between people. The quality and urgency of the information distributed, and the open access to party members themselves, can be seen as a kind of wealth—not a wealth of accumulation, but a shared wealth of needs emerging from within a struggling community.

Panthers selling The Black Panther newspaper in public (source)

As a shared practice, The Black Panther Party newspaper was not just a published product, but an alternative publishing economy that prioritized care and community need. This was negotiated and fulfilled collectively through acts of mutual aid. The cost of the paper was 25 cents, and sellers would keep a dime from each sale. The exchange of money enabled the newspaper to continue printing, but also directly benefited those who labored in its production and distribution, as well as those who received the actual news.

Getting The Black Panther newspaper ready for national distribution, Black Panther National headquarters, Berkeley, CA (source)

The form, a printed newspaper, was conventional—but all other aspects of the project challenged normative expectations, from its politics to its design to its method of distribution to its economic model to its public impact. It was urgent publishing in the timeliness of its delivery, and the necessity to engage and commune in the exact moment of exchange. This was radical publishing because it interfered with mainstream ideas about Black life and survival in the US, illustrating and amplifying the conversation around racial injustice. It gave voice to Black communities in crisis. It was radical publishing because the distribution of the newspaper created and benefited a mutual aid network of engaged participants who visibly performed labor, selling (and purchasing) the paper in open, public space, by-passing the usual channels of delivery and consumption, while working against the conventions of white-controlled, white supremacist media.

12

WE REALLY NEED TO DO SOMETHING ABOUT PUBLISHING

The Combahee River Collective’s first black feminist retreat, July 1977, in South Hadley, Massachusetts. Barbara Smith, second from left. (source)

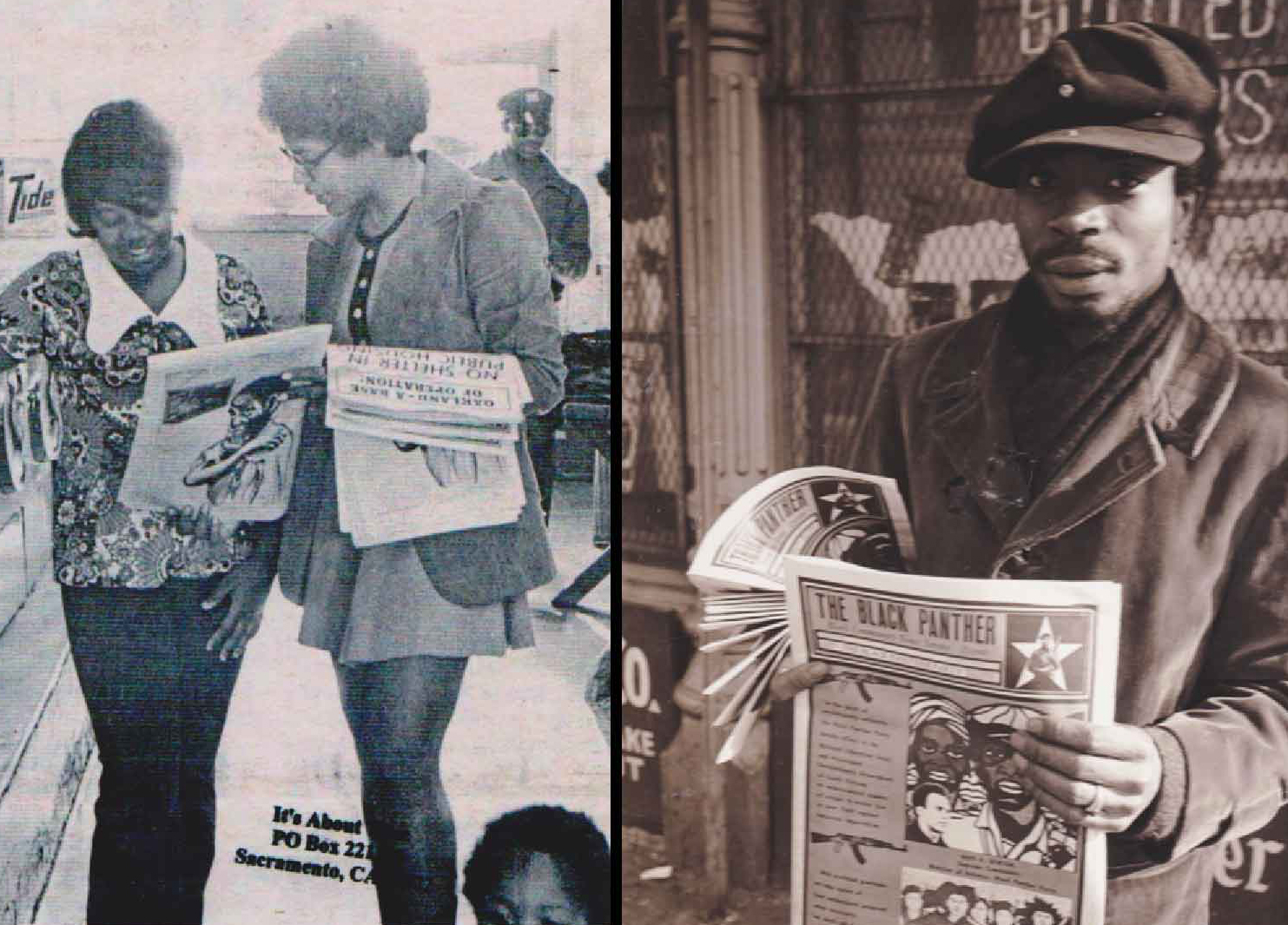

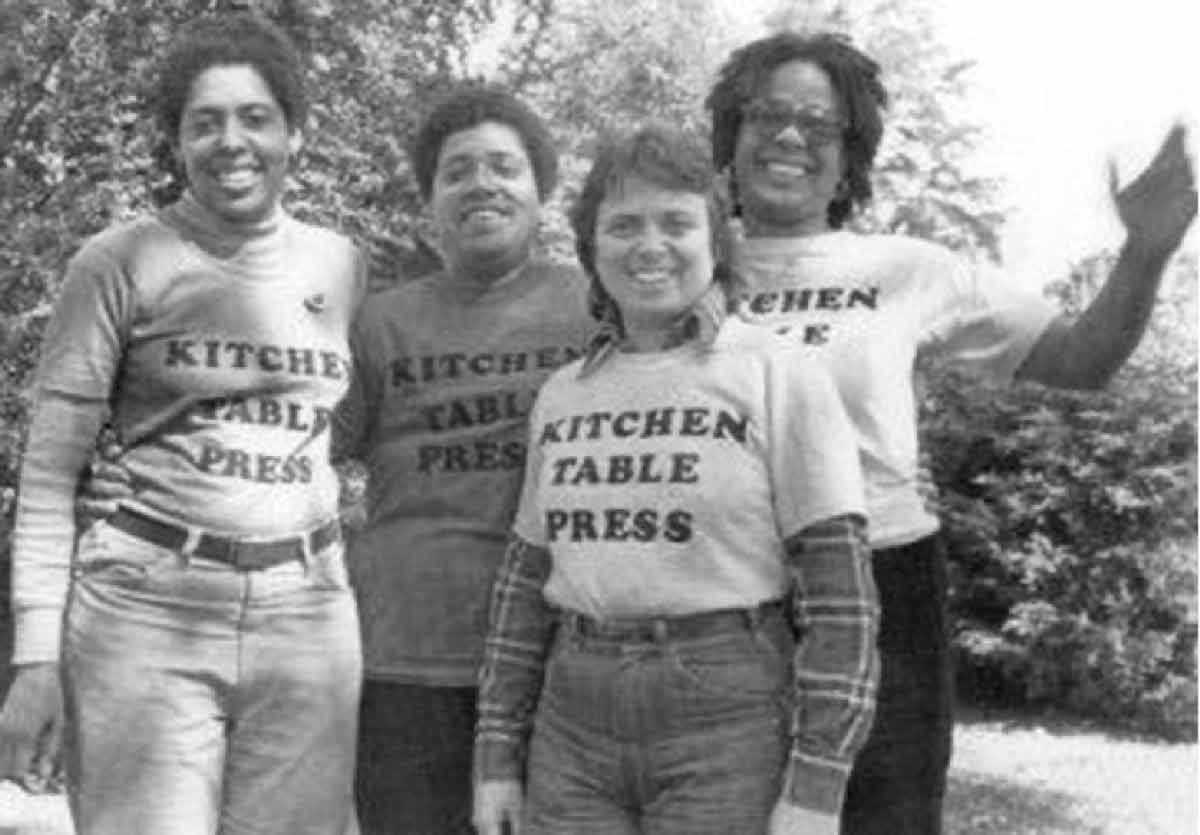

Just a few years later, a group of women formed the Combahee River Collective by splitting off from the Boston chapter of the National Black Feminist Organization. The Combahee River Collective was a class-conscious, sexuality-affirming organization, and one of its co-founders was Barbara Smith, a powerful organizer, activist, and publisher who later formed Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, in collaboration with Audre Lorde and other writers and poets.

Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press

Barbara Smith helped create these spaces for radical publishing by turning away from the oppression-based, exclusionary practices of commercial and academic publishing, as well as from so-called alternative publishing. In “A Press of Our Own—Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press” (1989) Smith gives an account of the founding of Kitchen Table, beginning with a telephone conversation with Audre Lorde in 1980, in which Lorde said: “We really need to do something about publishing.”

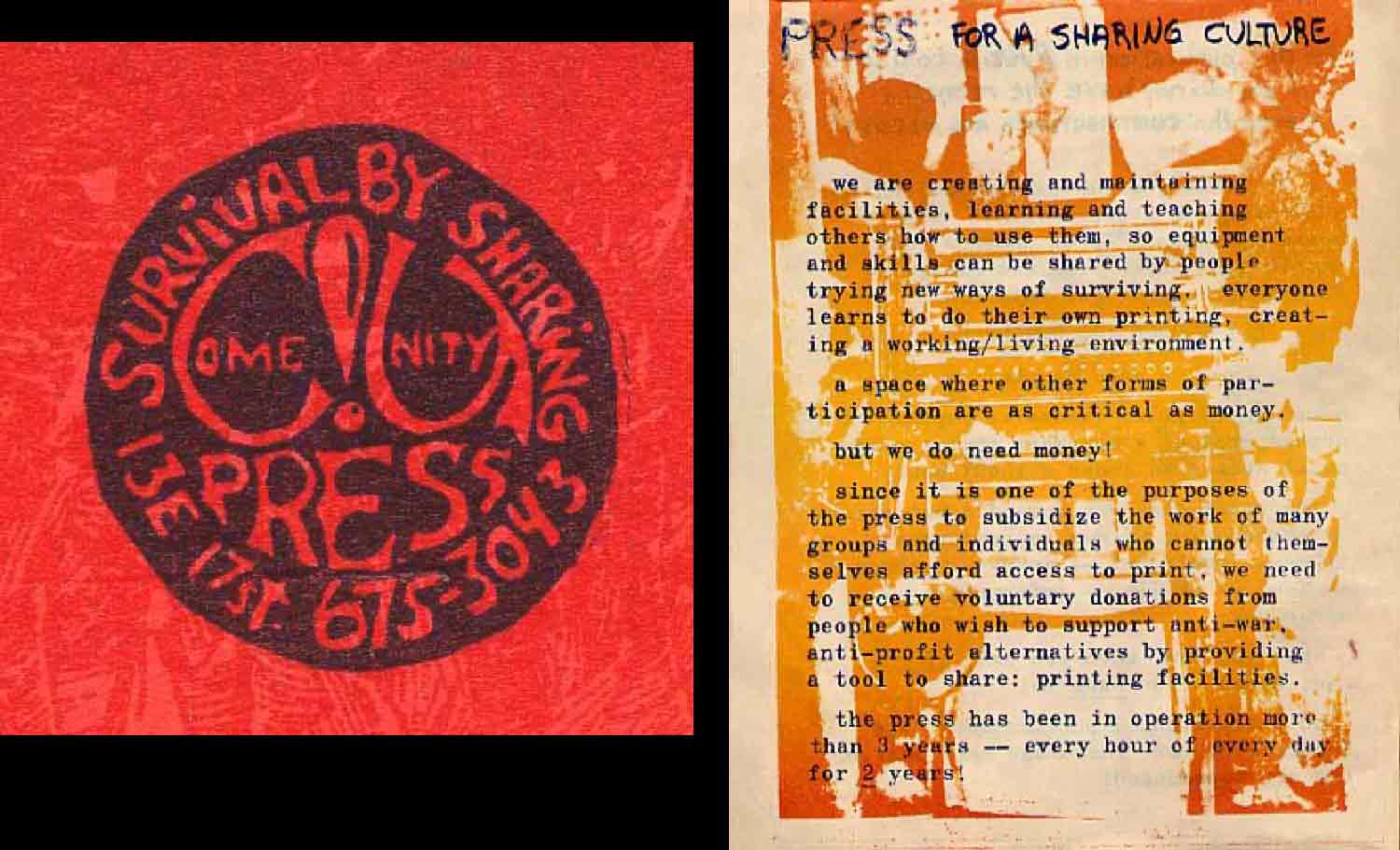

Come!Unity Press, 1970s (source)

Radical publishing has been used throughout history as a form of survival. Gestures of making public that move away from and refuse whiteness, heteronormativity, capitalism, and settler colonialism give power to deeper acts of organizing by distributing new and disruptive thinking.

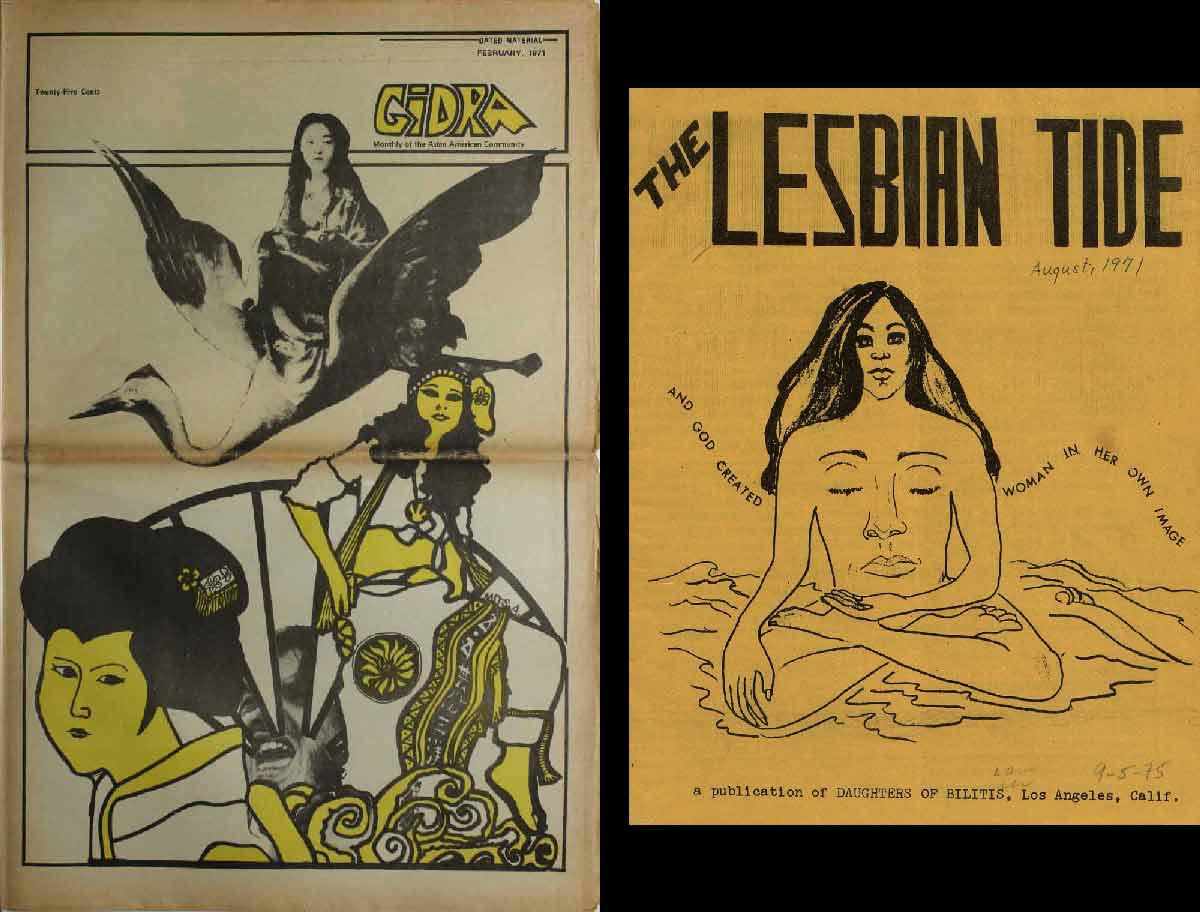

left: Gidra, Volume III, No. 2, February 1971 (source) / right: The Lesbian Tide, Volume 1, Issue 1, August 1971 (source)

Radical publishing fuels change through the circulation of urgent artifacts and the publics that form around them.

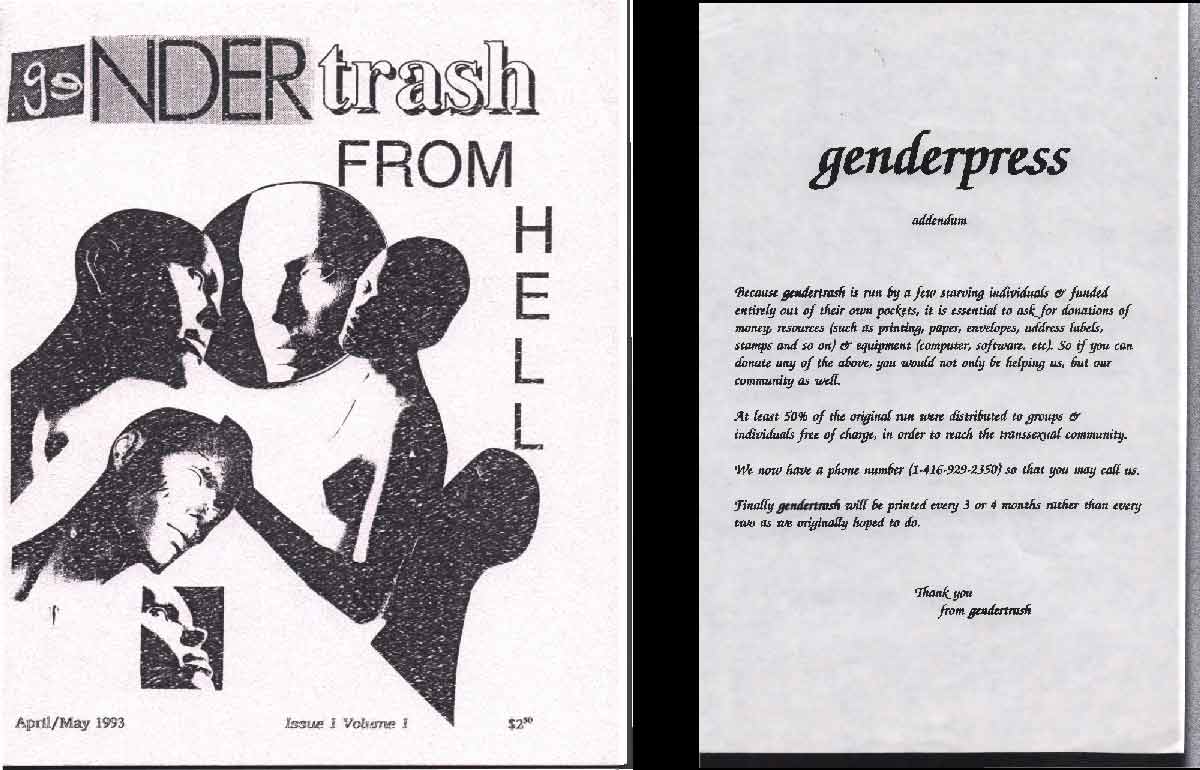

Gendertrash From Hell 1, Issue 1, Volume 1, April/May 1993 (source)

Projects like The Black Panther newspaper, Kitchen Table, Come!Unity Press (NYC, 1970s), and other community-based publishing projects prioritized generosity and collaboration out of a necessity to work collectively. Focusing on communal care, and giving it form through the creation of urgent artifacts, is itself a radical act under capitalism.

13

INTERFERENCE, INTERRUPTION, AGITATION, VISIBILITY

Another strategy is to interrupt the narrative through visibility, interference, and agitation.

IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A., jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs. (source)

This is why David Wojnarowicz’s jacket is such a powerful, radical artifact. He wore it to an ACT UP demonstration at the height of the AIDS pandemic. It’s an act of design, it’s art, and it’s a gesture of making public—but its real power is as an urgent artifact, one that contains the potential for radical action. It’s less the work of a specific artist who publishes, and more the plea for communal responsibility and care by a political subject, struggling in illness against state negligence (Wojnarowicz died of AIDS four years later). It’s an urgent call to action.

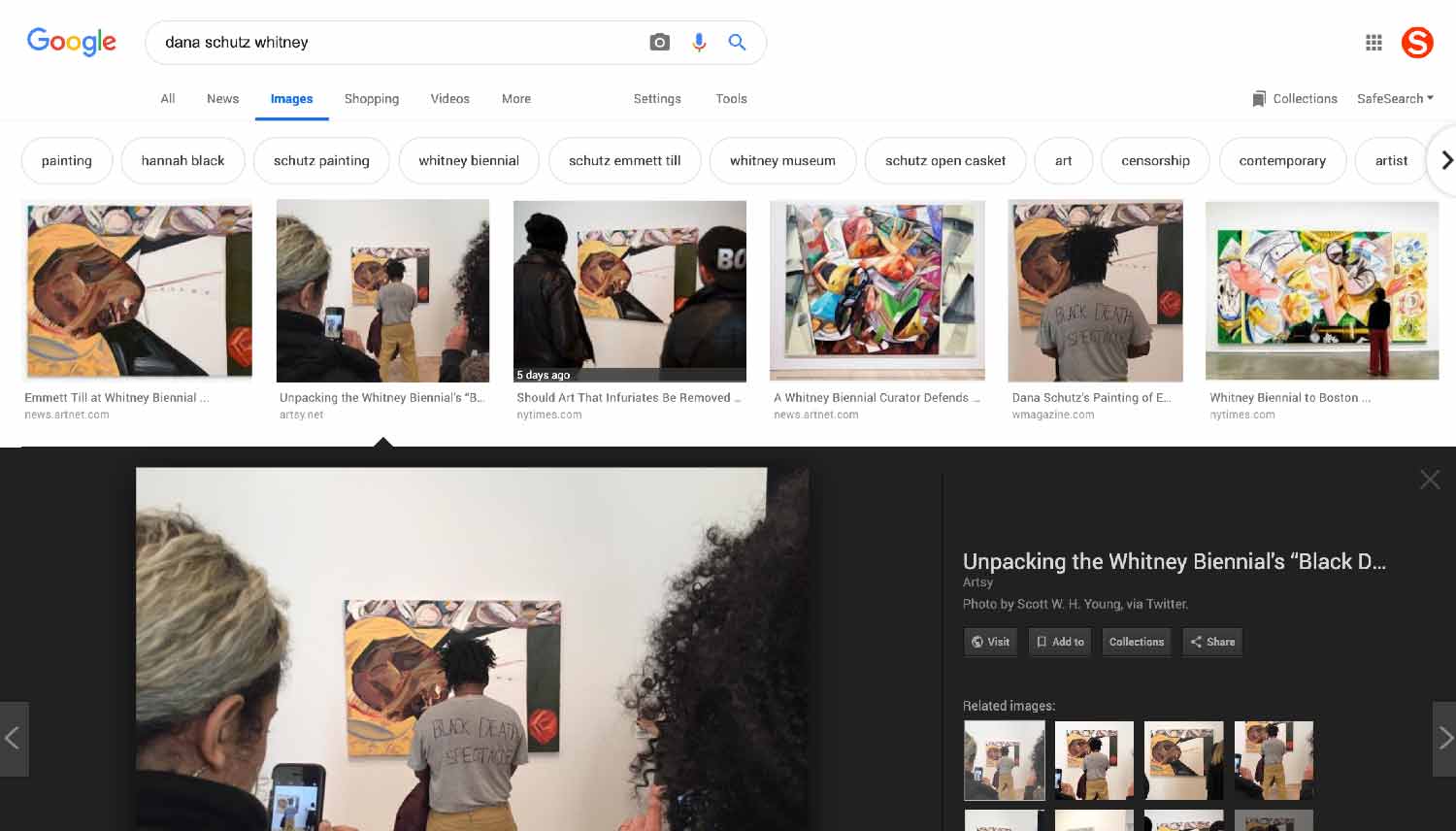

Parker Bright, protest at Whitney Biennial (March 17, 2017)

Echoing Wojnarowicz, artist and activist Parker Bright used their body to intentionally obscure the view of a controversial painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz at the 2017 Whitney Biennial. With their body in the way and the message “Black Death Spectacle” hand-written on their back, they interfered with the ultimate smooth flow of an undisturbed art-viewing experience. And by doing so they disturbed the visual culture of violence that white supremacy enacts through the art world and the artists it protects.

Google search, “dana schutz whitney”

Blocking the view, Parker reduced the legibility of the painting in one dimension, but enhanced it in another, by giving it a new caption. And as their act was photographed and amplified, they occupied digital spaces, too—agitating the narrative and forever bonding their message with the painting in digital archives. To borrow a term from US statesman and civil rights leader John Lewis, Parker caused good trouble by using their own visibility to get in the way.

14

REFUSAL, ILLEGIBILITY

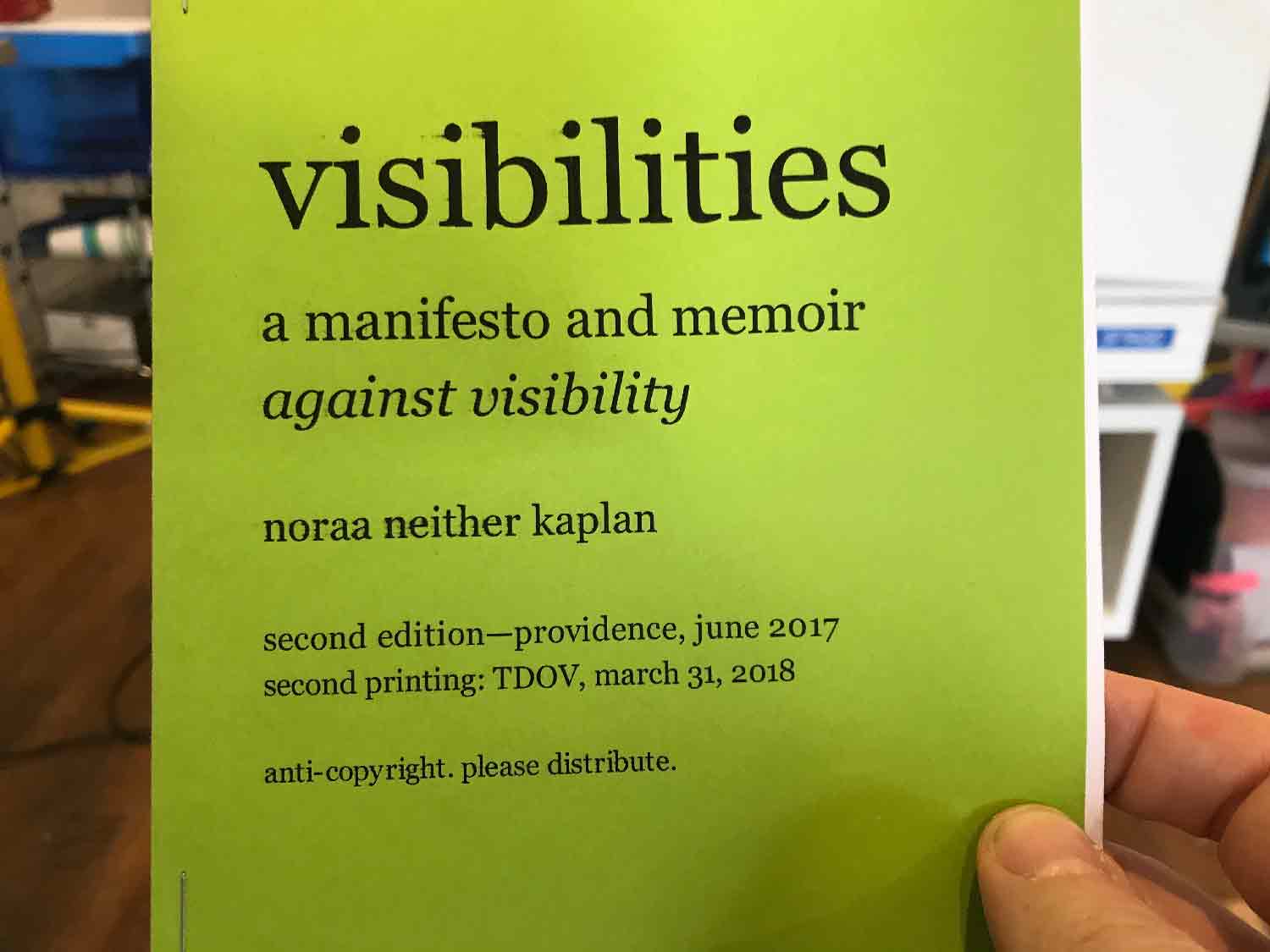

noraa neither kaplan, visibilities zine (2018)

Wherever there is visibility, there is privilege—the ability to use one’s body and to have it read clearly. For many bodies this isn’t safe. And so refusal and illegibility are also tactics for us to look at here. The act of refusal—deliberately turning away from structures that exclude and erase—remains an important form of critique, resistance, and survival under oppression.

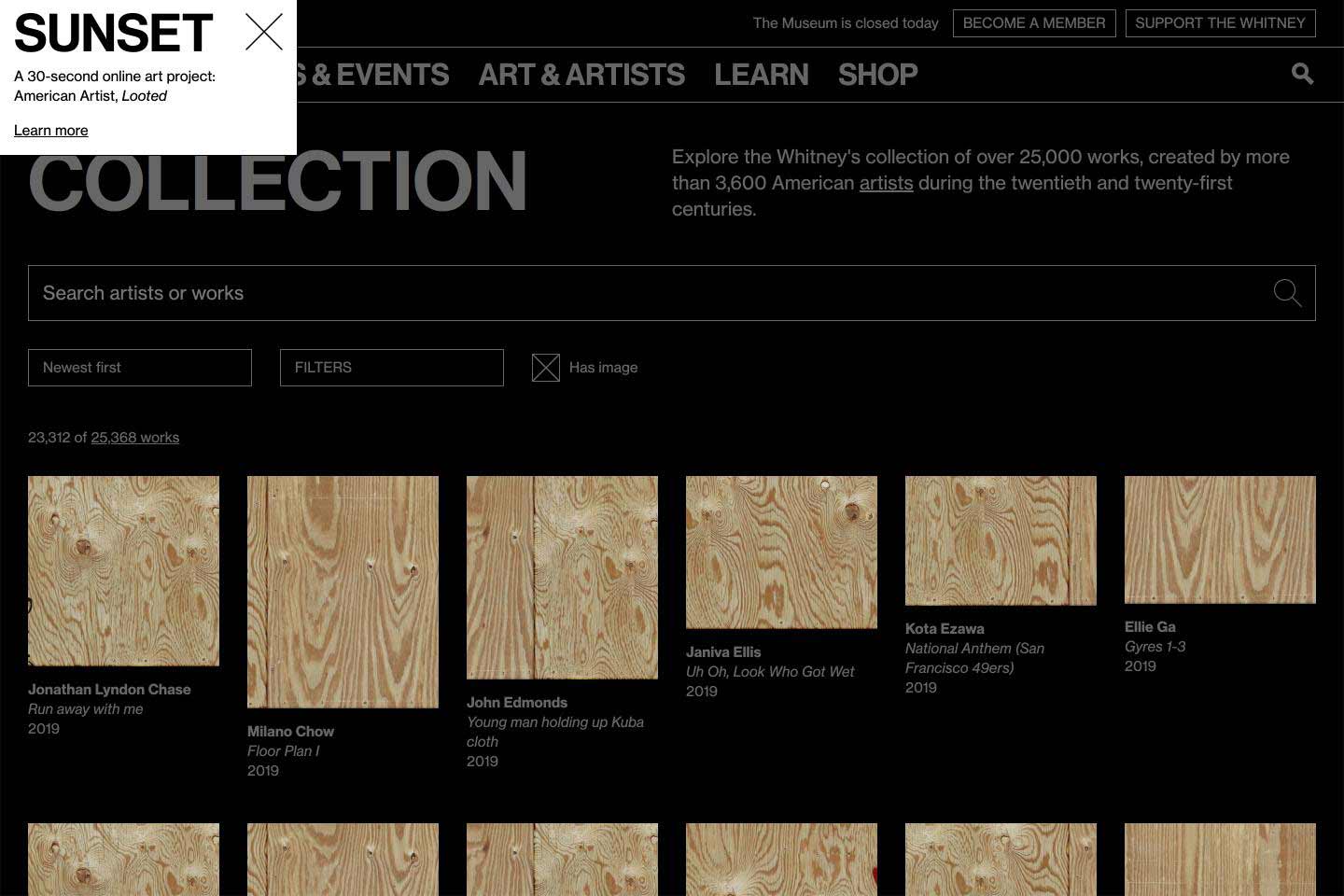

American Artist, Looted (2020)

Many artists who work against, manipulate, or interfere with visibility today are fighting for racial, transgender, mental health, immigration, and other forms of justice.

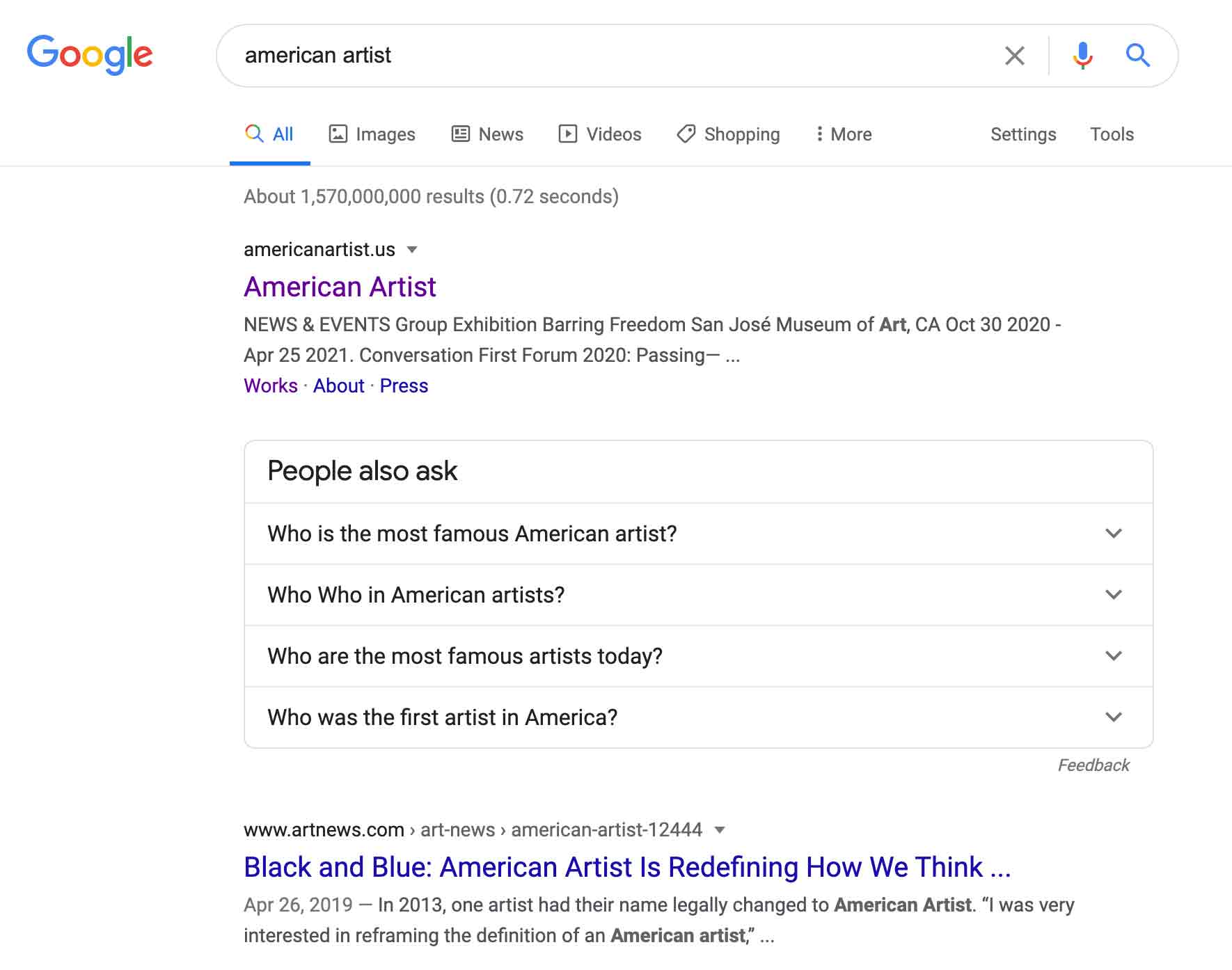

Google search, “American Artist”

American Artist legally changed their name in 2013 as an act of refusal and illegibility, reframing both of the words: American and Artist. In refusing to use their birth name, they manipulate legibility and how one is properly “read” (whether socially, algorithmically, or by the state), denying and shaping perception around who gets to claim the privilege carried in these words, and foregrounding how whiteness persists in art world spaces.

American Artist, A Refusal (2015–16)

American Artist continues to evolve an important body of work, as well as writings, using techniques of refusal and redaction to agitate the ultimate smooth flow of art world purity.

15

STAYING WITH THE MESS

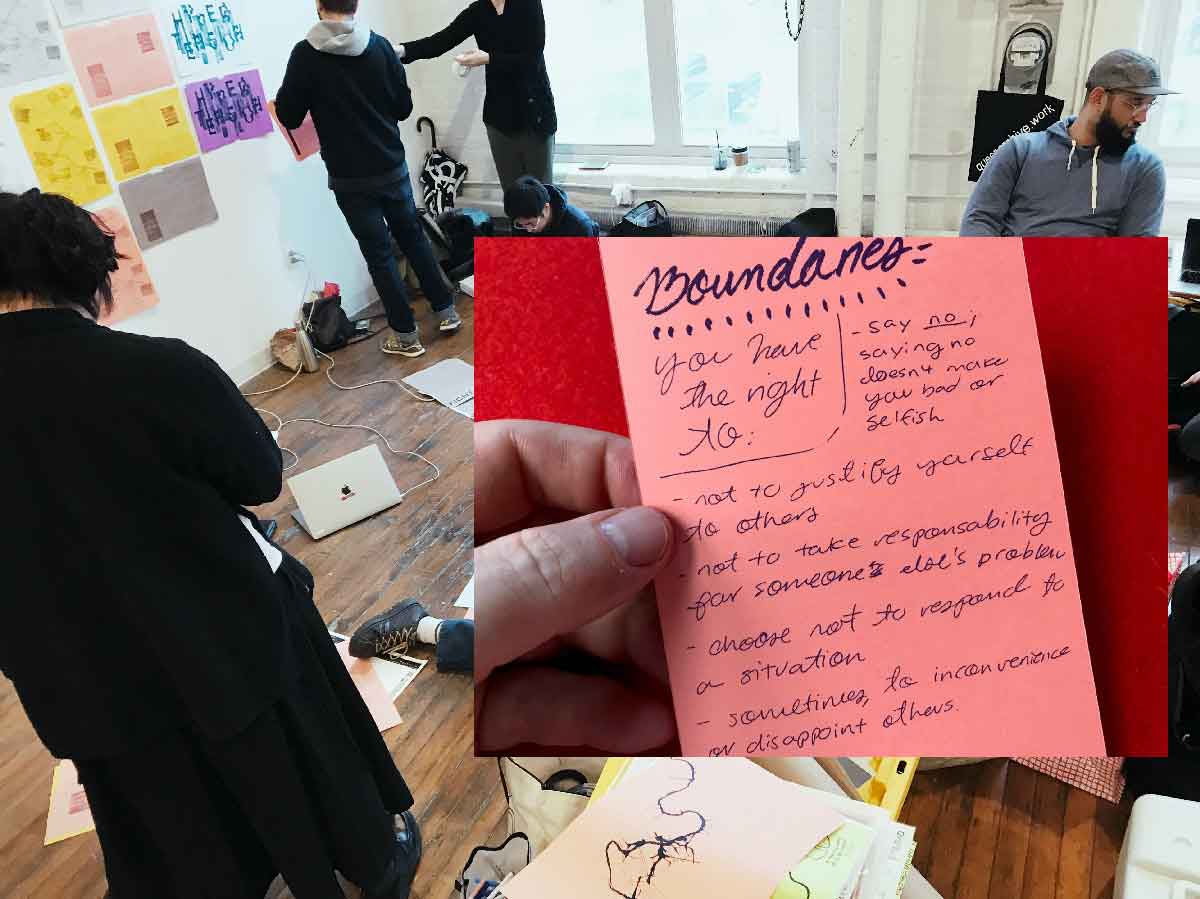

Urgency Lab workshop at Brown University (2019)

Right now, I’m trying to bring queer strategies of resistance and survival into the spaces around me, whether they be in my own practice, in teaching, or in community building.

Urgency Lab at RISD (2019)

In 2019, I created Urgency Lab, a series of classes and workshops. In the past, I worked to control each of the learning outcomes when teaching. But questioning more typical approaches to pedagogy means dealing with uncertainty in the classroom.

Urgency Lab at RISD (2019)

With students at the Rhode Island School of Design, we tried to stay with the discomfort of not always knowing those outcomes. We explored what it feels like to step away from the institution and work outside of traditional values in higher education, like exceptionalism, competition, and perfection; we even left the physical campus. What would it mean for a classroom to be a space for communal care? Eventually we realized that the urgency was right there in the room with us, in the form of our own vulnerabilities.

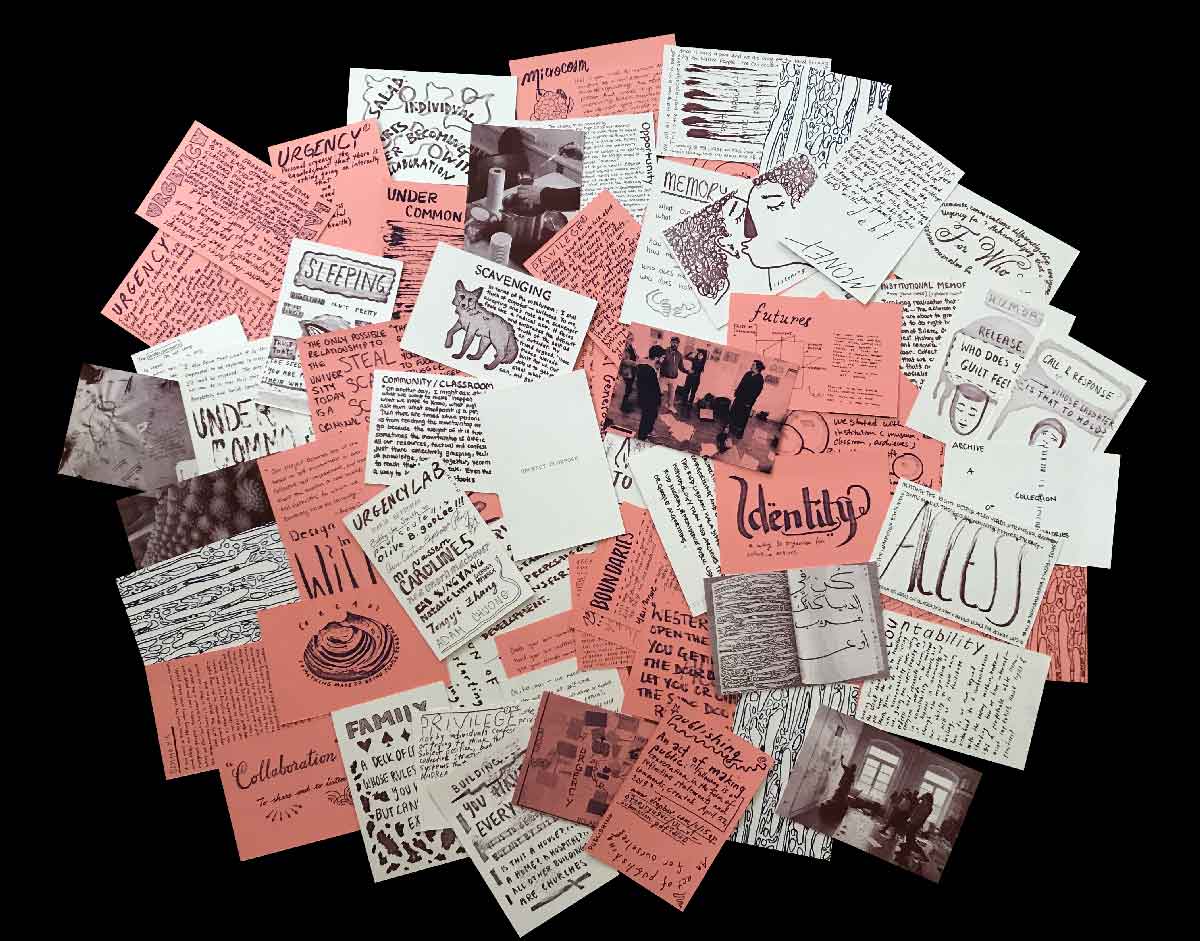

Urgency Cookbook (2019)

At the conclusion of the class we hesitated to produce any kind of validating object or product. But we did publish a risograph-printed deck of cards that foregrounds the values that emerged during the semester. Urgency Cookbook was written and hand-drawn by everyone in the class from a collaborative doc that we worked on for several weeks, full of ingredients and recipes for survival and communal care.

Teaching has become a way for me to focus less on personal accomplishment and power and more on an engaged pedagogy, after bell hooks, that tries to empower everyone in the room, with a commitment to dialogue, shared vulnerability, and criticality.

16

QUEER ARCHIVE WORK

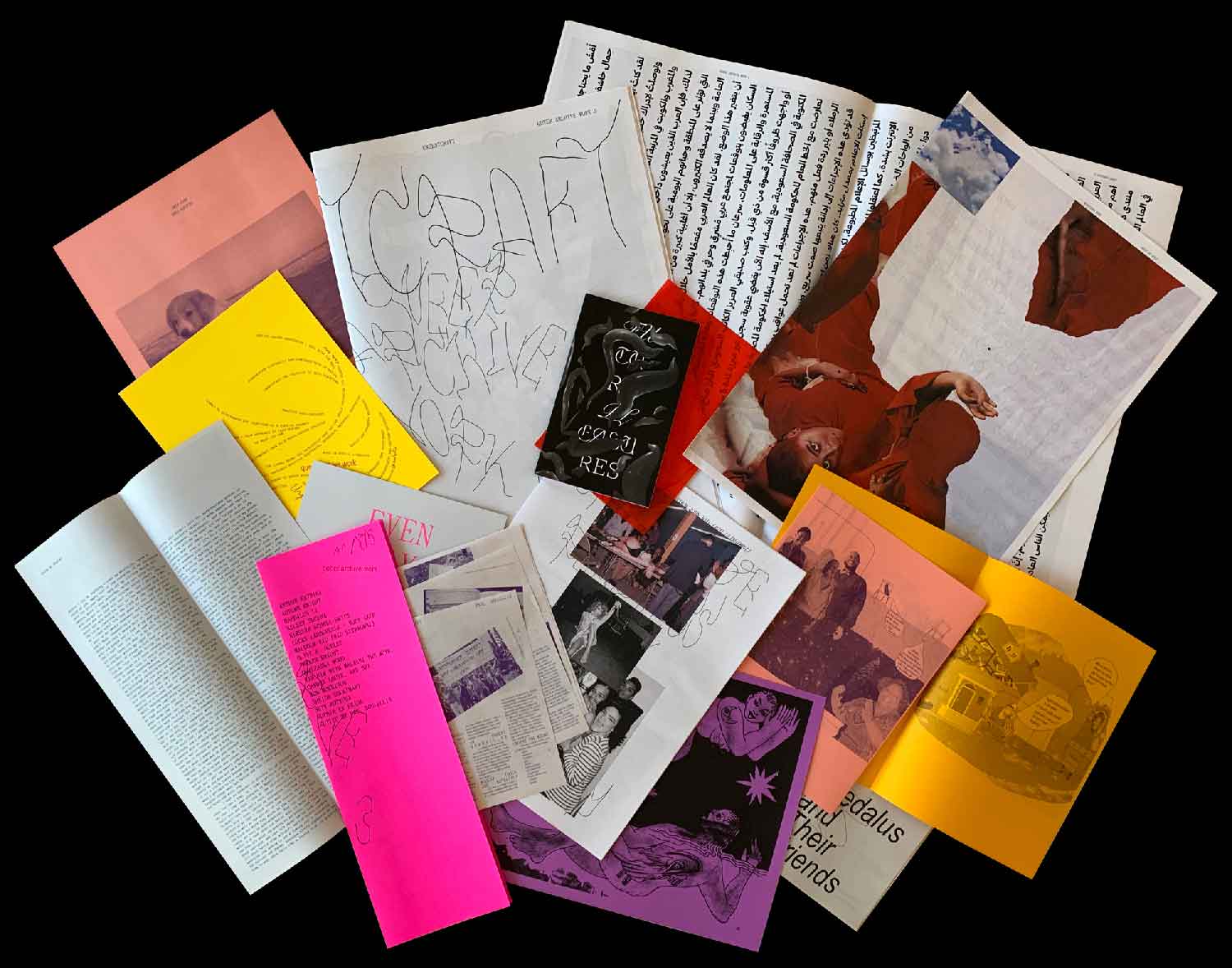

Queer.Archive.Work #3 (2019)

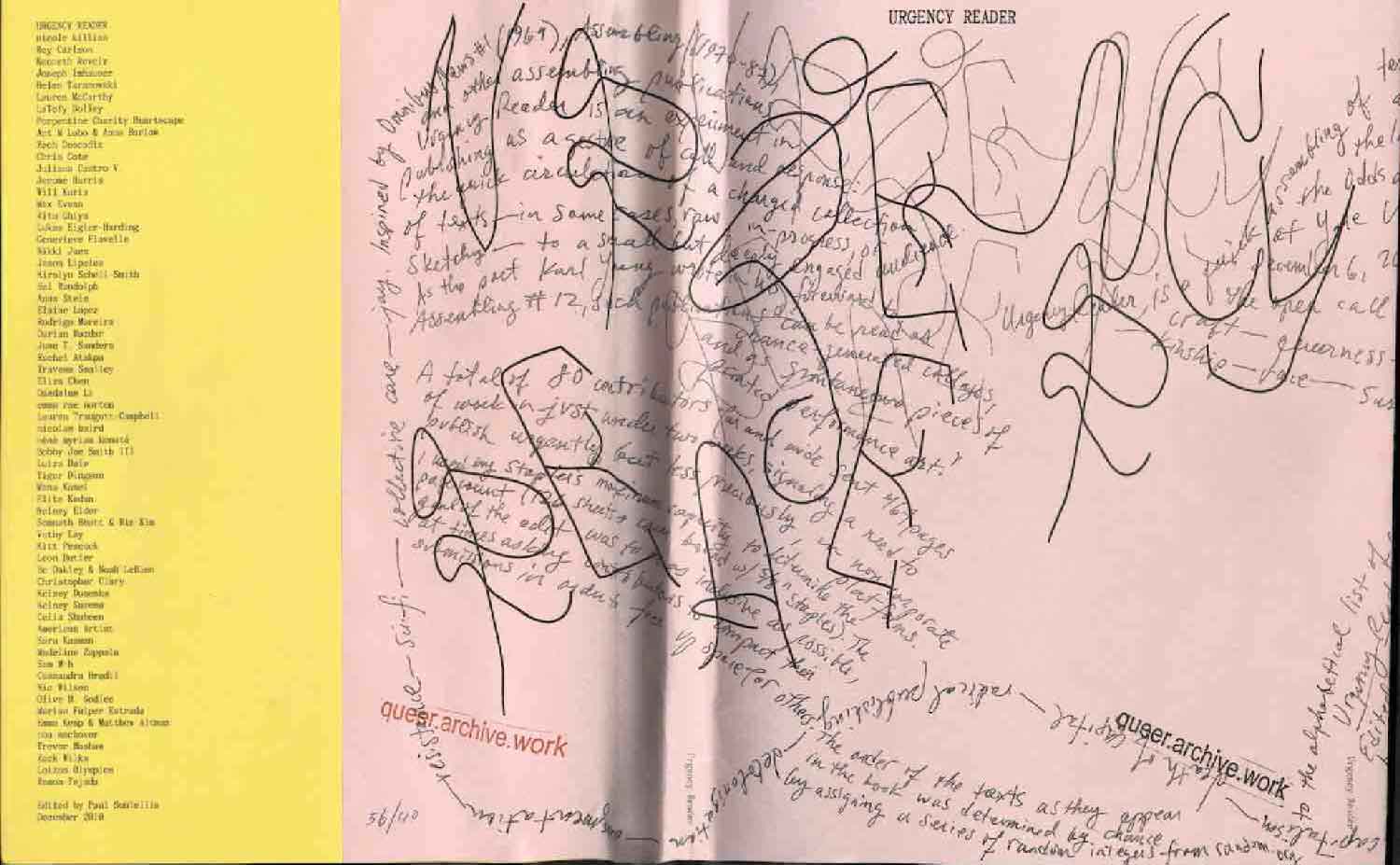

Outside of teaching, I’m developing a practice that prioritizes collaboration and making space for other voices. Queer.Archive.Work began with this question: how might a publication provide a queer space for collective care? The first three issues featured the words and images of 50 artists and writers making good trouble with their work, with a focus on LGBTQIA+ and others folks traditionally left out of or erased from archives.

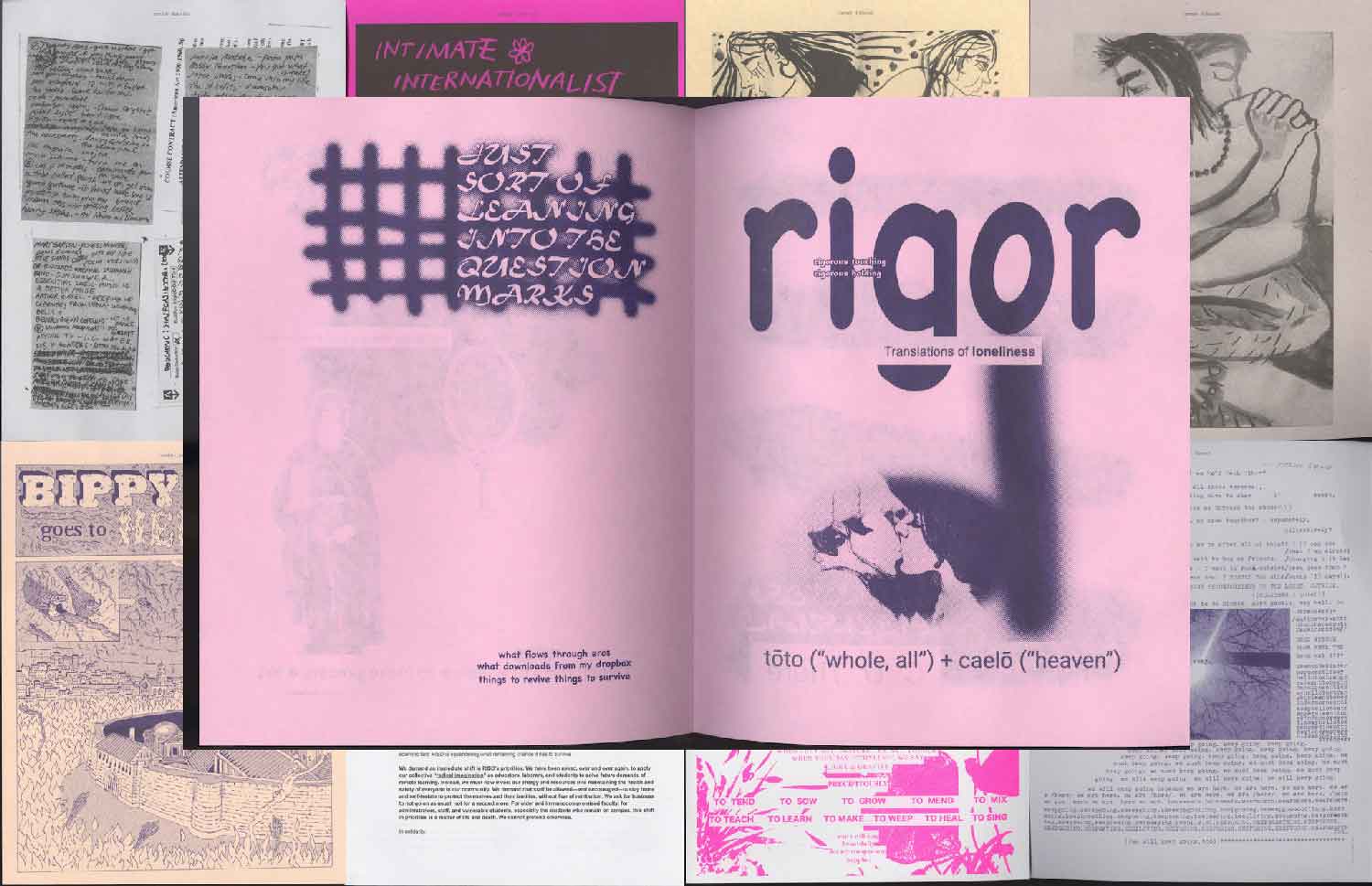

These publications were designed to make a physical mess as the components slide out of their containers. This is when I began thinking intentionally about urgentcraft in the context of my own design practice—staying with the mess to allow for an abundance of meaning, and no dominant narrative. In Queer.Archive.Work, most of the printed items remained un-bound, using no glue, staples, or tape. Instead, the parts were folded, nested, and enveloped to encourage new kinds of readings.

Queer.Archive.Work installation at Printed Matter’s NY Art Book Fair (2019)

Our installation at Printed Matter’s NY Art Book Fair in 2019 tried to display this deliberate non-linearity and lack of hierarchy. This was not just about the optics of making a mess, or the visual confusion of illegibility. The space was designed to discourage a quick, fixed read, and empower visitors to do the work of shaping the material themselves.

Urgency Reader 1 (2019)

Through Queer.Archive.Work, I also published two issues of Urgency Reader.

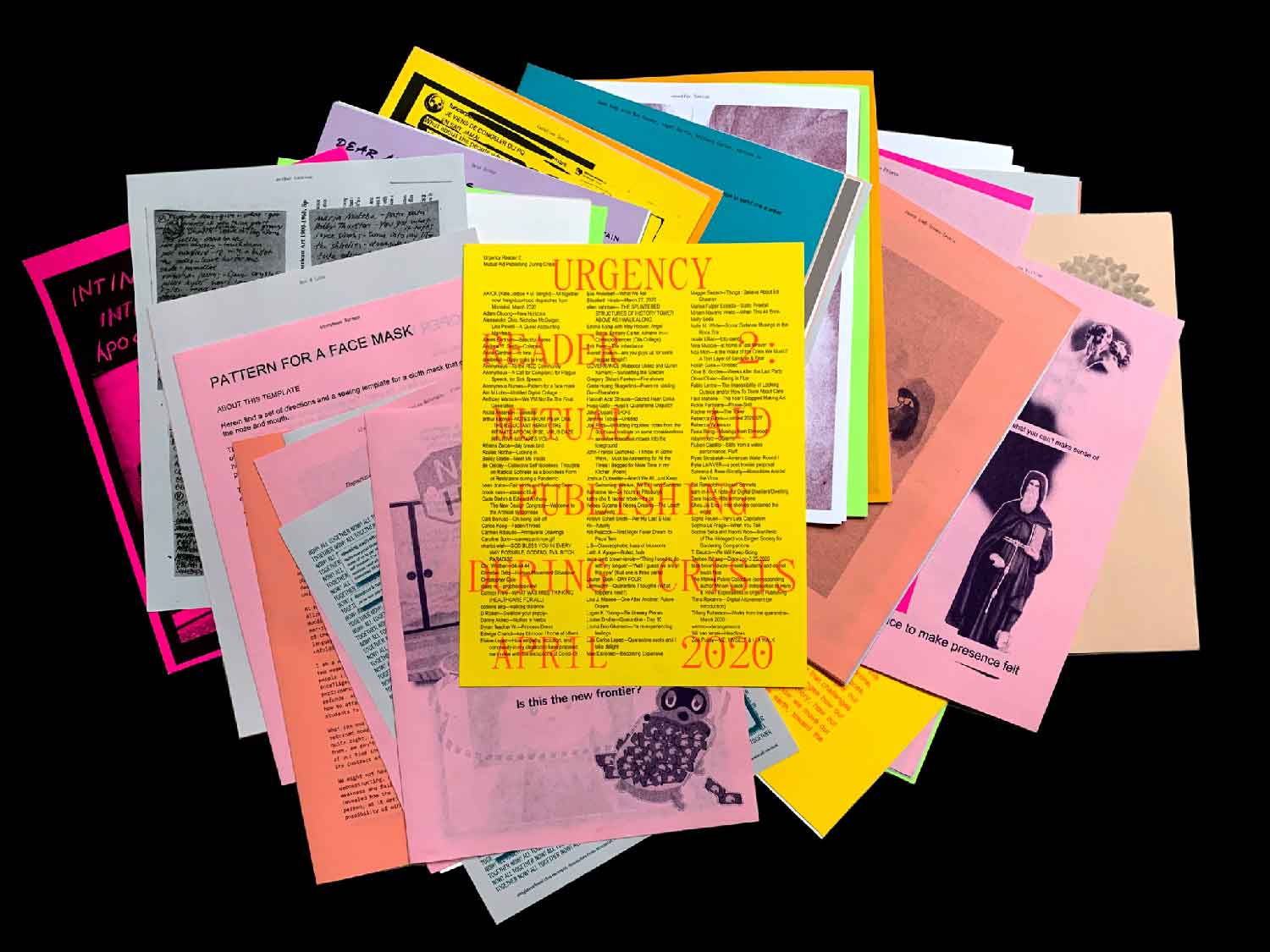

Urgency Reader 2 (2020)

The second issue was made at the start of the COVID pandemic, just as the US was shutting down in March 2020. I posted an open call, and 110 contributors submitted work reflecting observations and impressions during quarantine. Everything was risograph printed.

nicole killian, Urgency Reader 2 (2020)

It was also a mutual aid project, using grant funding to distribute money to all of the contributors, who either accepted the compensation or donated it back to the pool.

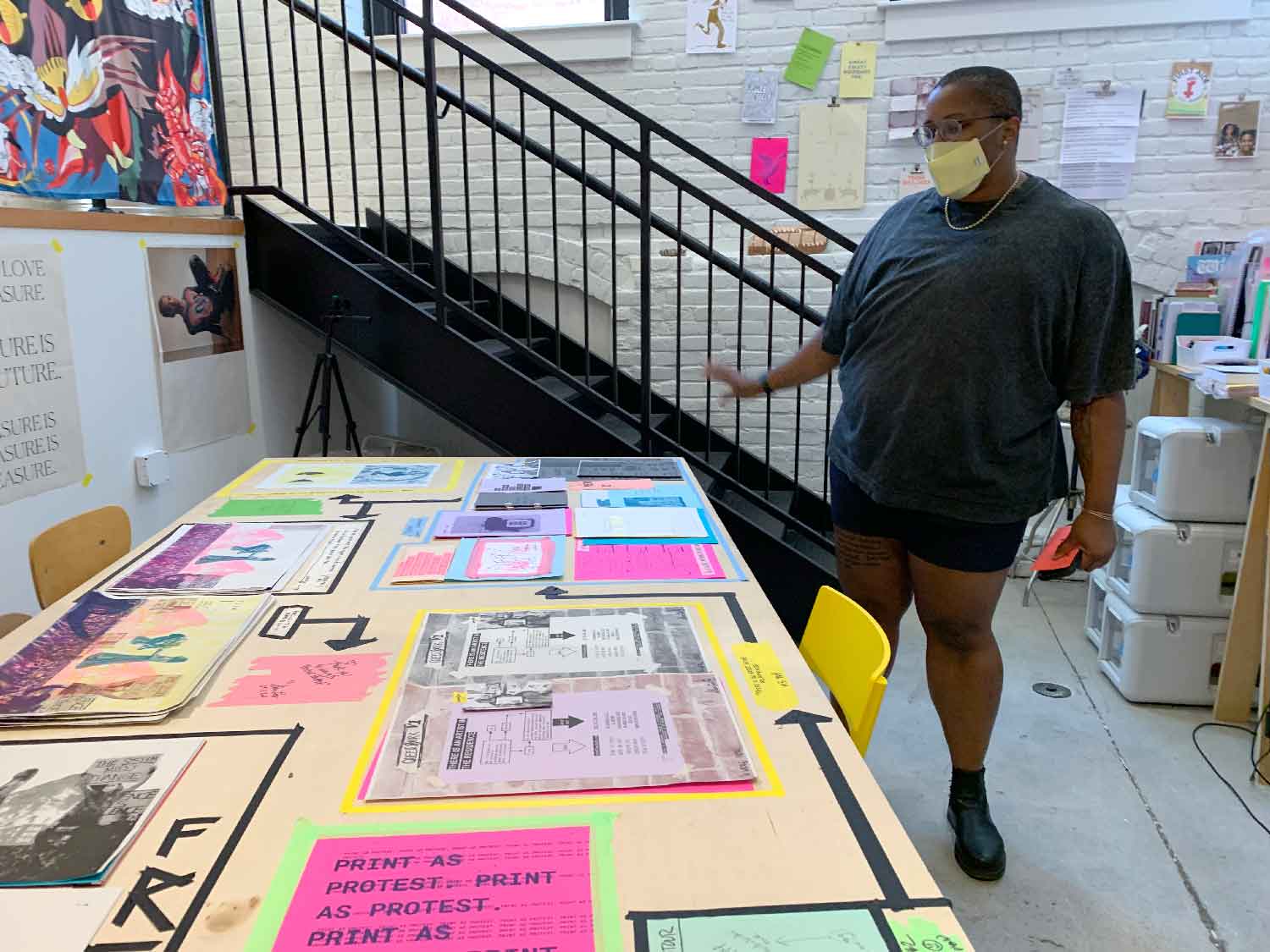

Sloan Leo, Queer.Archive.Work Artist-in-Residence (September 2020)

Recently, I decided to transform Queer.Archive.Work from a publishing practice into a non-profit community space, and besides teaching, this is where all of my energy goes now. I’m interested in how a physical space can be porous, how open access to tools can be a form of community empowerment—in this case a shared risograph printer in a publishing studio. This is about bringing engaged pedagogy out of the school and into a more open and diverse community, away from larger institutions.

Nora Khan working at Queer.Archive.Work (March 2020)

Queer.Archive.Work is now a community publishing space, both physically and online. QAW is always free and open to anyone, prioritizing queer and trans, Black, Indigenous, artists and writers of color, and others who haven’t necessarily had easy access to traditional art world spaces.

Queer.Archive.Work Library

Artists-in-residence and visitors to QAW can use a growing library of zines, books, and unusual examples of experimental publishing for inspiration and research.

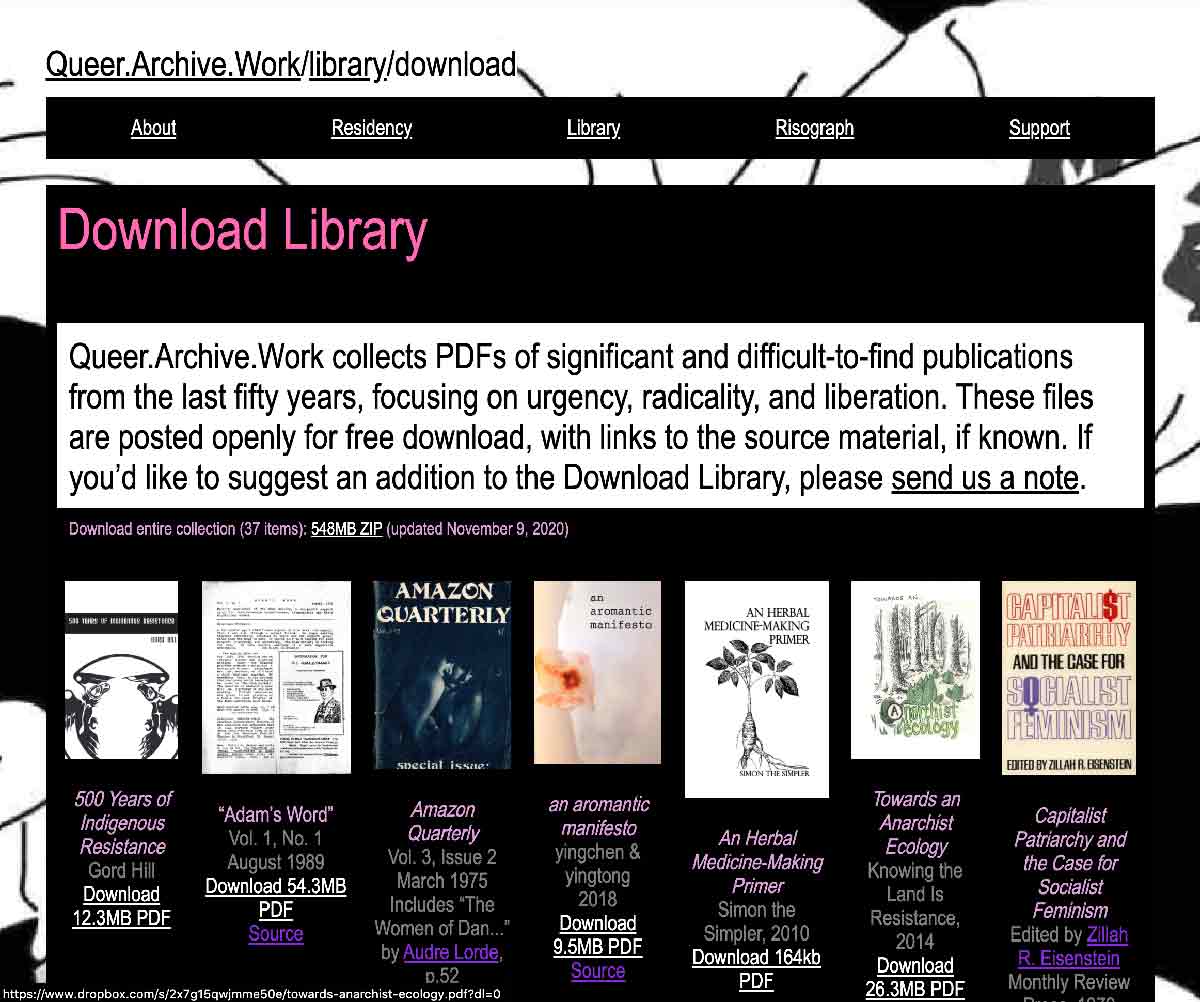

Queer.Archive.Work Download Library

The Download Library is our own time machine of independent publishing through history, focused mostly on urgency, radical thinking, and liberation in the last fifty years.

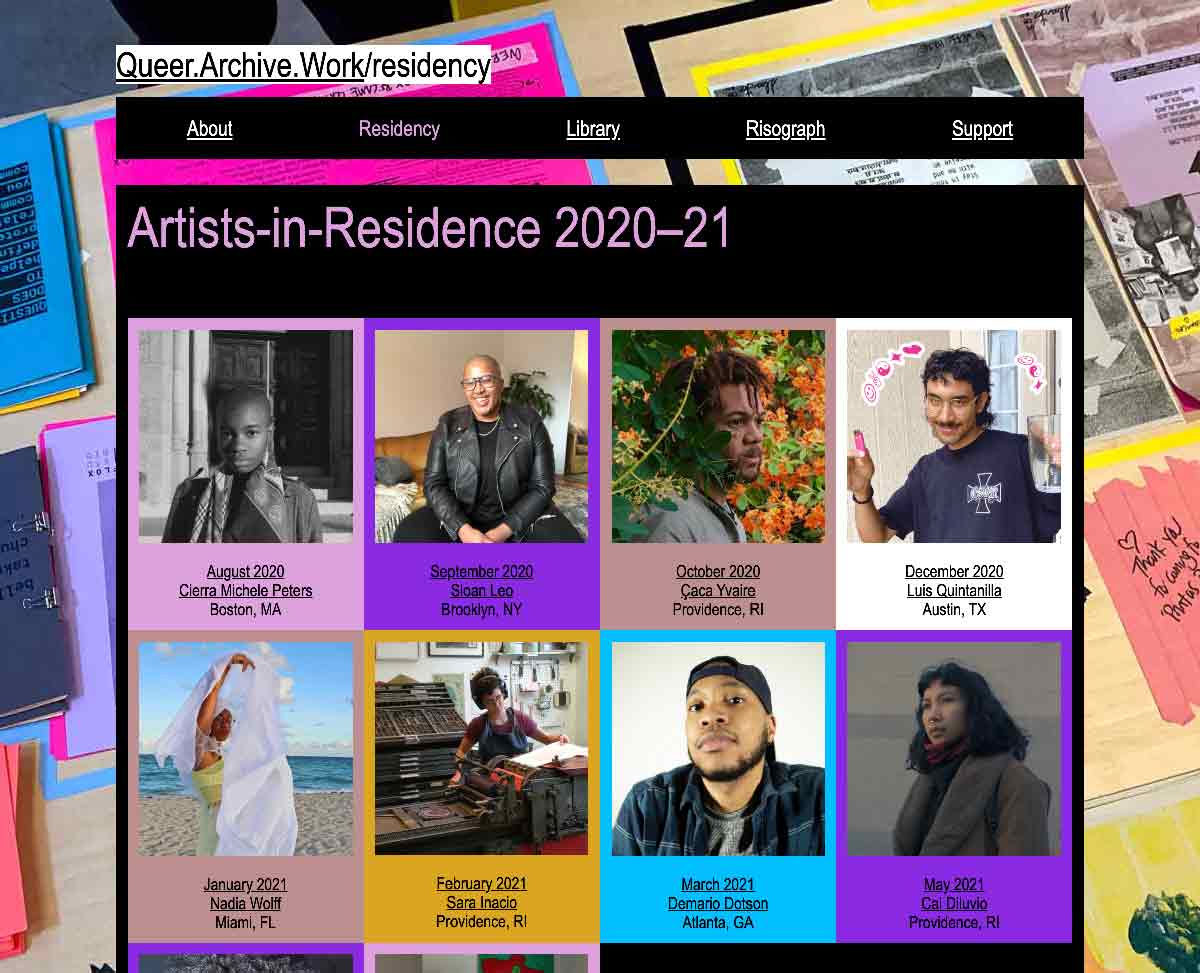

Queer.Archive.Work Artists-in-Residence 2020–21

QAW brings direct financial and creative support to artists through a risograph residency program. In 2020 we began hosting residents, both locally and from throughout the US. Each artist is granted the entire studio for their own use during a 2-week residency, along with supplies and cash funding to support their work.

17

URGENCY AS A SLOW, ONGOING COMMITMENT TO MAINTENANCE AND COMMUNAL CARE

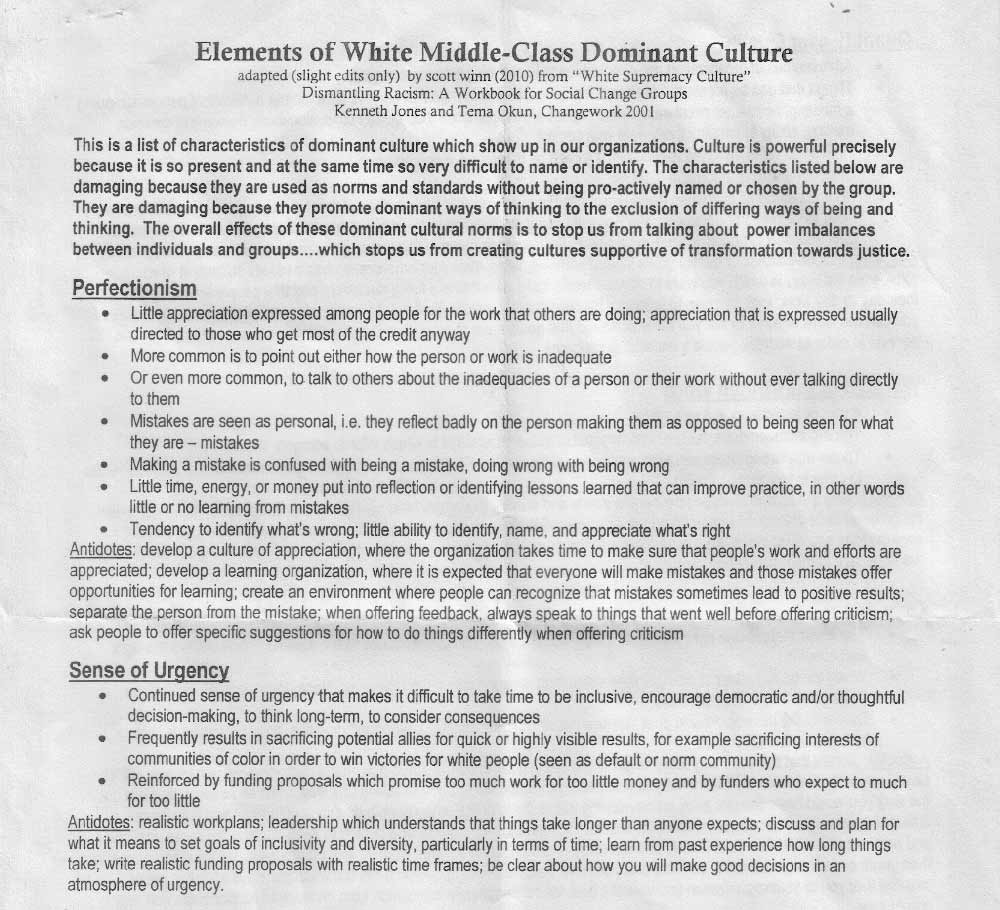

“Elements of White Middle-Class Dominant Culture,” (2001/2010) (PDF)

As a growing community, Queer.Archive.Work is learning about what it means to gather during distanced times, and how to create and sustain a genuine sense of connection on screen. Too often, urgency is used to exert pressure and power over a situation, online and within institutions that use speed and highly visible results as a form of gatekeeping, and as ways to inhibit thoughtful decision-making. We’re looking closely at how we use urgency as a specific concept in our collective publishing spaces—

Queer.Archive.Work community hang-out (November 2020)

—learning to slow down and to let things emerge, and to work at the speed of trust (adrienne maree brown). It’s most apparent in our steadily growing online community, where we meet casually on a weekly basis, and encourage each other to think counter-intuitively about urgency as a slow, ongoing commitment to maintenance and communal care.

18

URGENTCRAFT

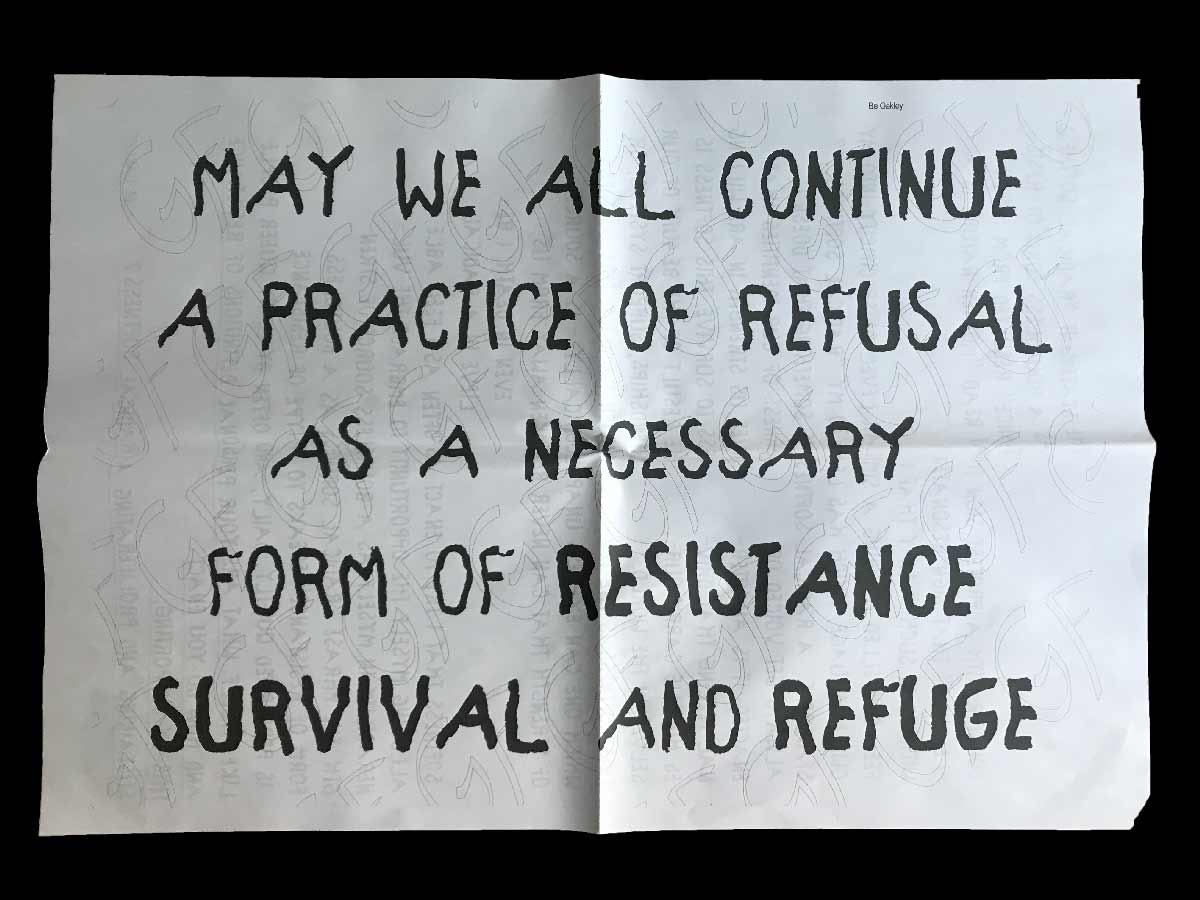

Be Oakley, Queer.Archive.Work #1 (2018)

After the incredible mess of 2020, I’m finding it helpful to circulate queer strategies of resistance and survival as a loose set of principles, within talks and writing and syllabi, like this one. Urgentcraft is about dismantling oppression-based ideologies and prioritizing anti-racism, justice, and liberation in our work. It’s about recognizing urgent artifacts as necessary acts of making public that gather and mobilize people around the potential for radical change. Urgentcraft exists outside of art and design worlds, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the ultimate smooth flow of design perfection and art world purity. It is not an aesthetic.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

19

A CALL TO ACTION

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. This is my own call to action, shared here in response to this sense of finality.

In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to us. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Commissioned by

post documenta: contemporary arts as territorial agencies

A cooperation between the Academy of Fine Arts Leipzig

and the Athens School of Fine Arts

Supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)

URGENTCRAFT

A NARRATIVE SYLLABUS IN 19 PARTS

PAUL SOULELLIS

JANUARY 2021