Federal agents confronting Black Lives Matter protesters in Portland, Oregon, July 20, 2020. Credit: Noah Berger/Associated Press

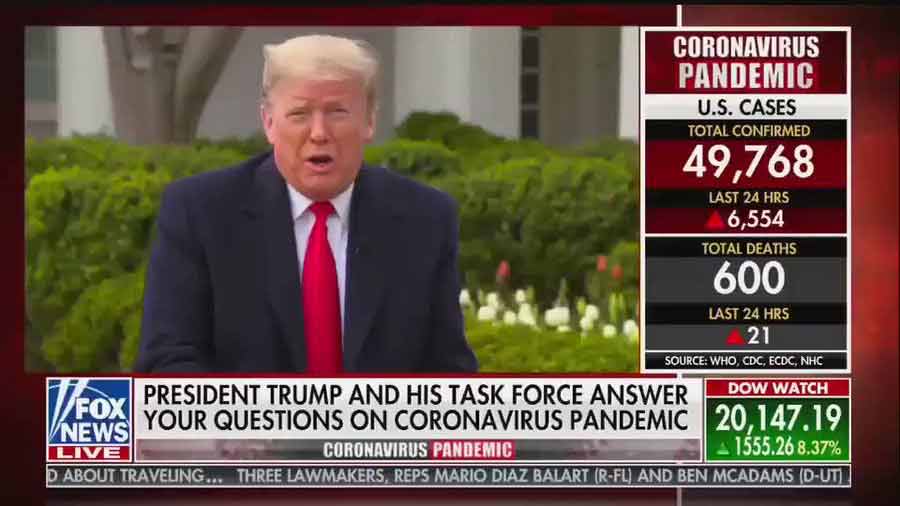

We’re more than half a year into the pandemic and I’ve finally stopped counting my days in quarantine. As our new normal keeps shifting, I’ve come to realize that there is no one number or headline or photograph powerful enough to completely represent our collective crisis right now, or the extent of the damage being done by the absence of leadership and necropolitics of our time.

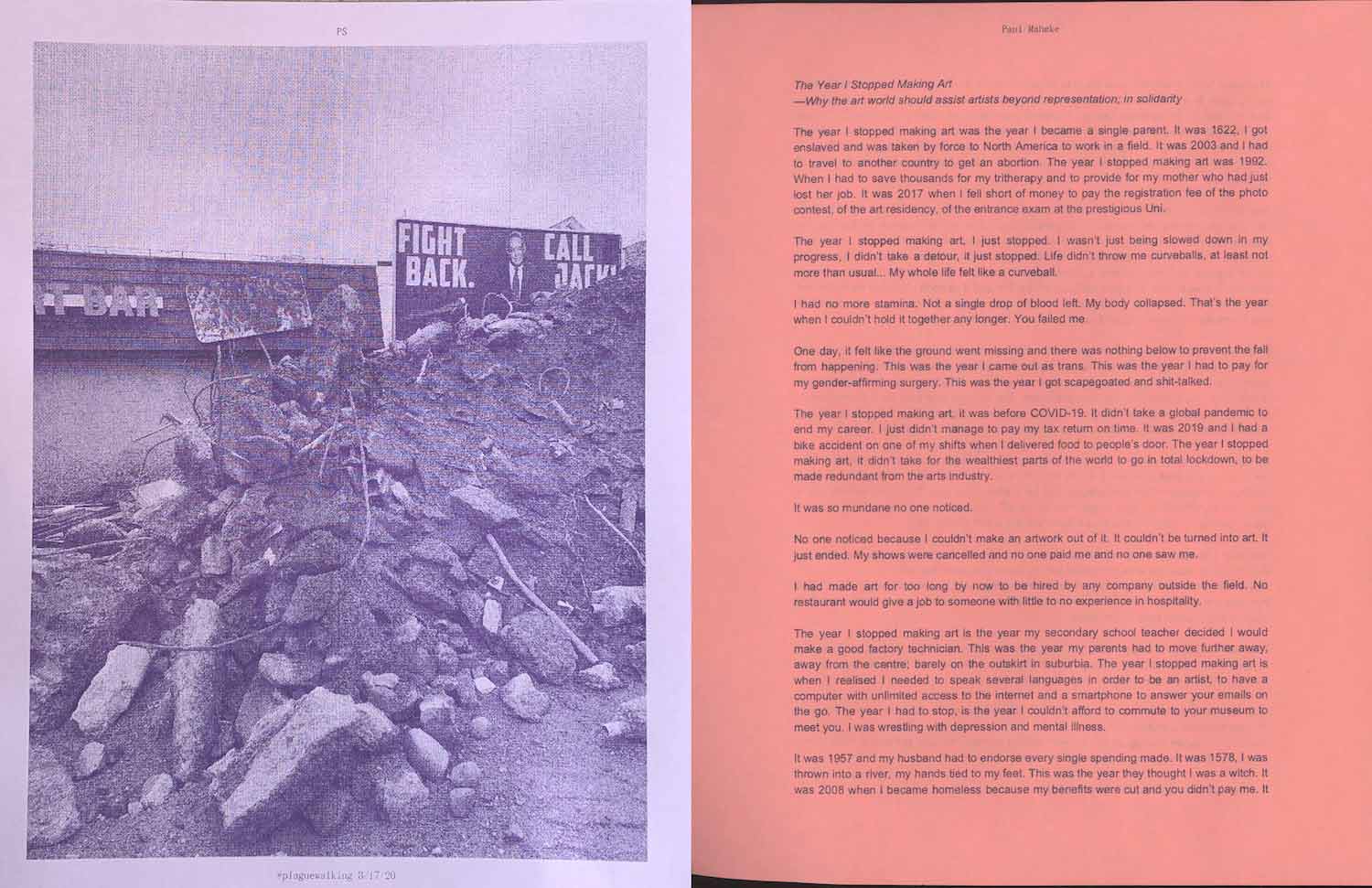

Death-Dow watch, March 29, 2020

And while we are surrounded by data, there is no metric detailed or accurate enough to measure the depth of structural failure we’re collectively witnessing right now, or the complexity of intersecting crises that these failures continue to produce, compounded daily, throughout the world.

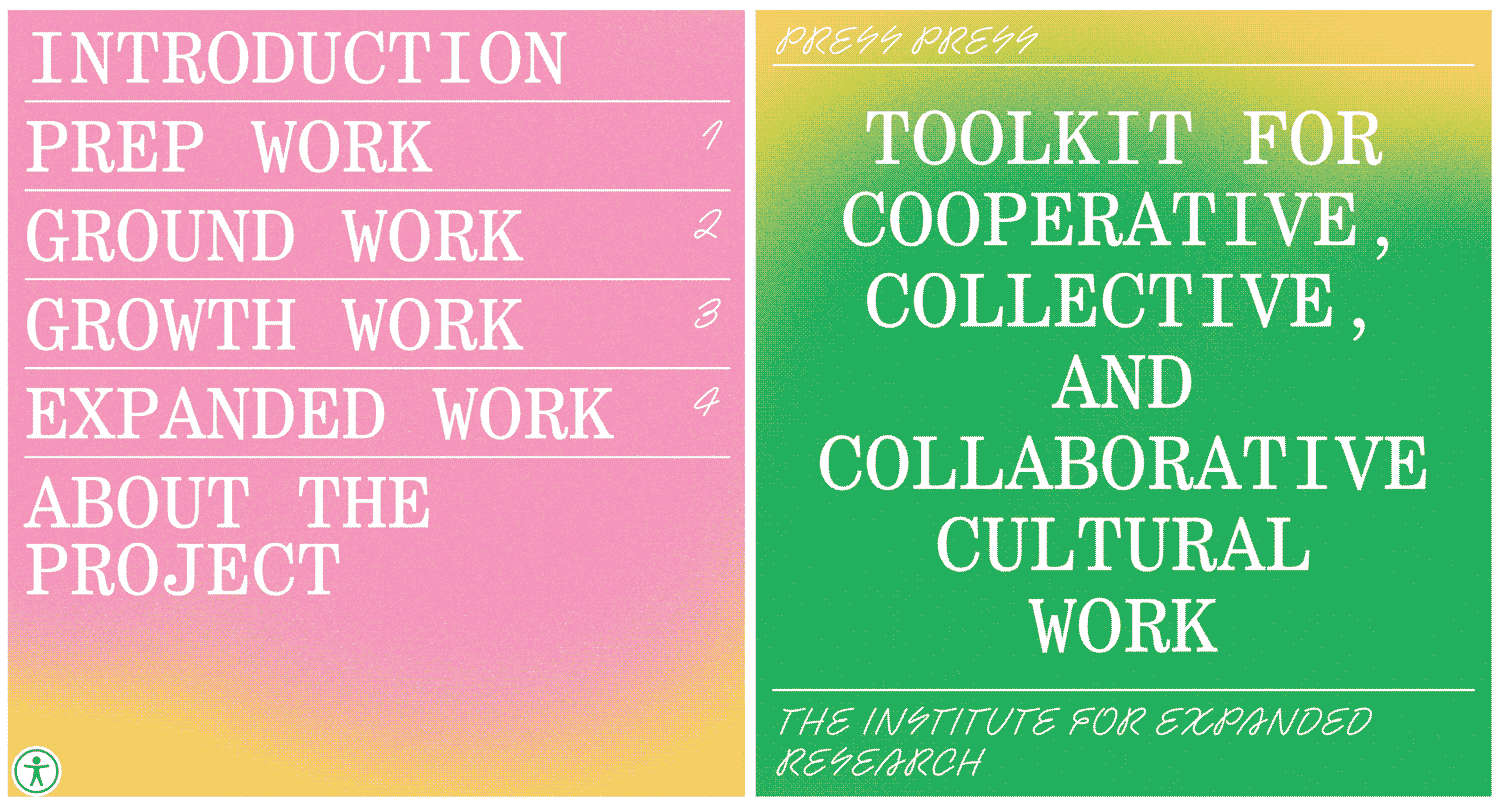

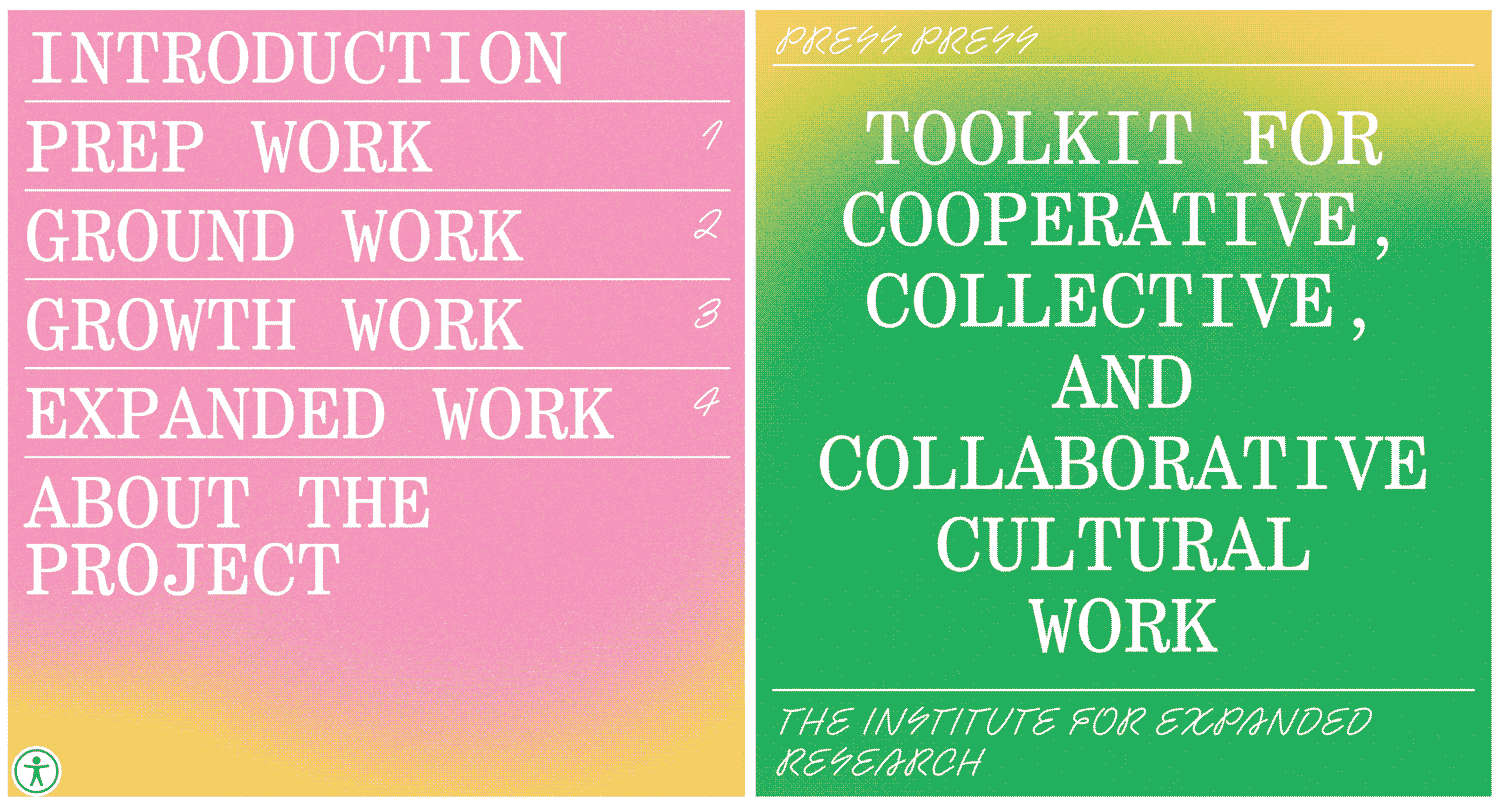

Press Press, toolkit.press

I will talk about how I’ve been working, and what I’ve been doing in 2020, but first I’ll approach that work through some of the values that I’m prioritizing right now, as an artist-publisher, as an educator, as someone who is trying to support the radical work that I see happening around me, in response to these intersecting crises.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, streamed live on July 9, 2020

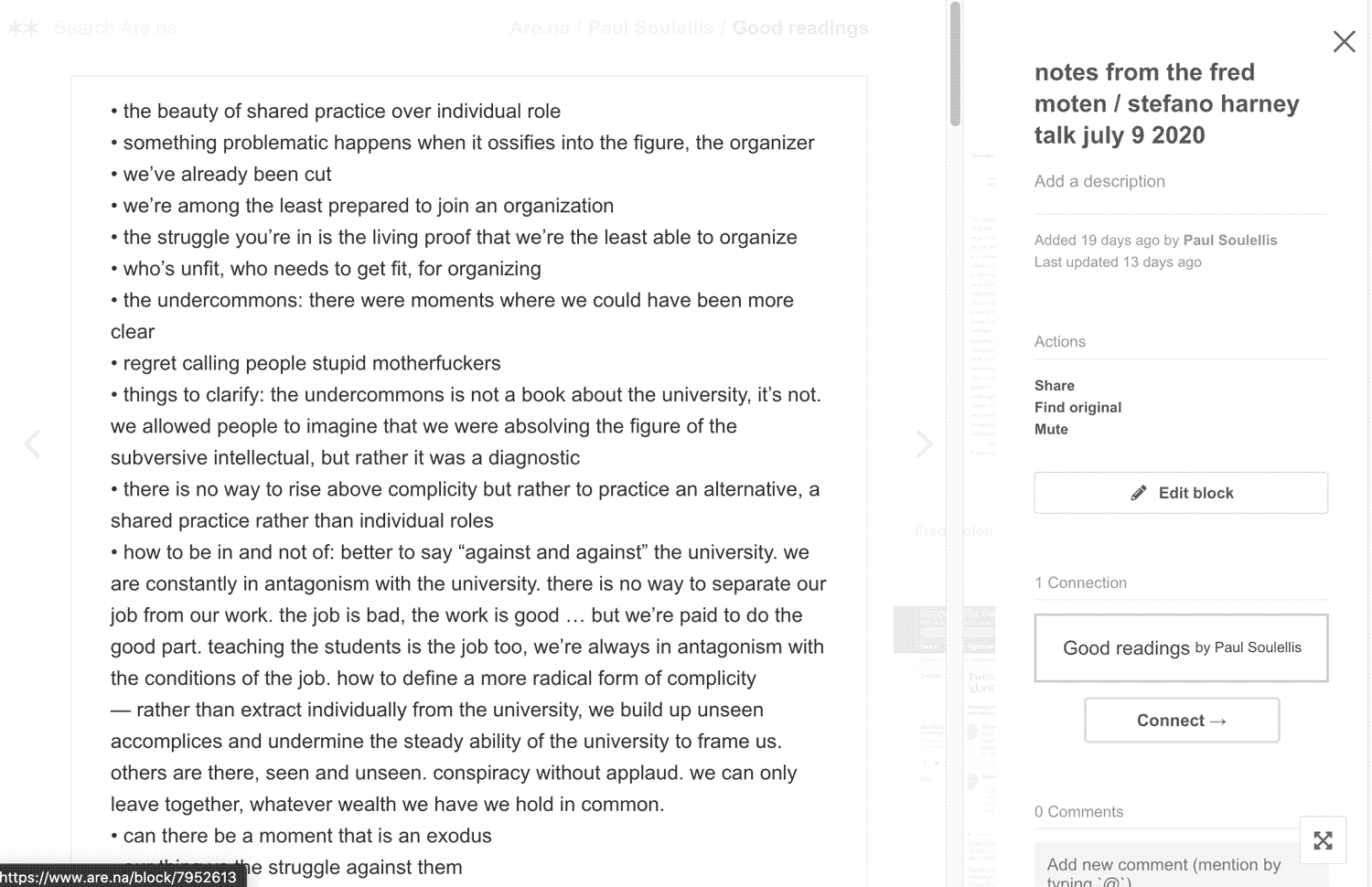

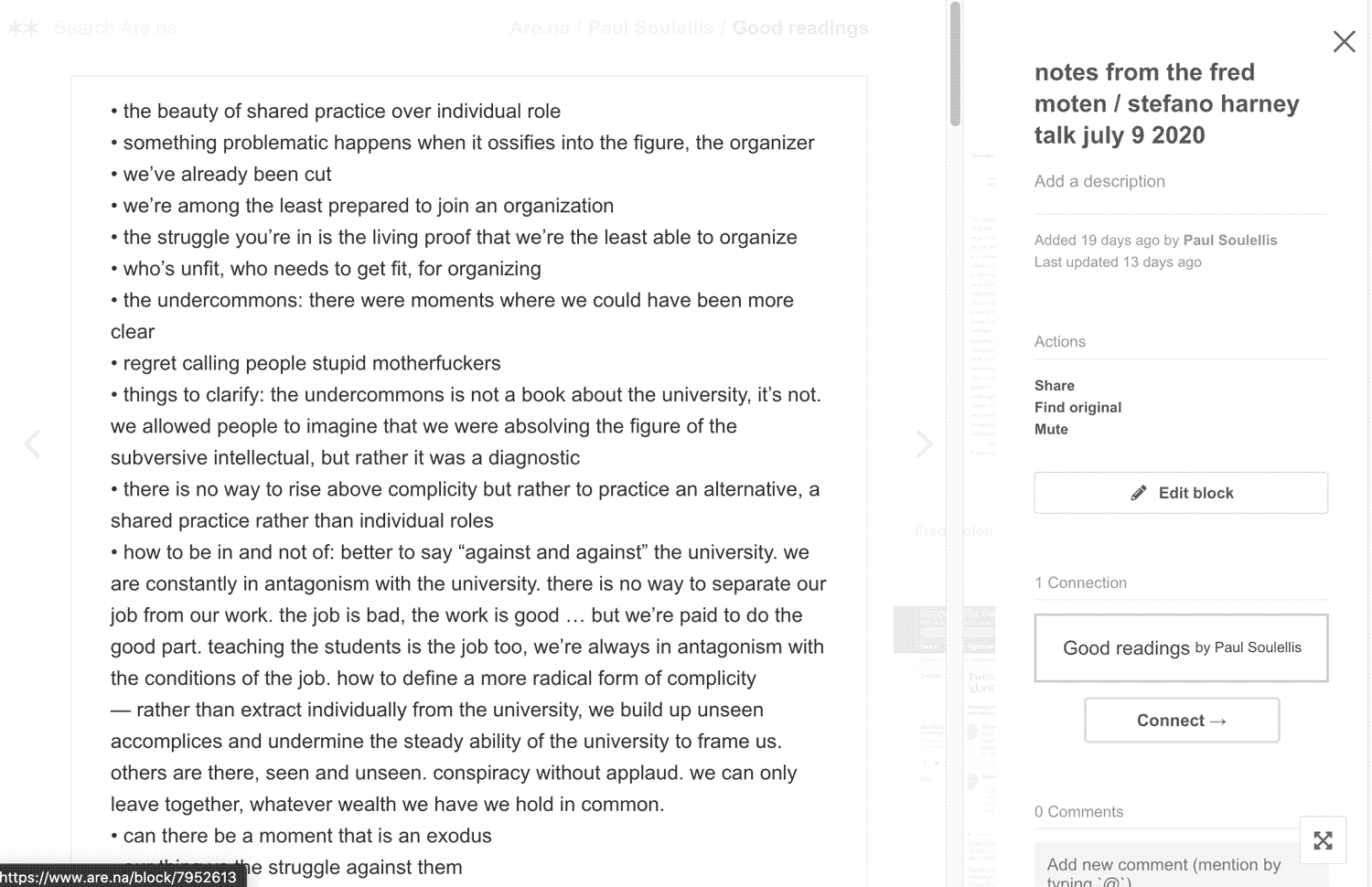

Recently, I was able to tune into a talk by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, who were discussing their new text “the university: last words,” which is in part a response to their classic work “The University and the Undercommons” (2004). A lot was covered in this discussion, but the phrase I keep coming back to and thinking about is shared practice.

Michael Rock, Designer as Author (1996)

In the talk, Dr. Moten speaks about the beauty of shared practice over individual roles, and I’ve been thinking about what this might mean specifically in the context of art and design schools, where we’ve been taught, and where we continue to teach, at least where I teach, about the transformative power of individual expression. The power of the artist or the designer as author, and the values that naturally go along with this successful figure: ambition, competition, profit, ownership, self-sufficiency, and domination.

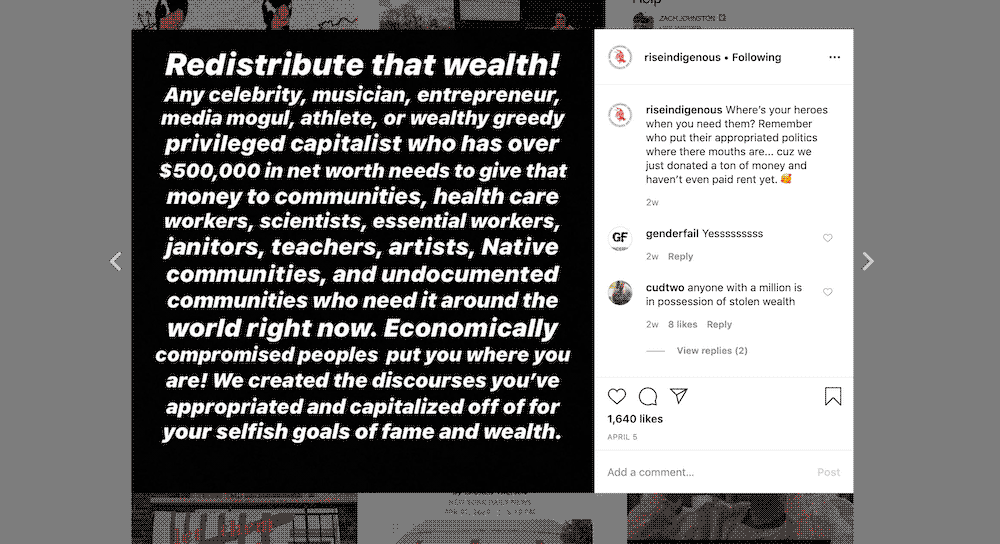

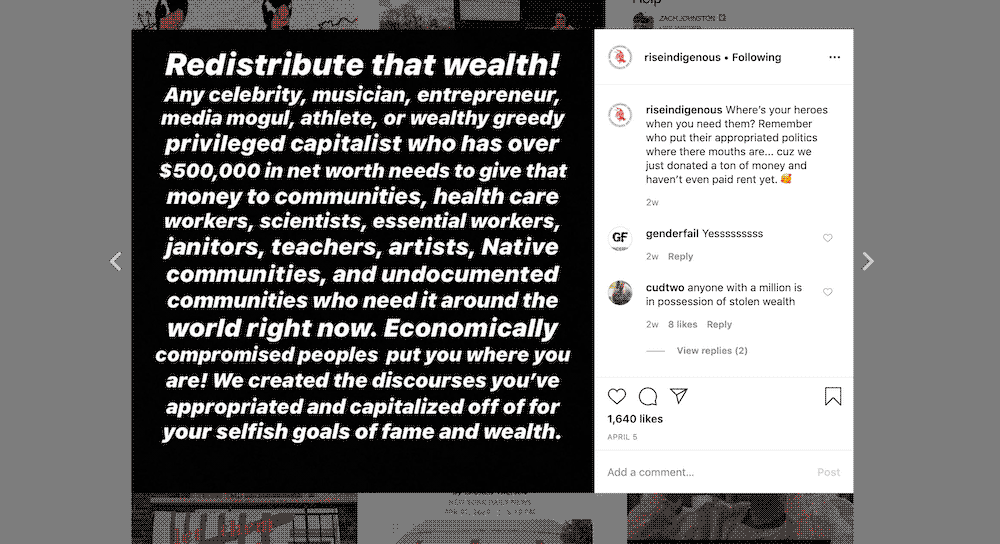

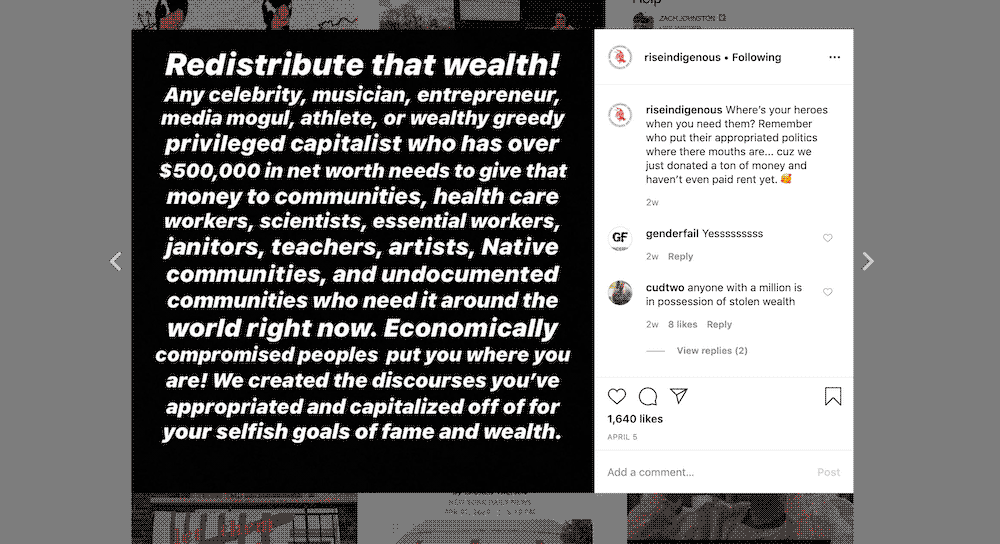

R.I.S.E. Indigenous, 4/5/20

We have no choice but to teach these values because they’re deeply embedded within these imperial institutions, keeping alive the promise of professional success, a promise that’s designed to drive everyone towards the same goal: the credential. A degree, be it a BFA or an MFA or a PhD, and the power that degree gives not just to participate in capitalism but to accelerate within it and reproduce its violence.

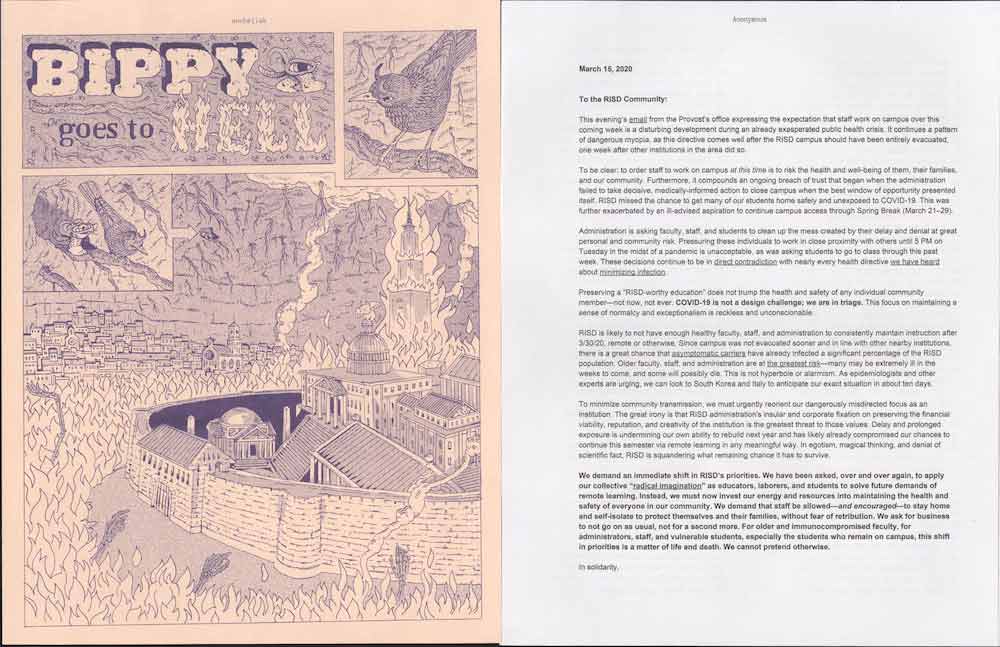

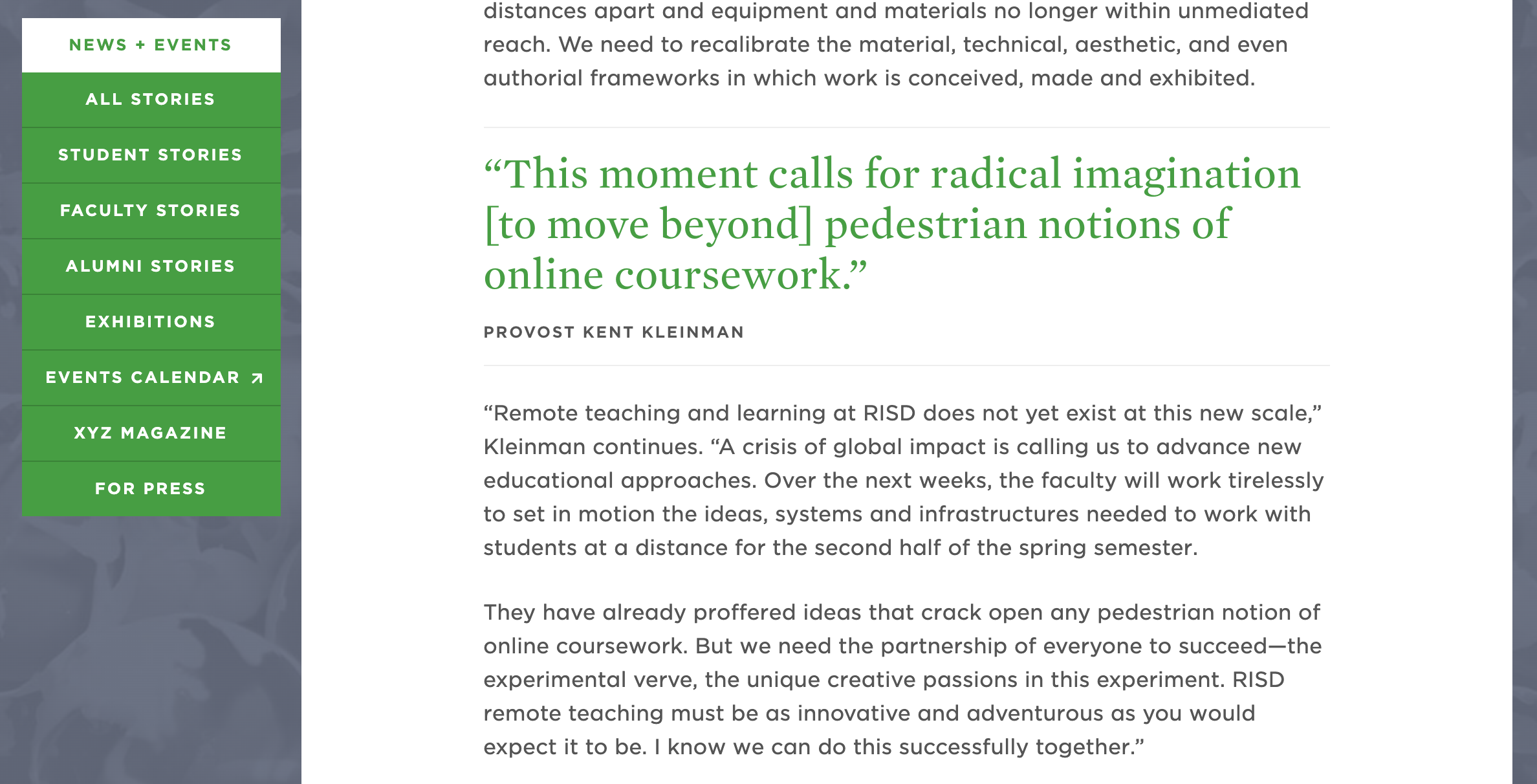

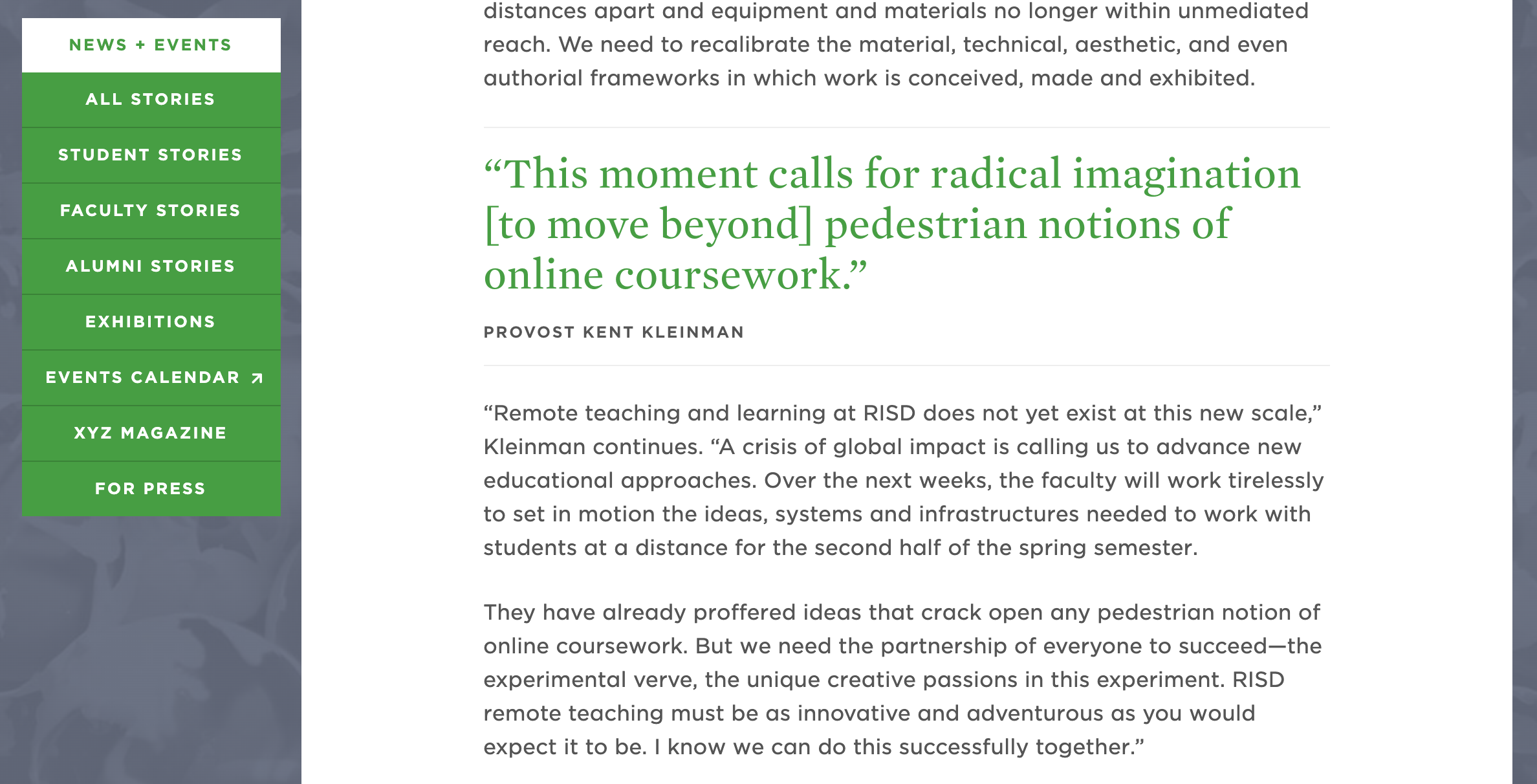

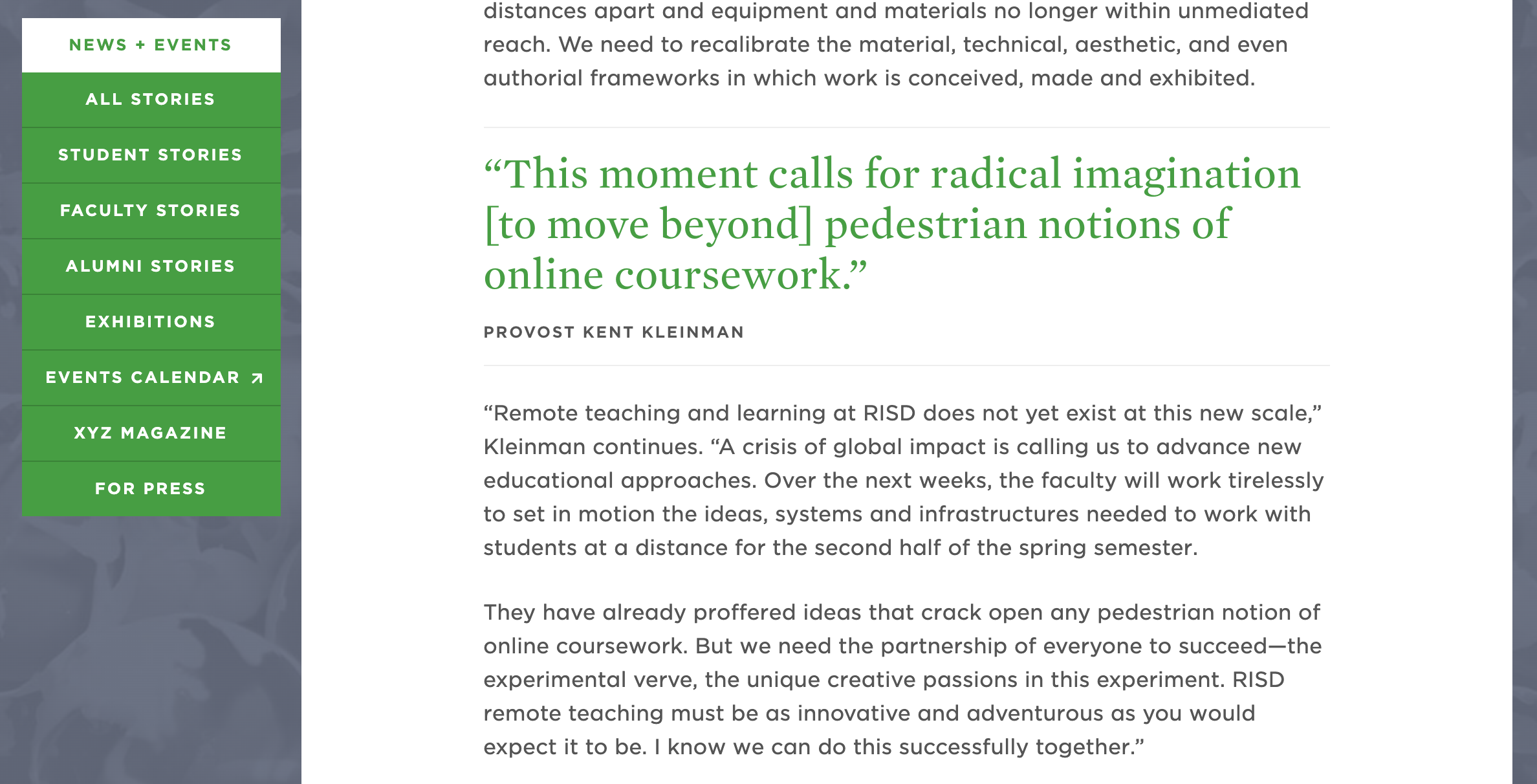

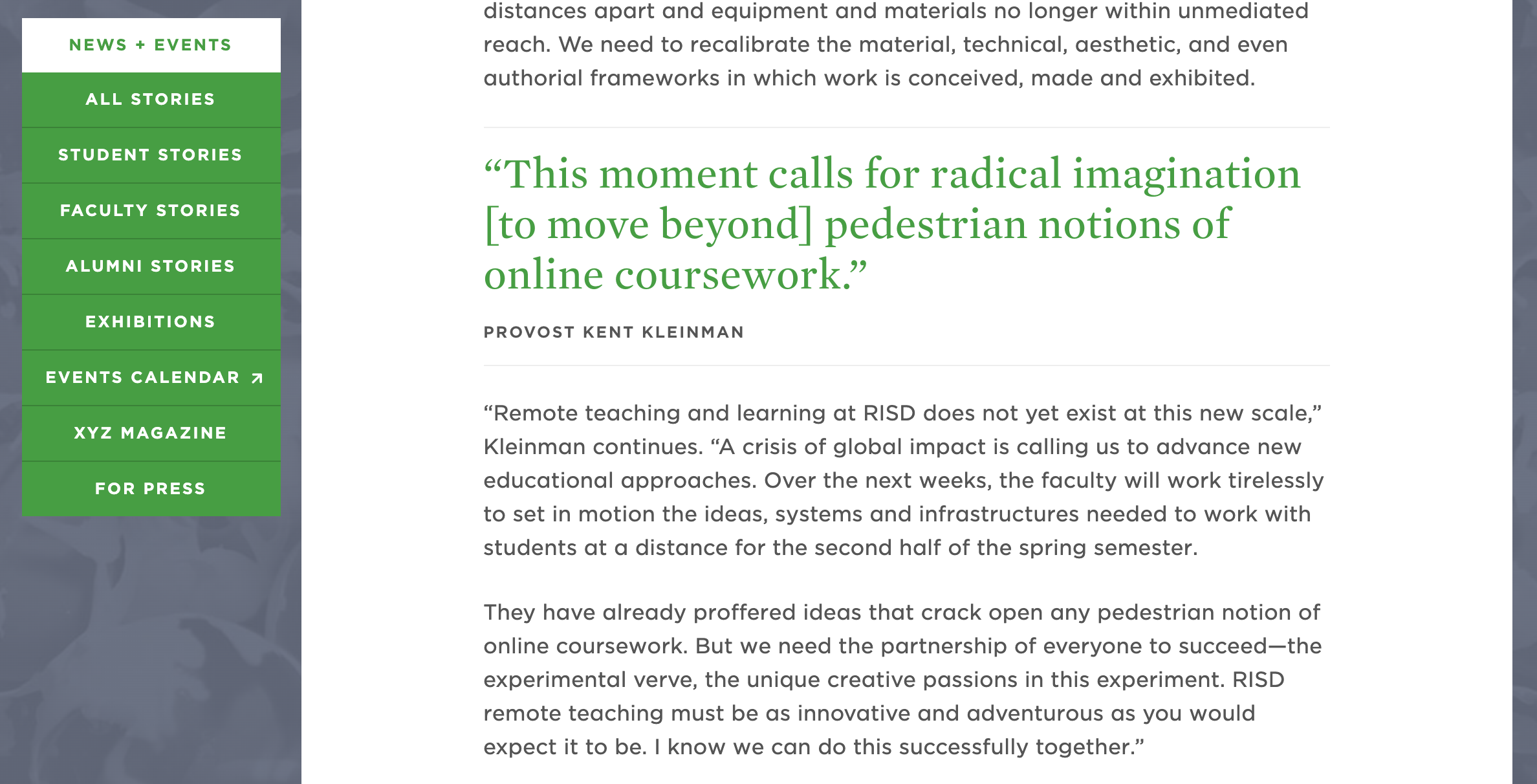

RISD’s call for “radical imagination” within its COVID-19 remote learning announcement, 3/15/20

In our teaching, we prioritize this value of exceptionalism because it’s required by the extractive practices of the art and design worlds. Ultimately, students learn that to be successful is to be sovereign—a supreme, independent power without any need to depend upon anyone or anything, be it kin or community or state, unless it’s for profit.

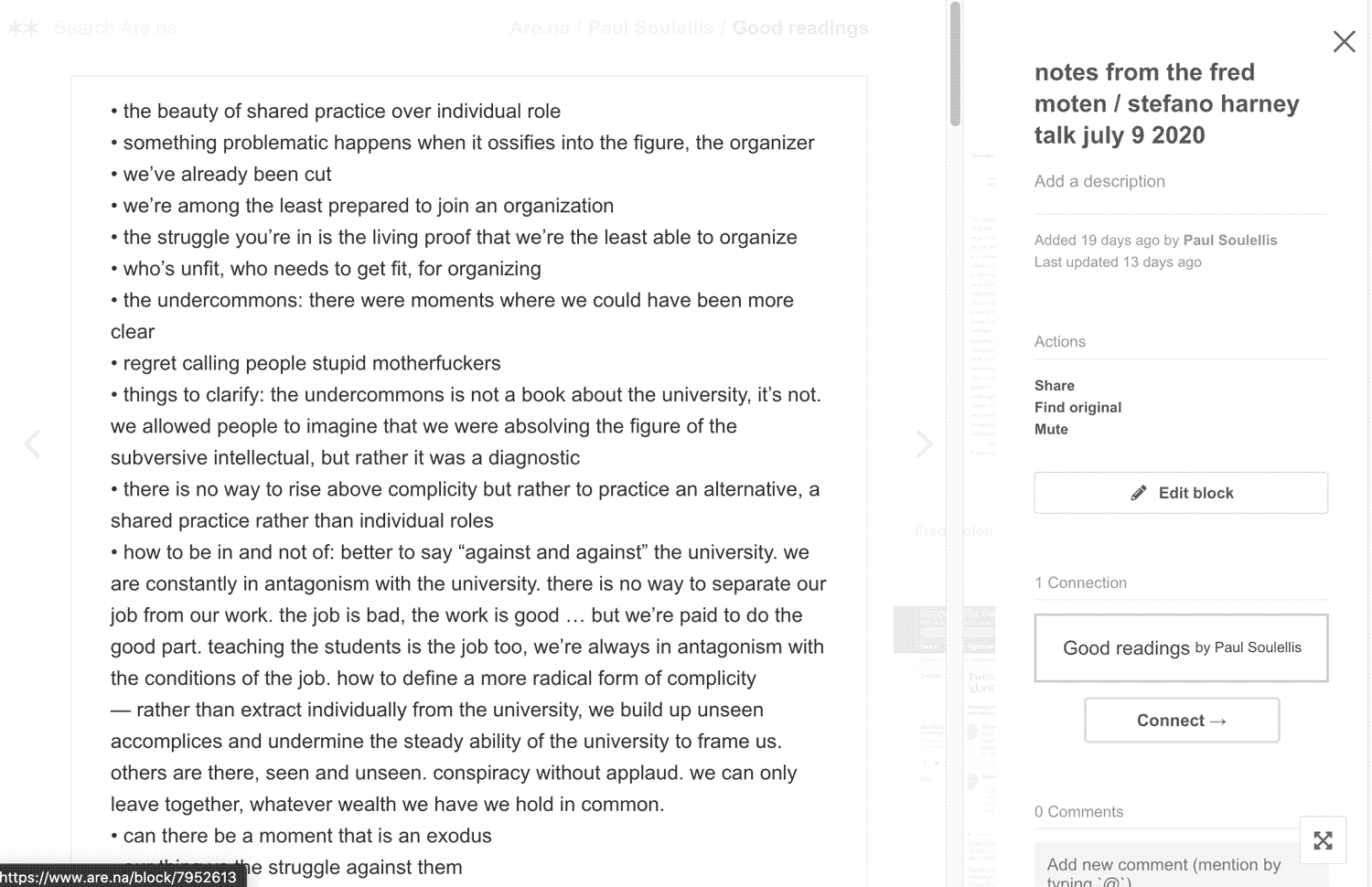

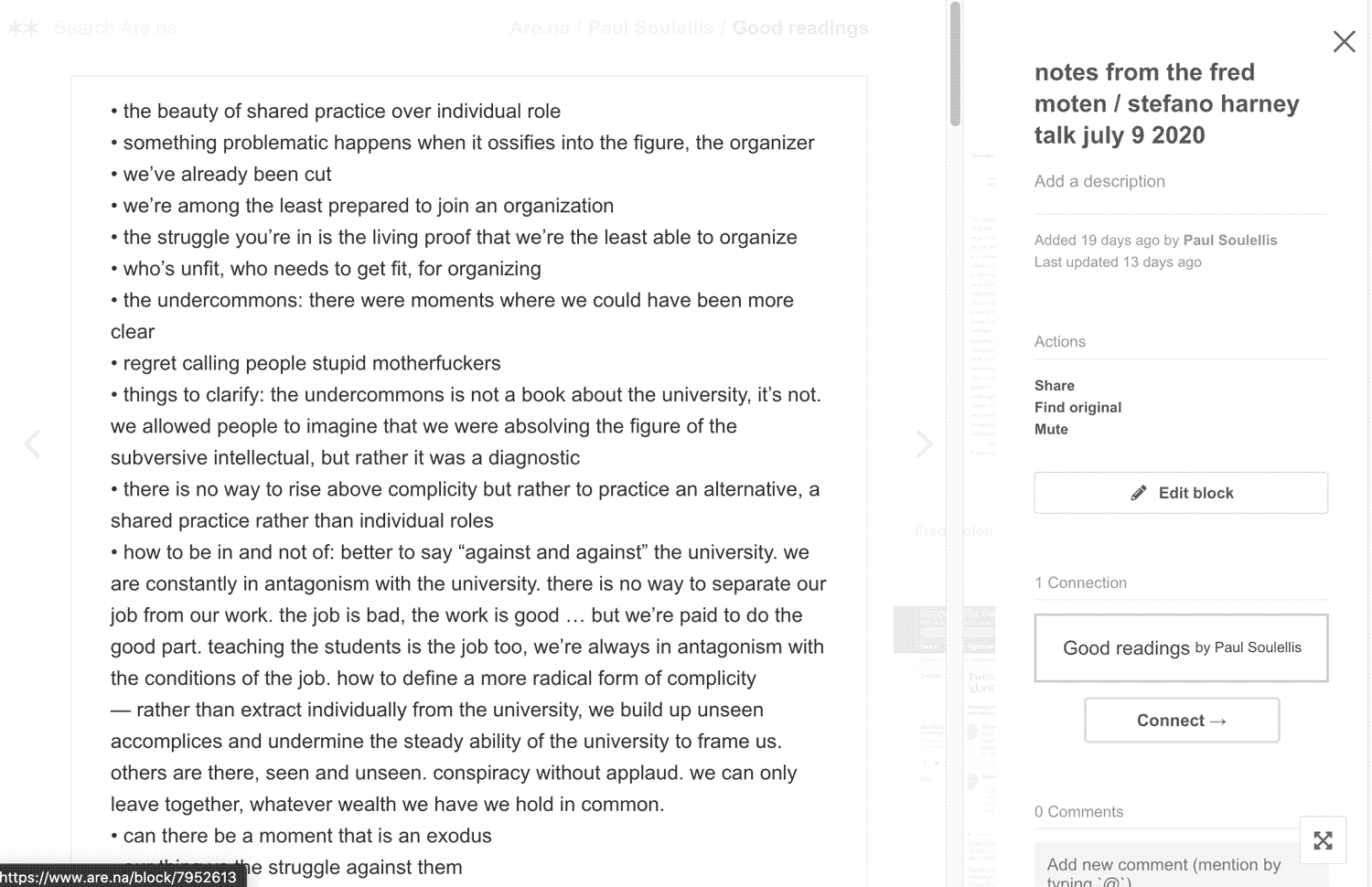

PS notes, Fred Moten & Stefano Harney talk, July 9, 2020

Instead, what would it look like to teach, as Dr. Moten said, “the shared practice of fulfilling needs together as a kind of wealth—distinguishing and cultivating the wealth of our needs, rather than imagining that it’s possible to eliminate them.” This resonates deeply with me right now, and it challenges me to pivot my own practice, away from the institution: towards collective work, radical un-learning, the redistribution of resources, and communal care. From my work ---->>> to our work.

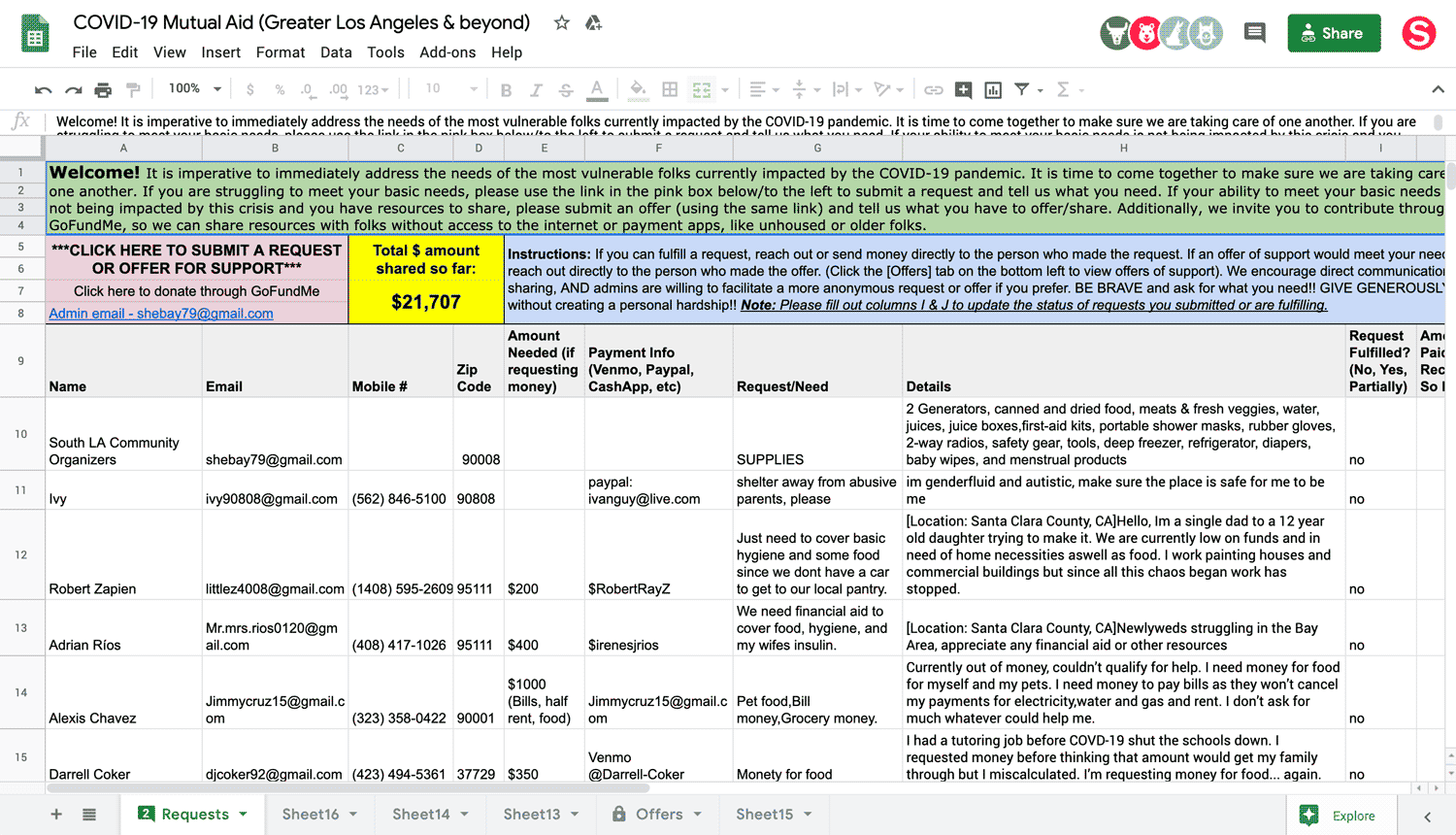

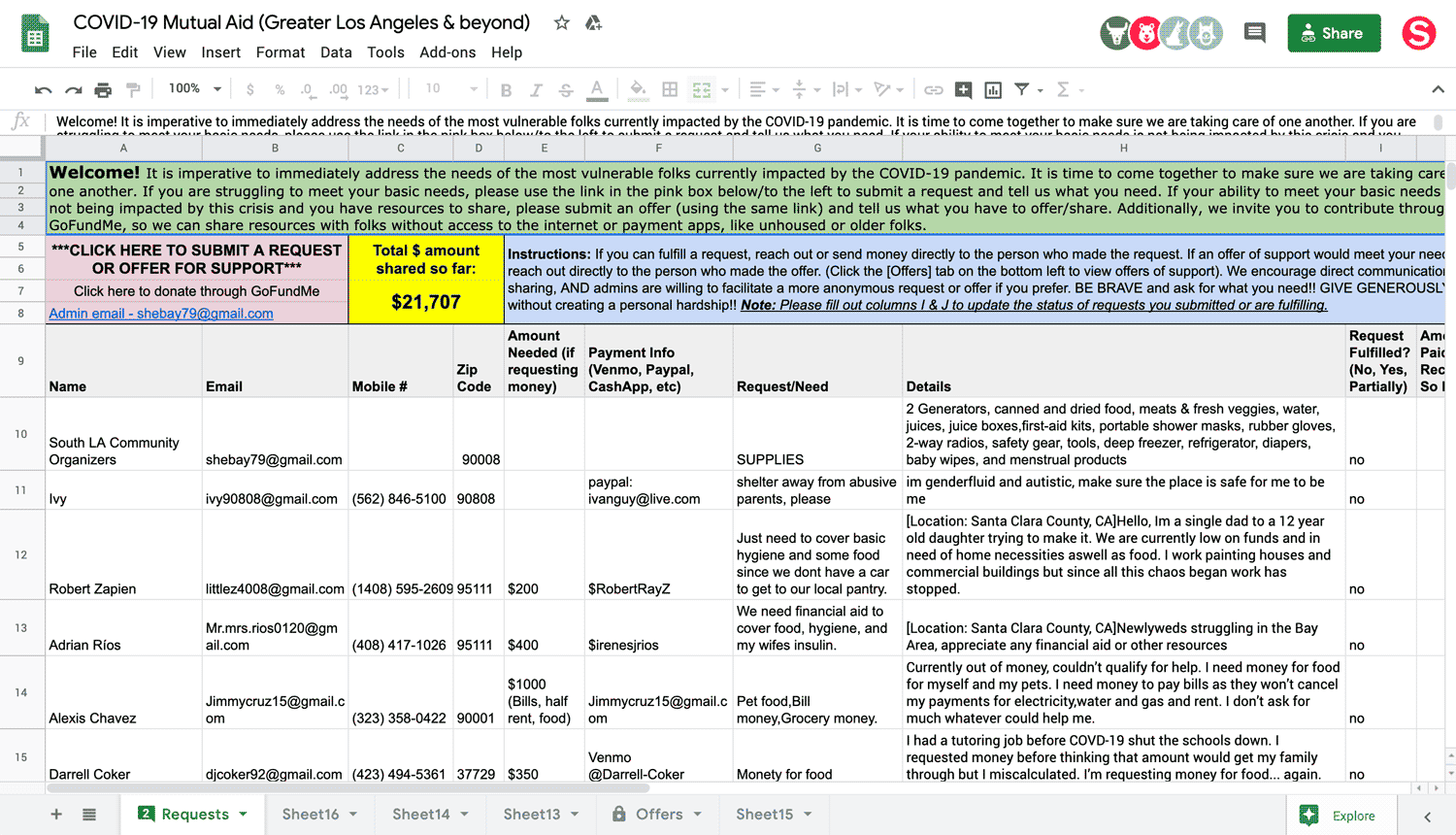

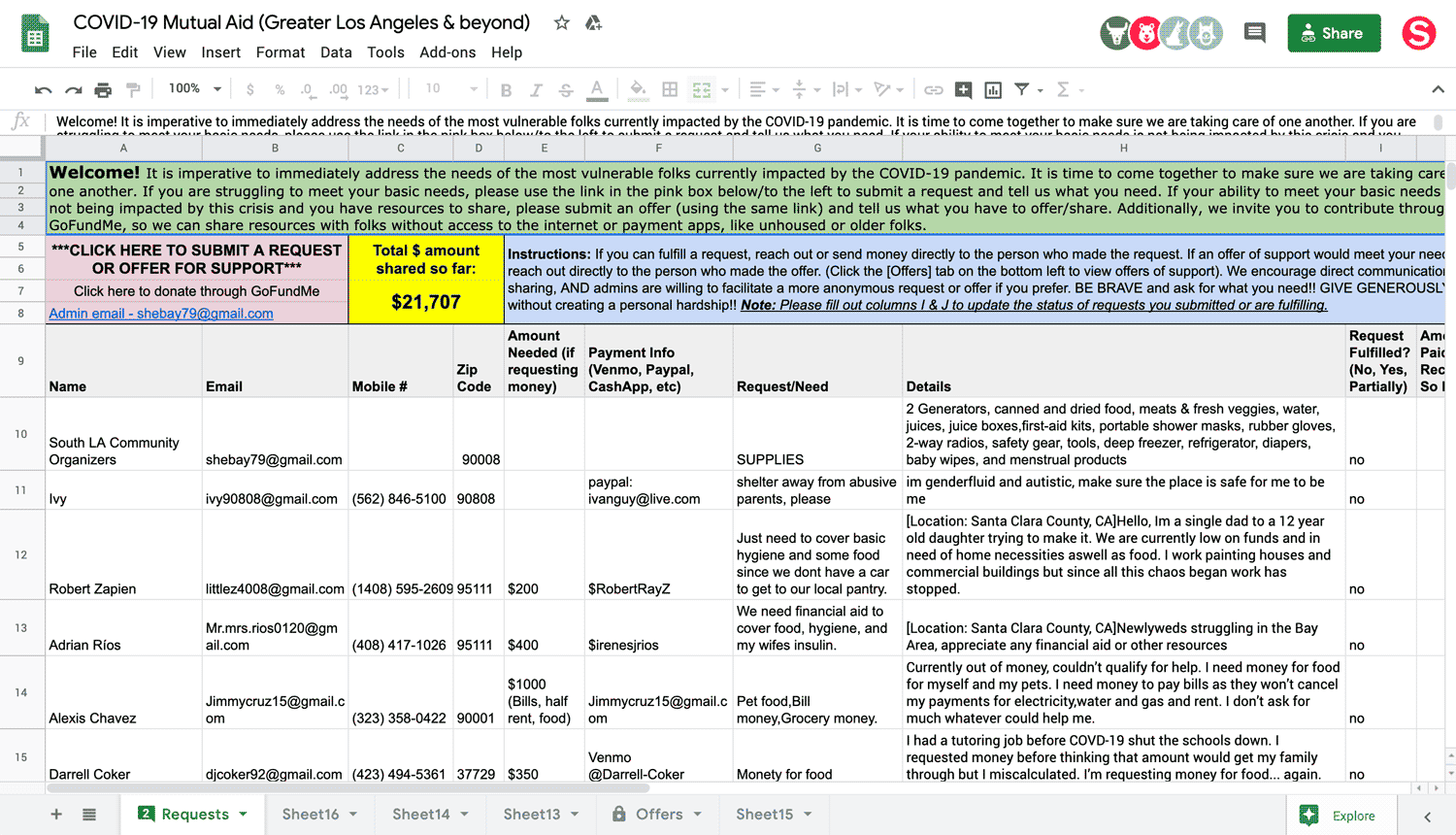

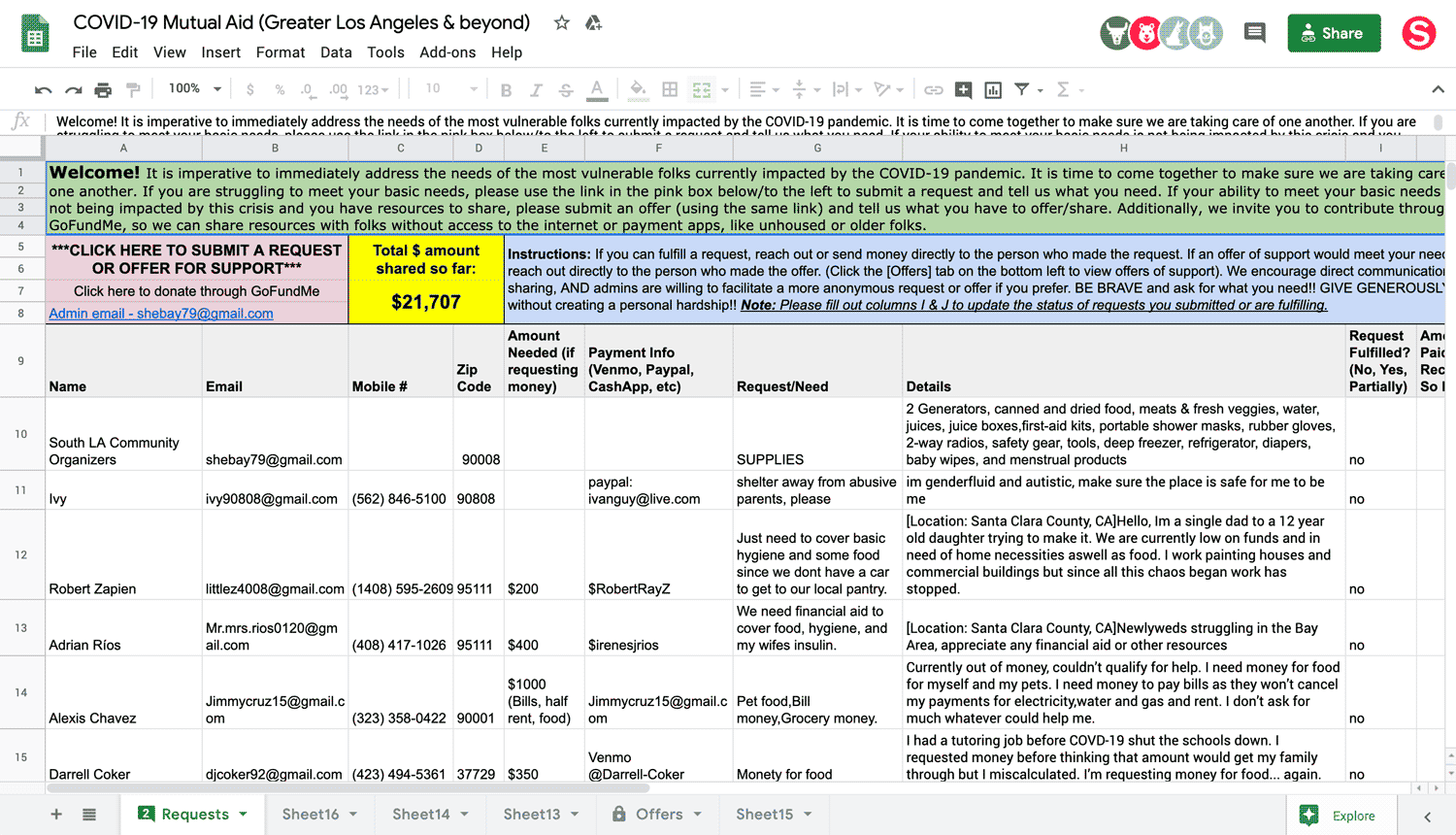

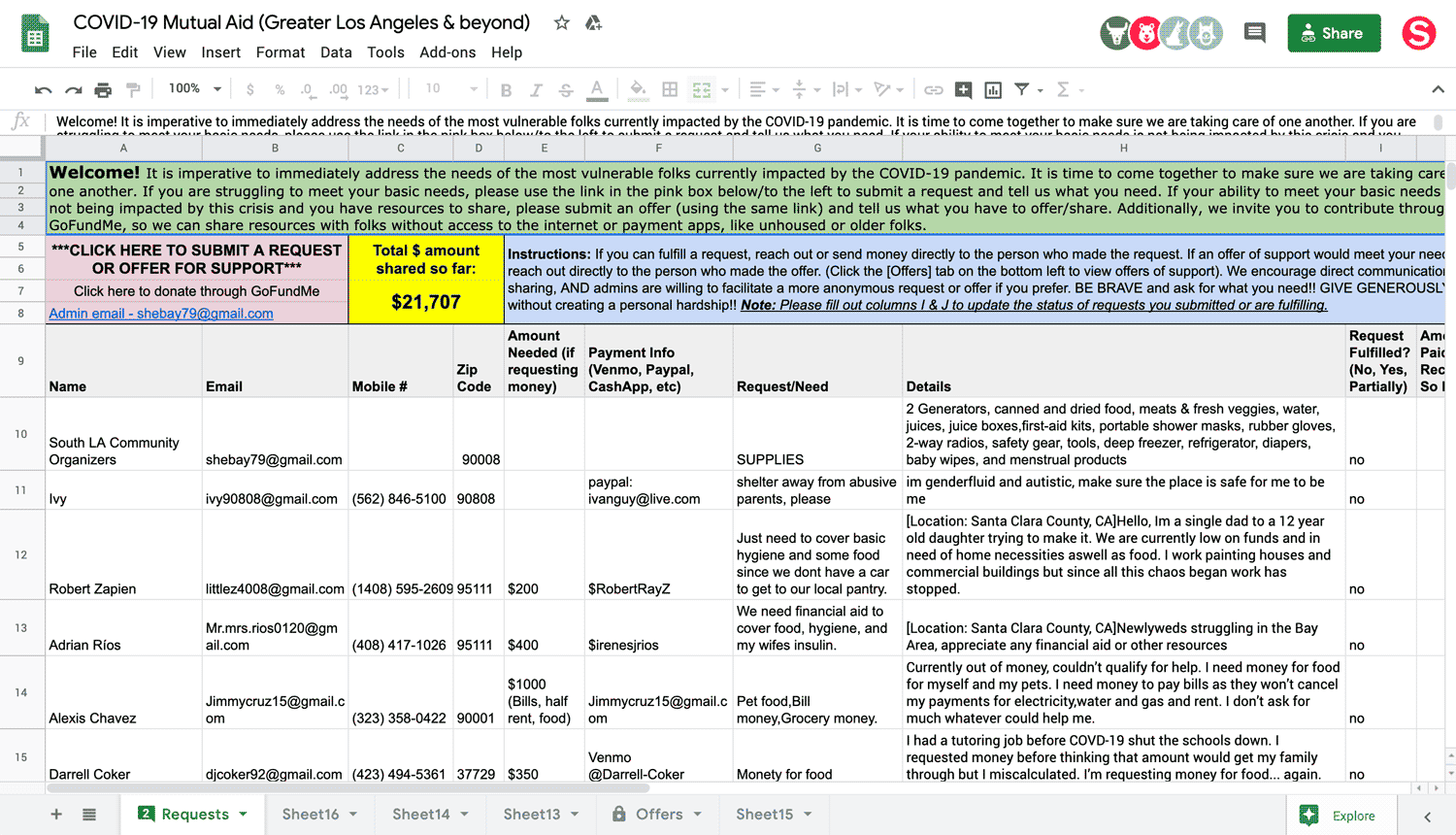

COVID-19 Mutual Aid (Greater Los Angeles and beyond), Google Doc, March 2020

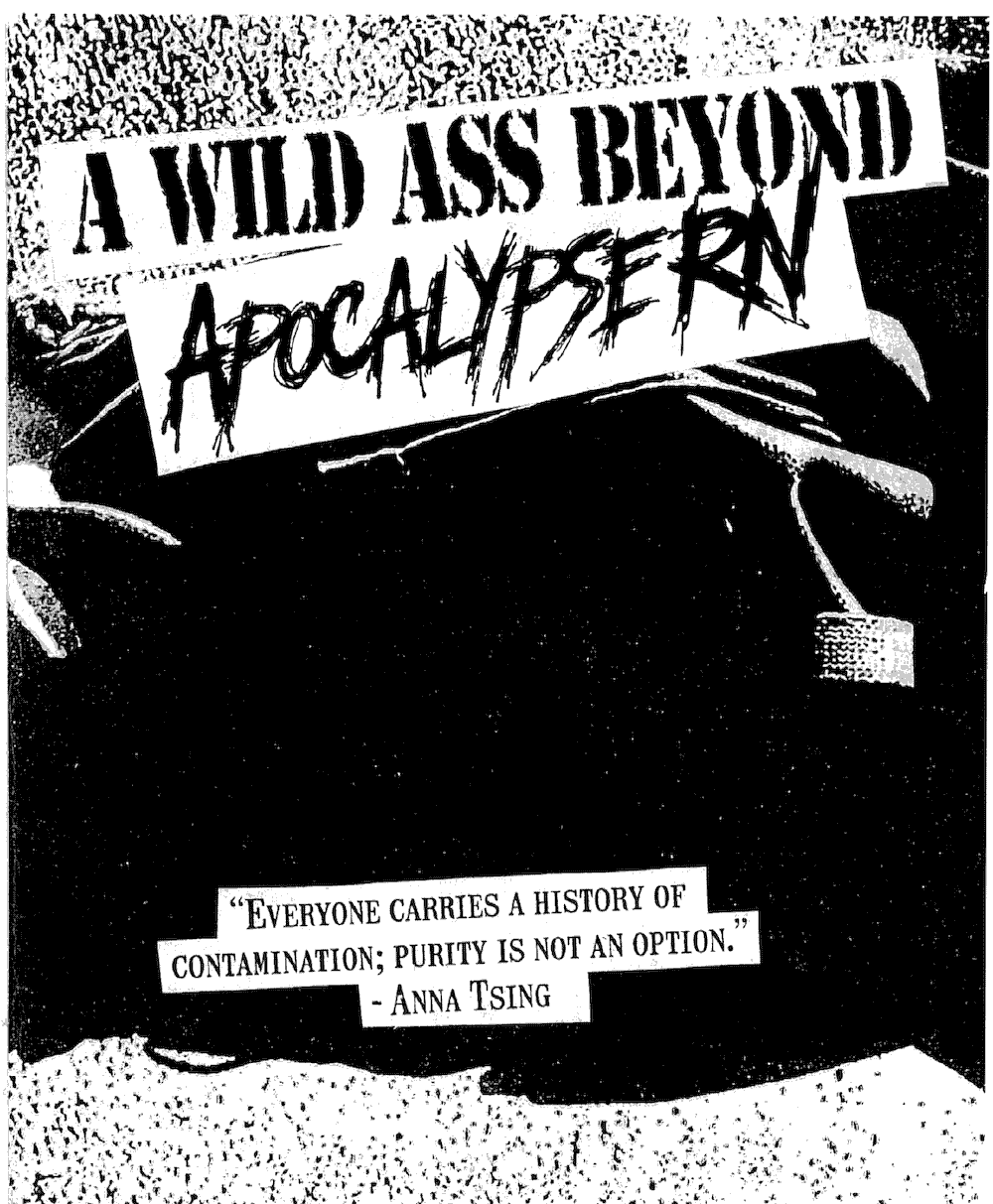

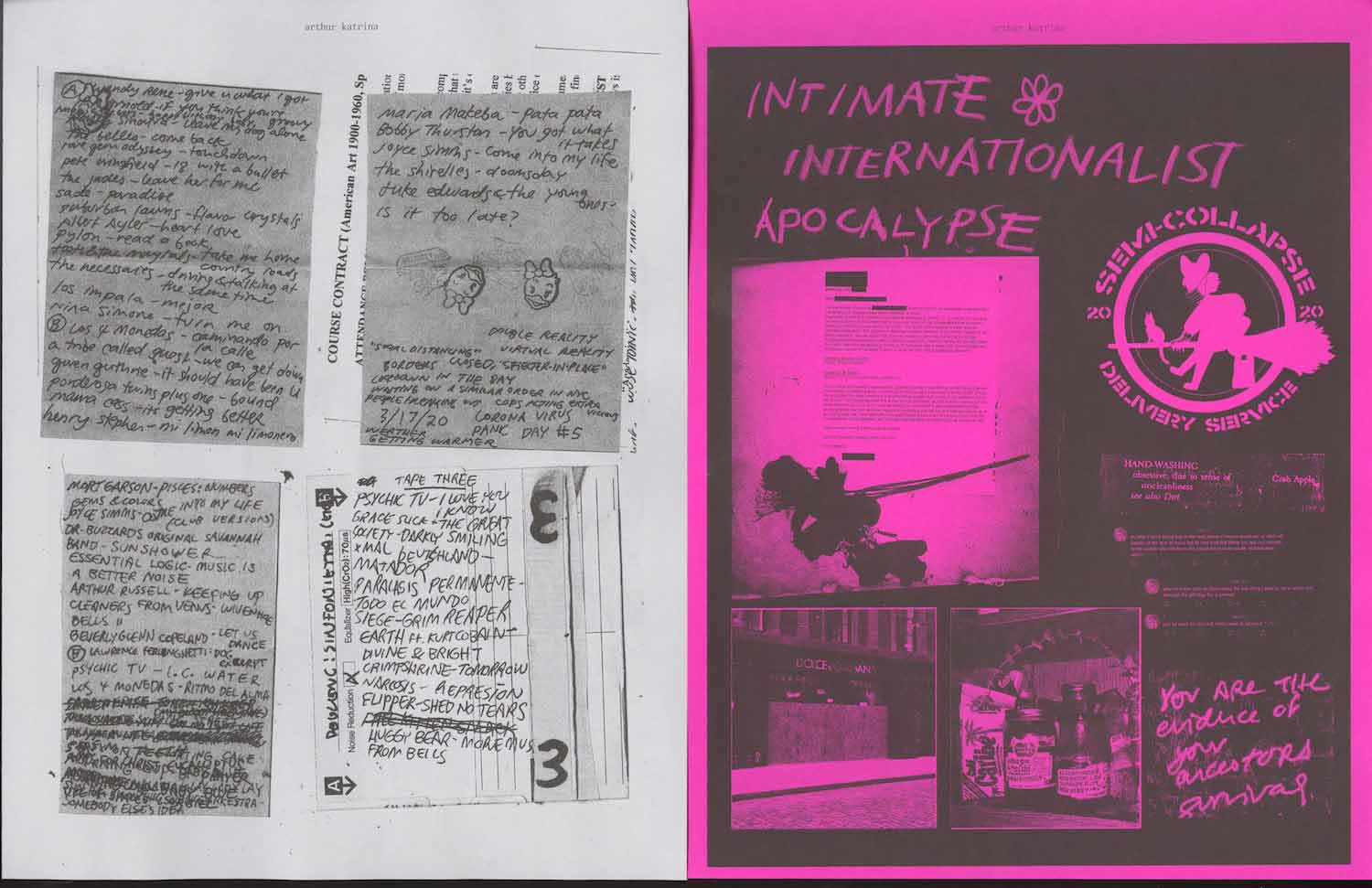

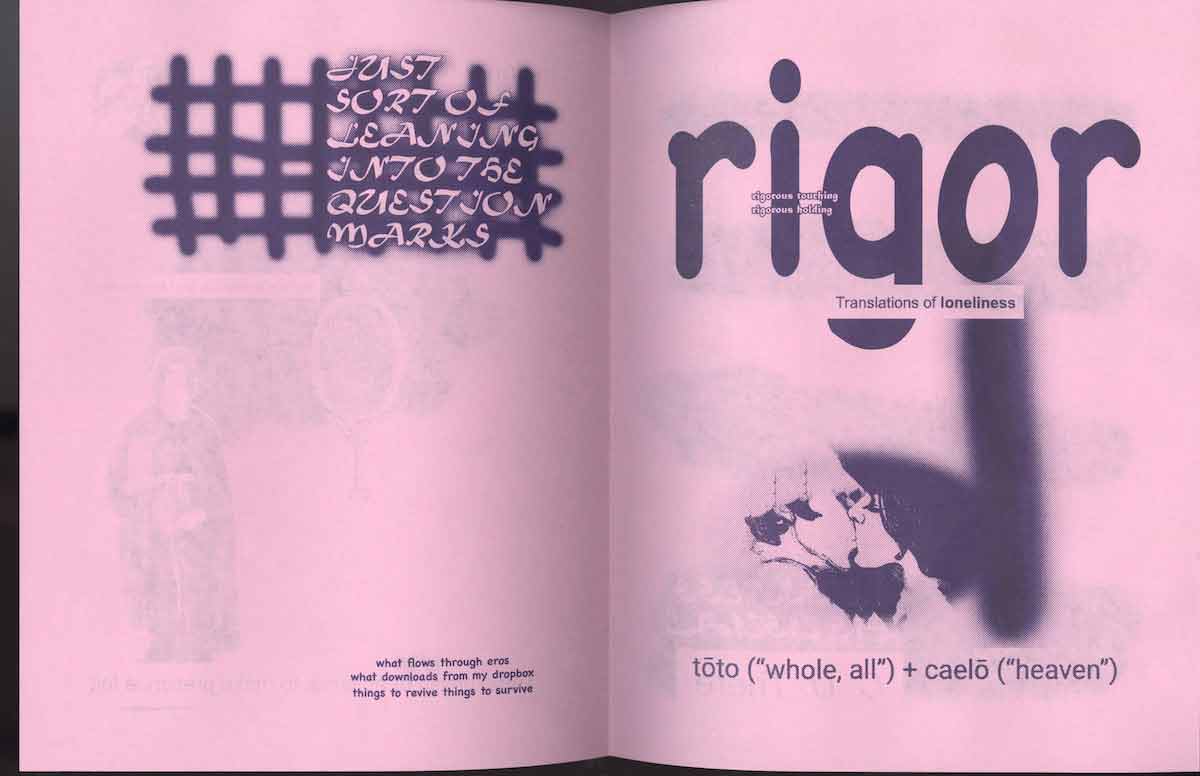

When I look back at so many urgent artifacts produced this year in crisis, the more powerful ones operate in this realm of shared practice. These are artifacts that step away from individual authorship, towards something larger—collective, cooperative works emerging from the shared wealth of needs.

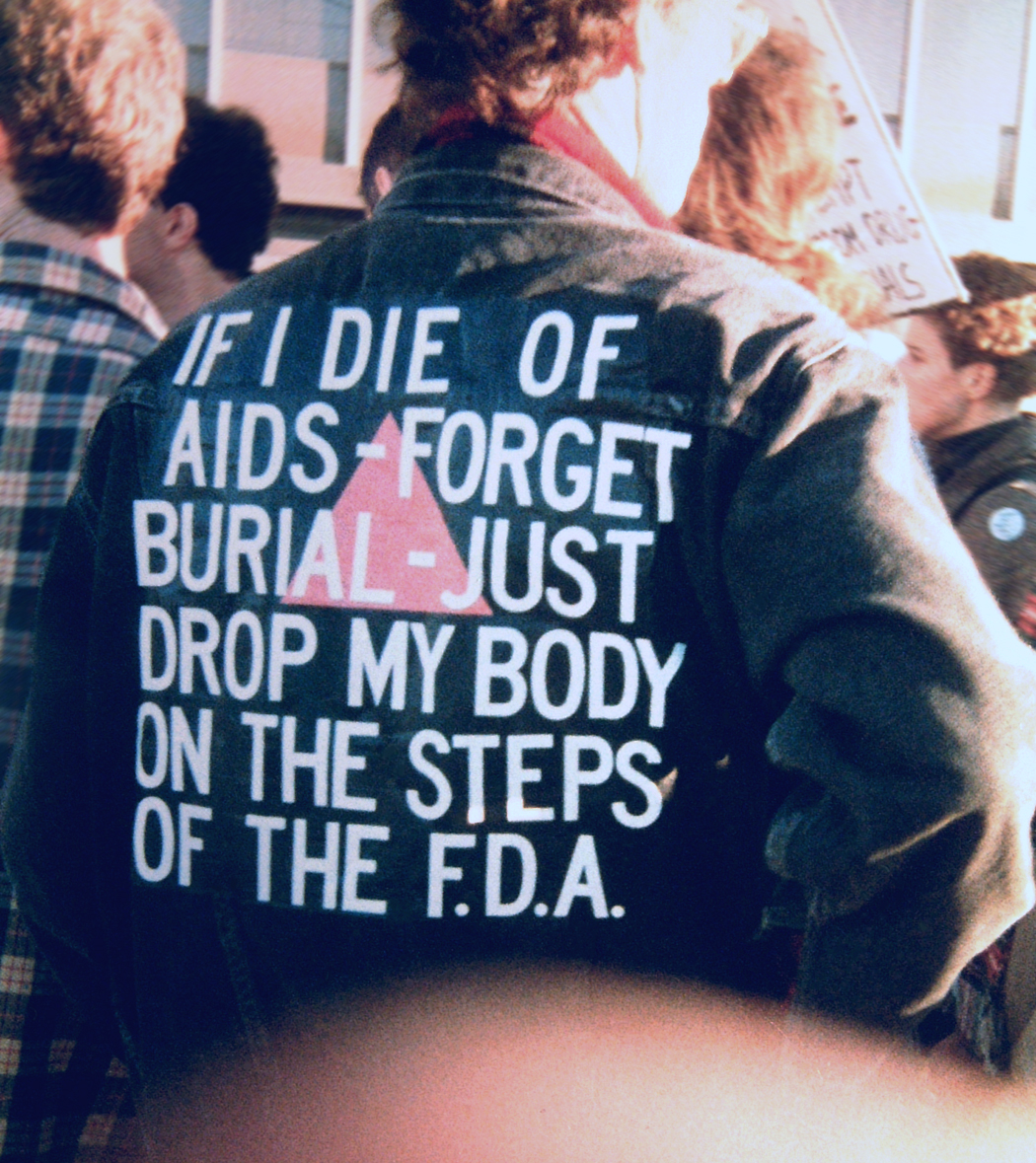

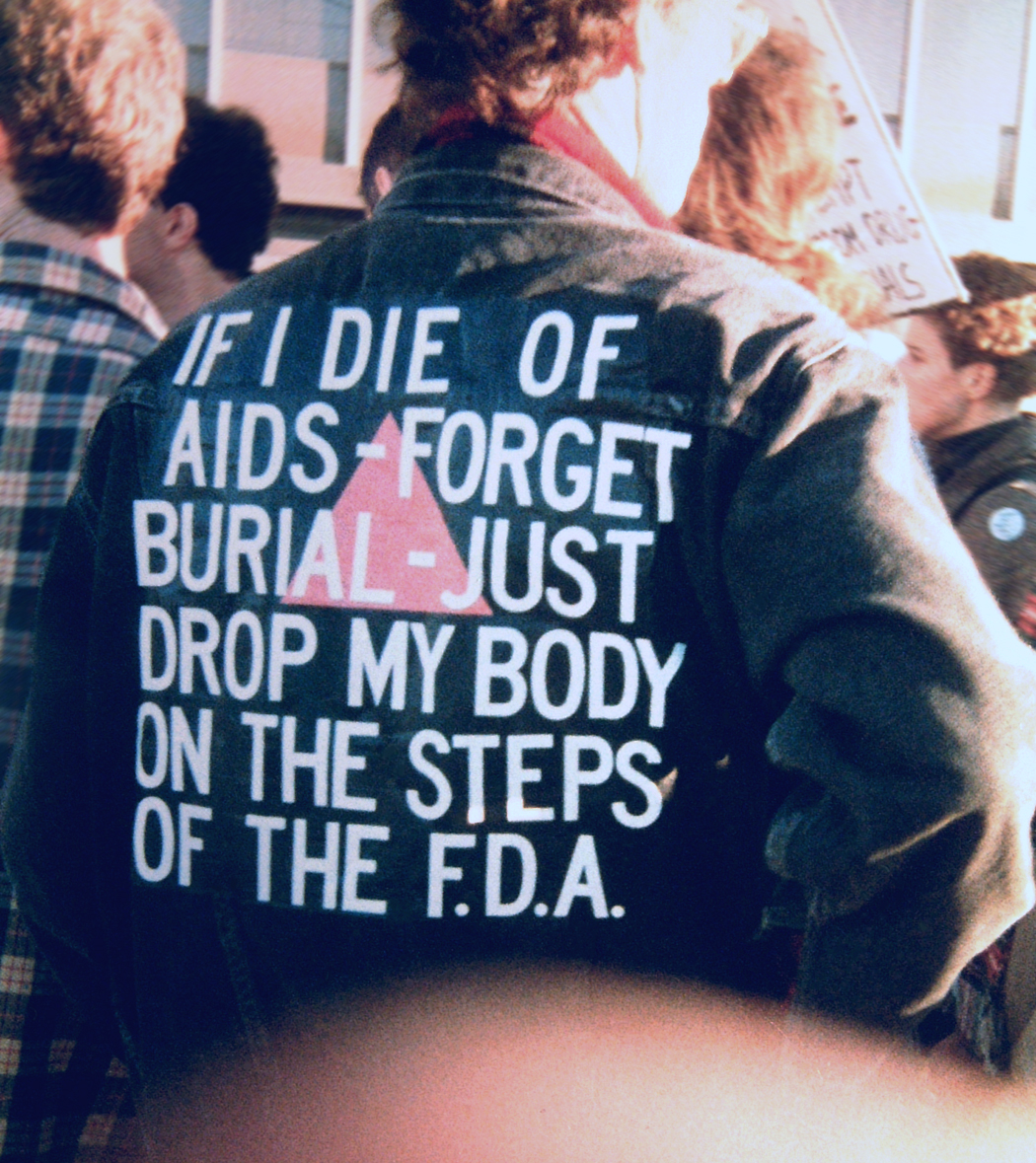

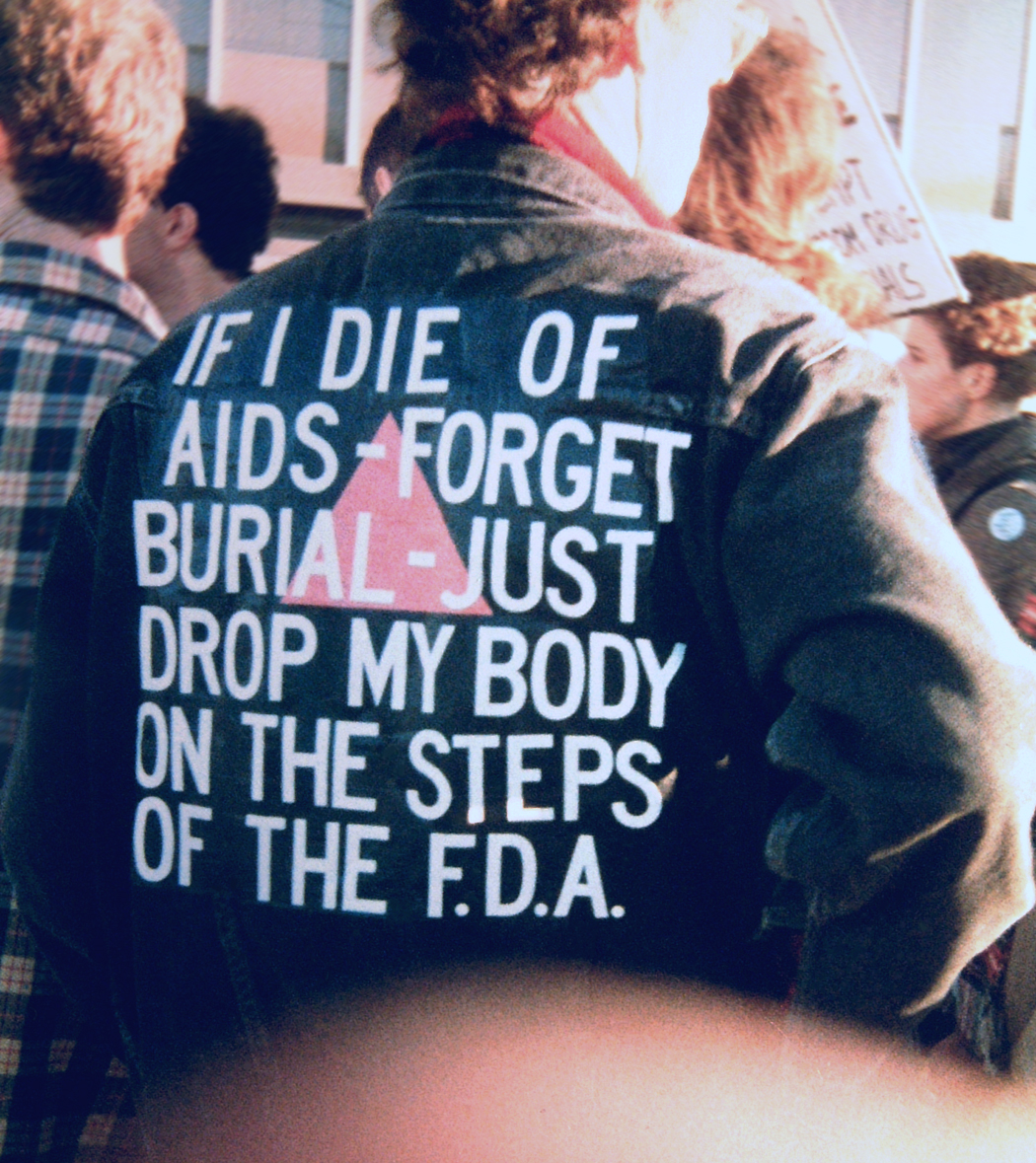

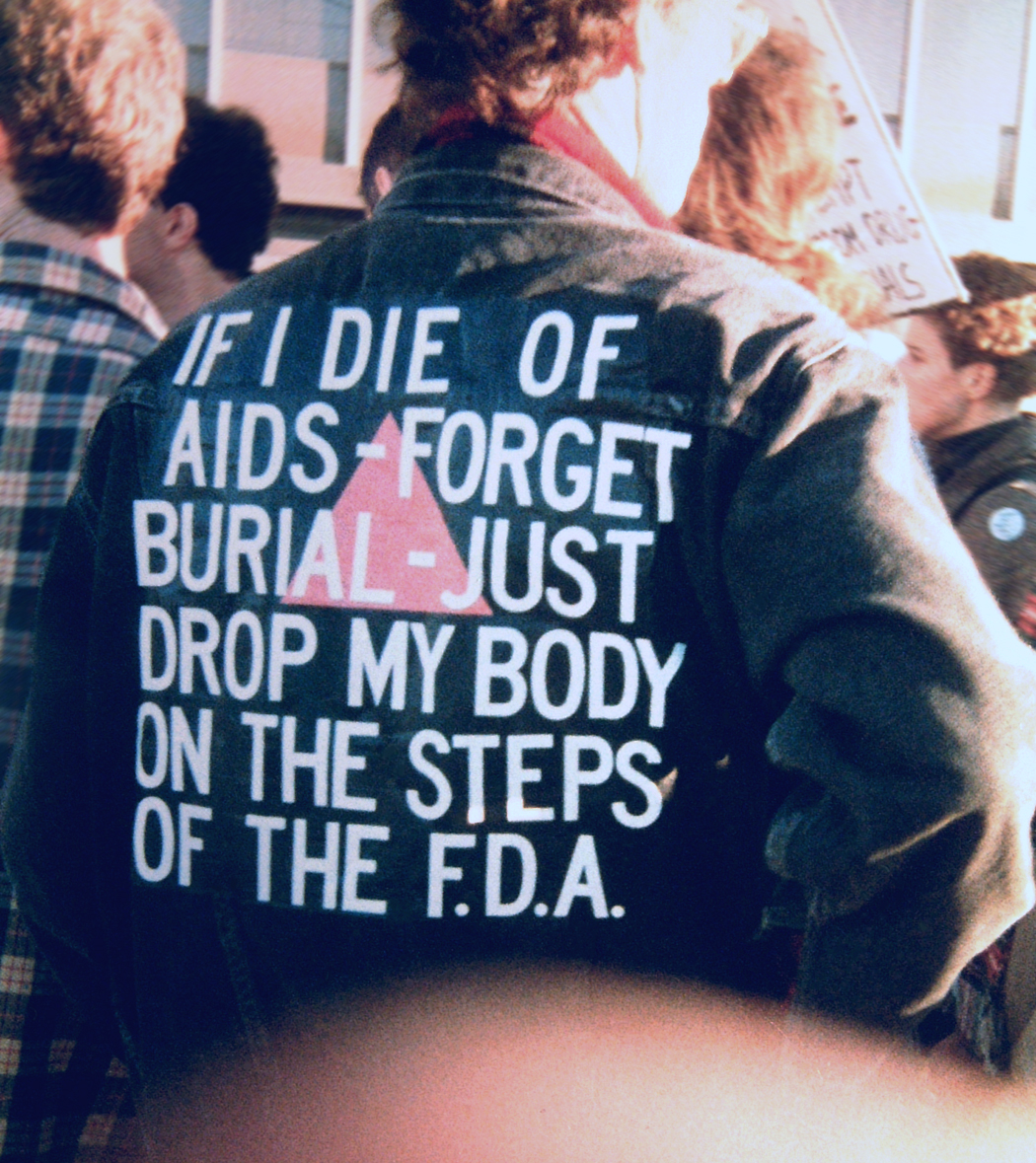

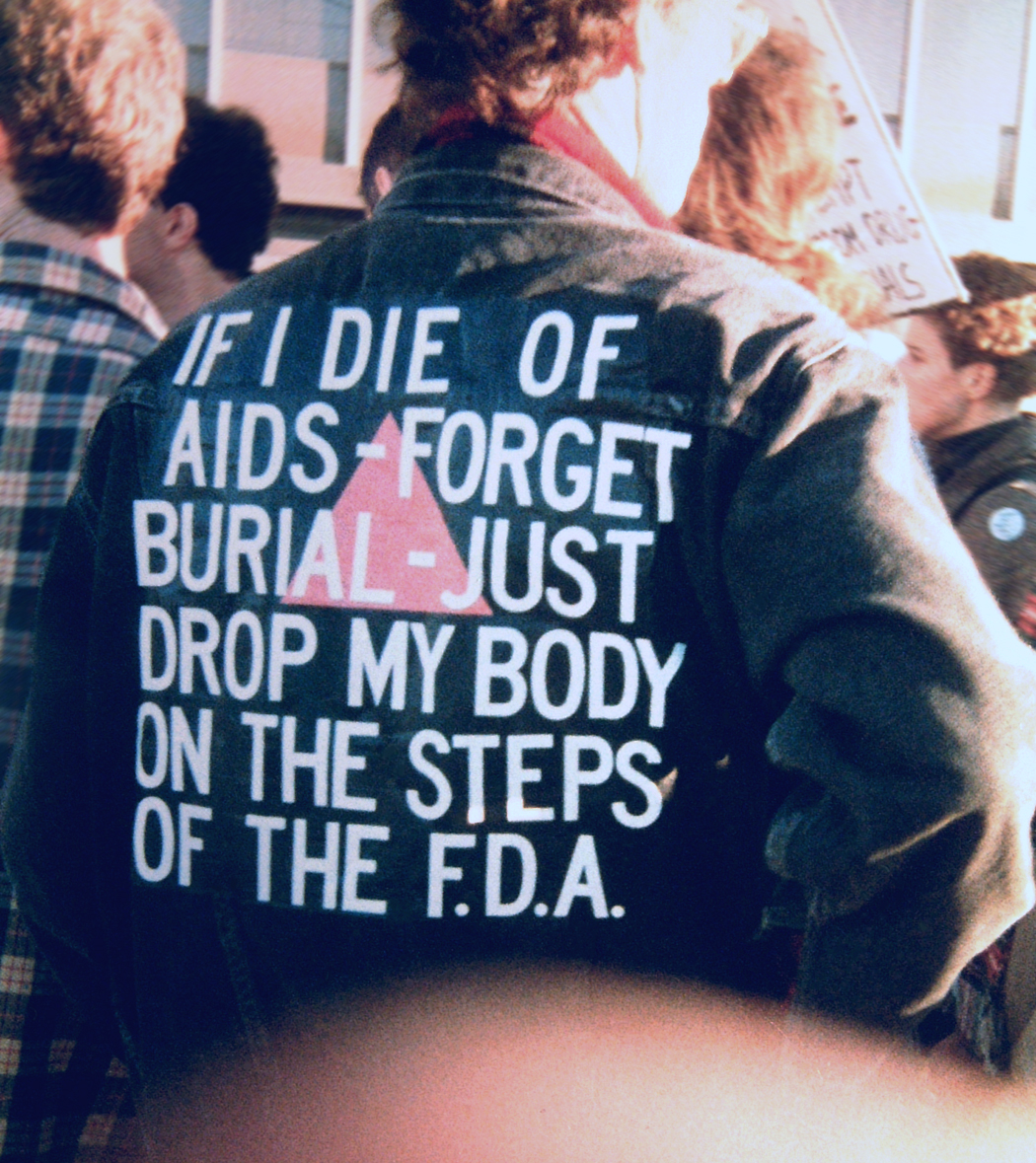

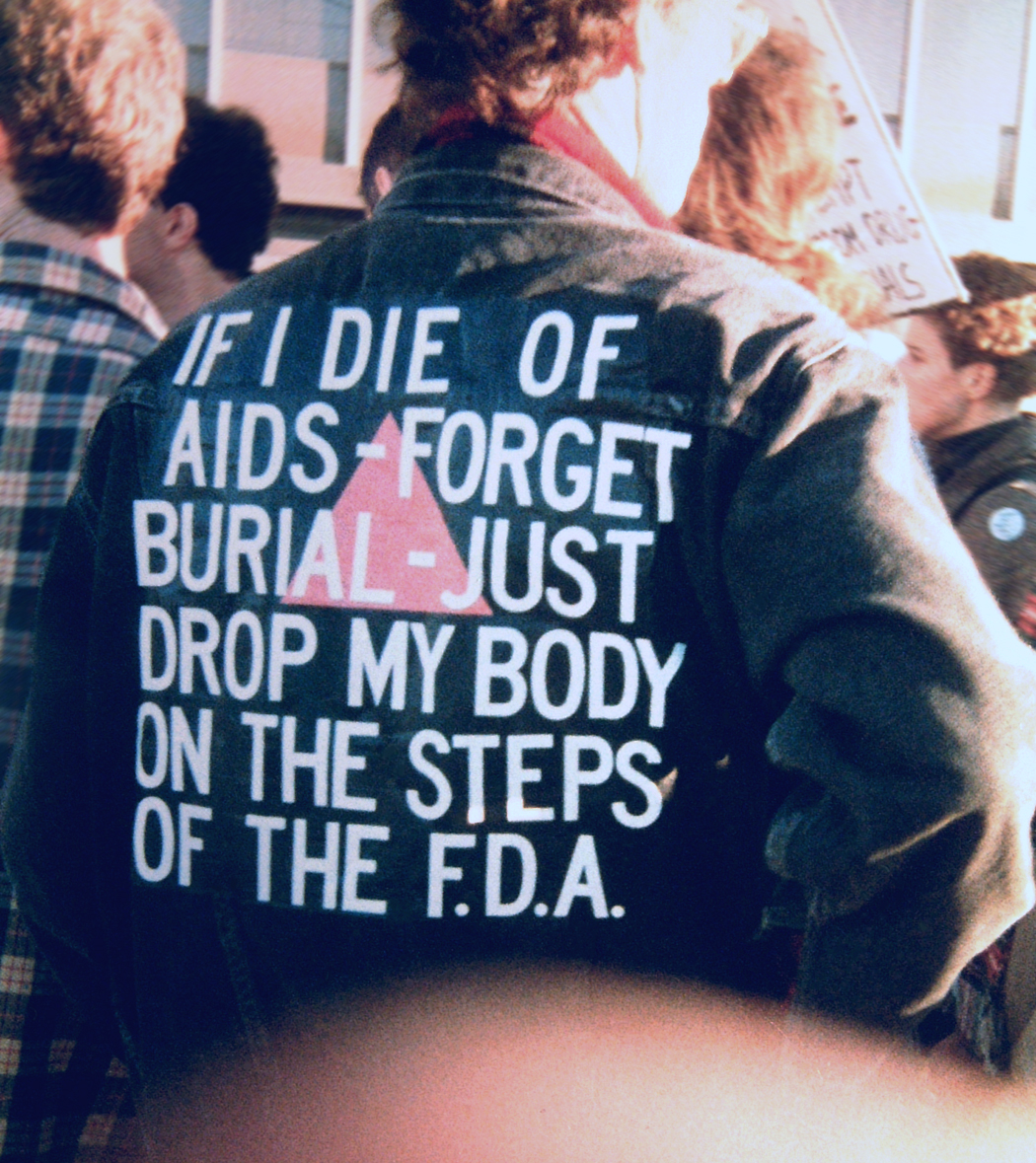

“IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.,” jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs.

And I think about David Wojnarowicz’s jacket here, worn by him at an ACT UP demonstration 32 years ago, during a different pandemic. It’s certainly an individual expression, but I see it first as an act of protest, speaking within and on behalf of the collective, and then as a gesture of publishing, manifesting an urgent message in public space, using the very body that is the subject of that message, the body that will die of the disease, as the platform for its dissemination. This jacket is so many things. It’s art, it’s graphic design, it’s a shared plea, it’s a protest at a very particular moment. It’s an urgent artifact.

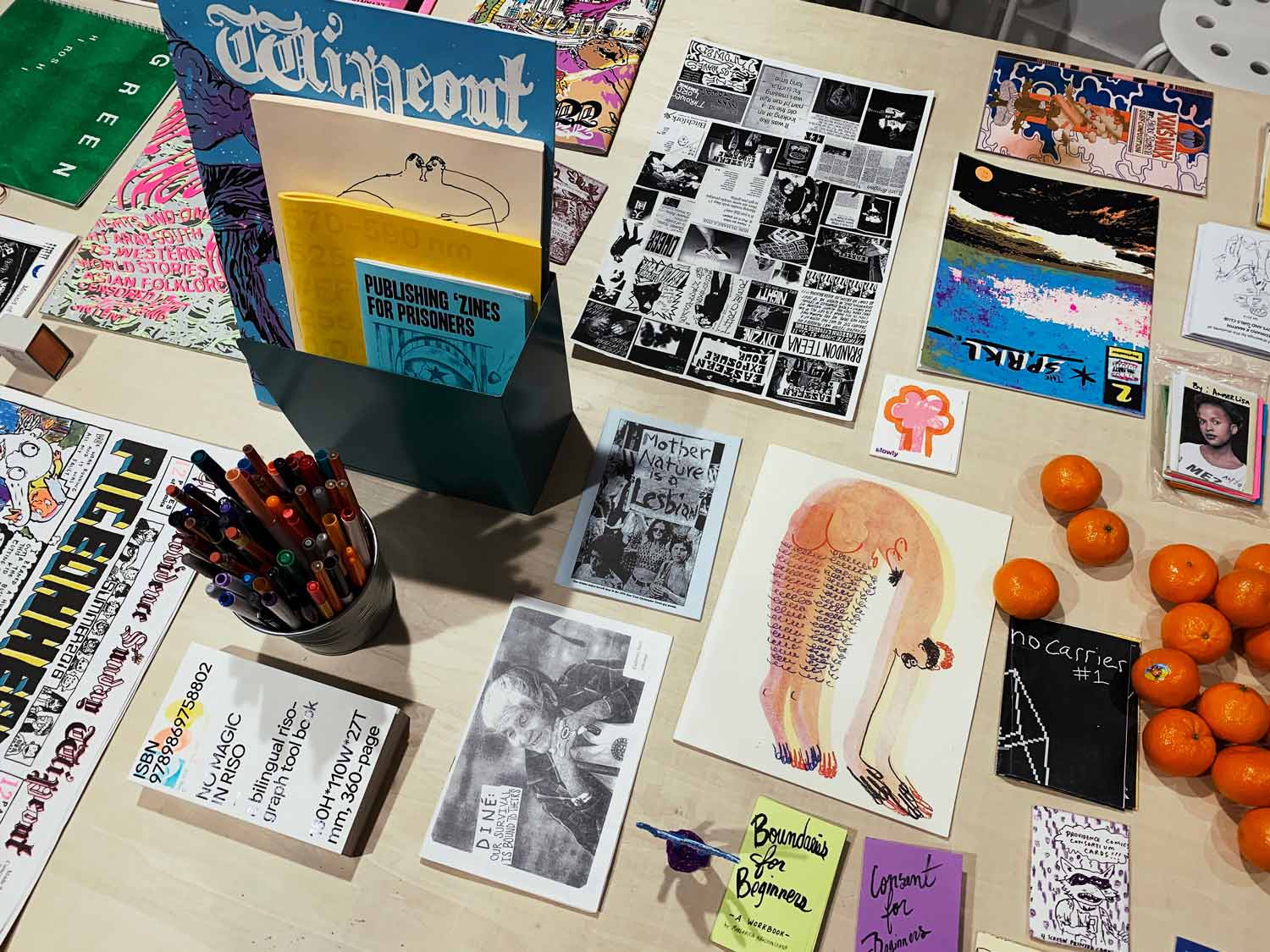

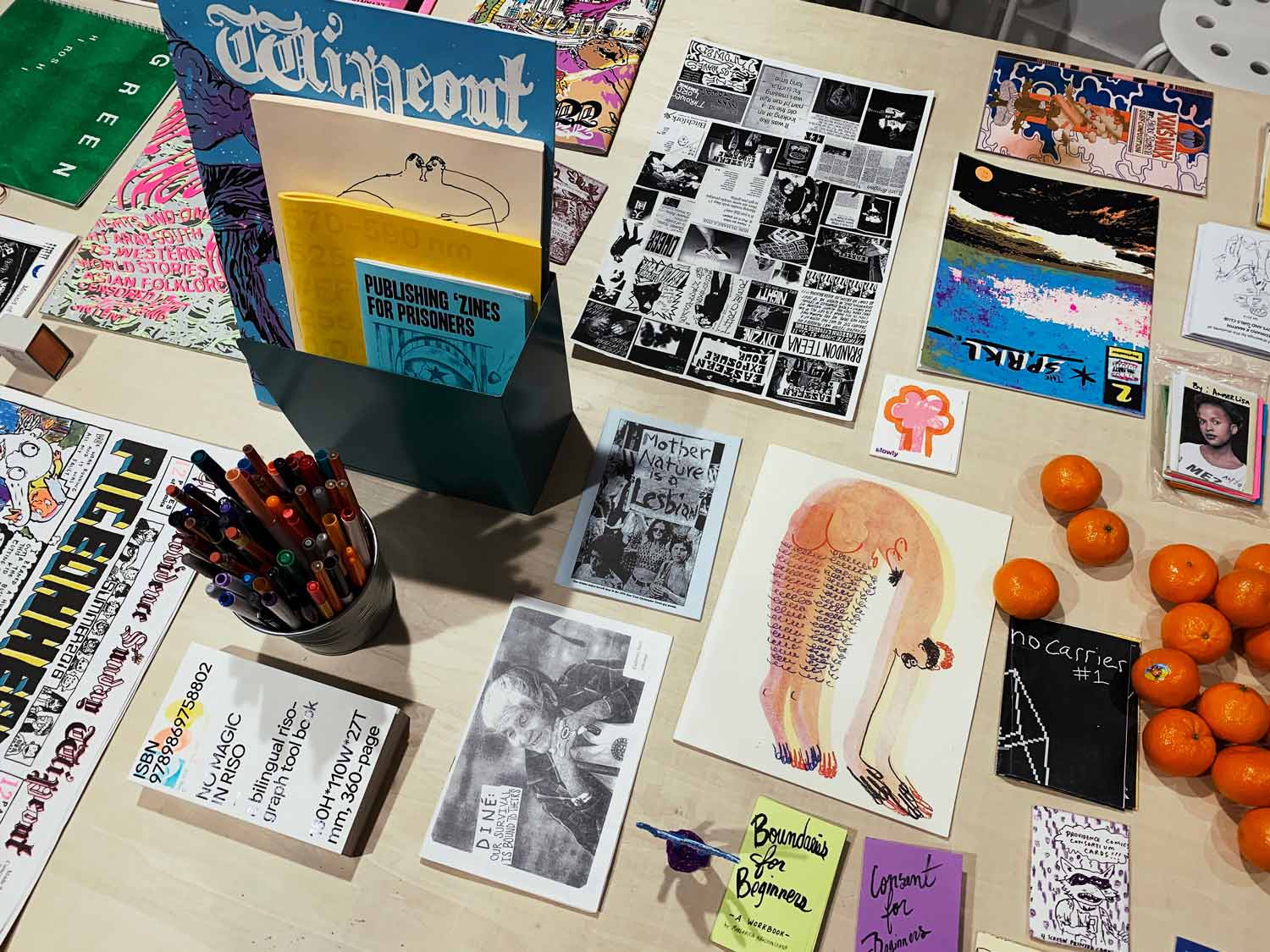

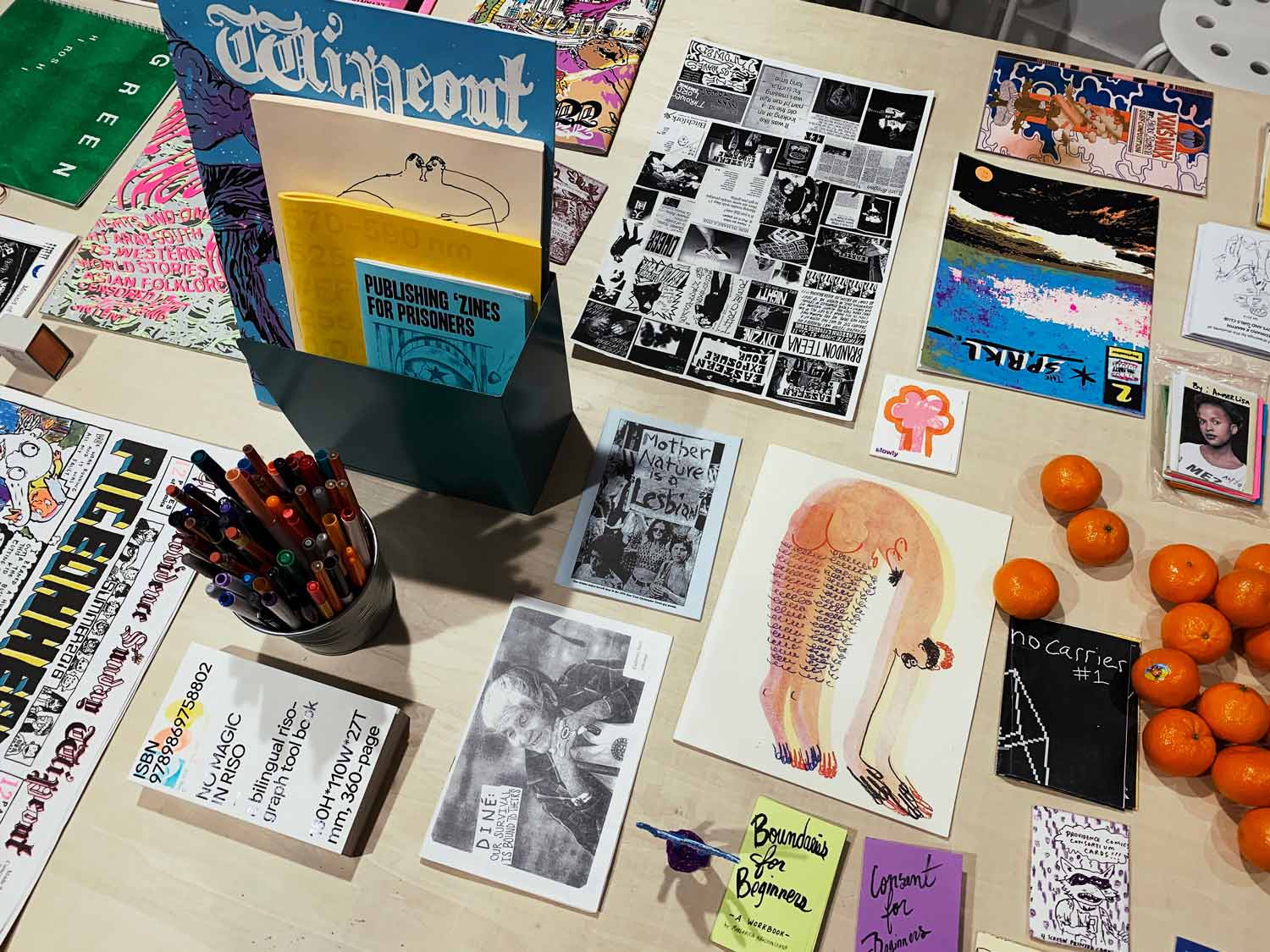

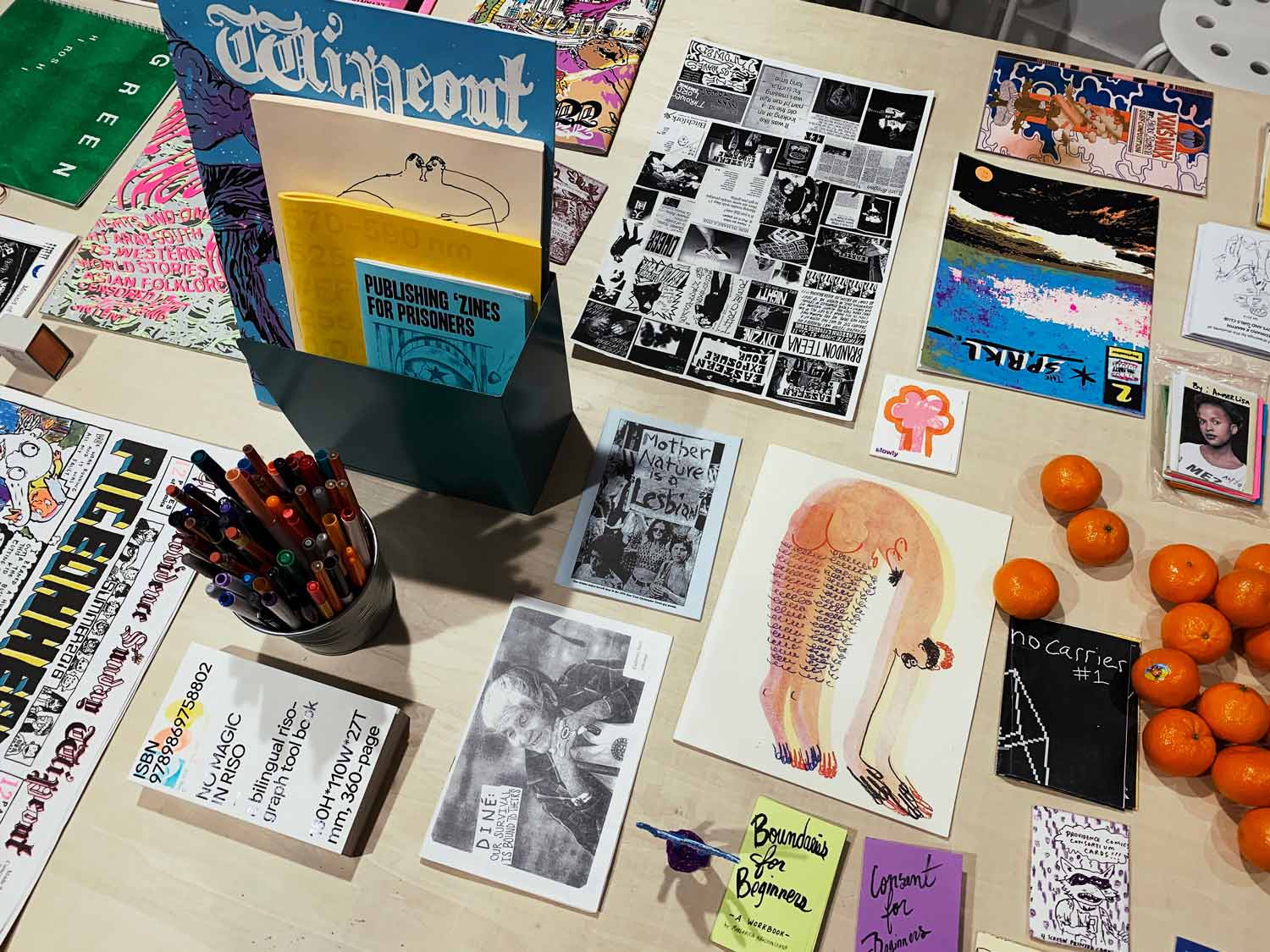

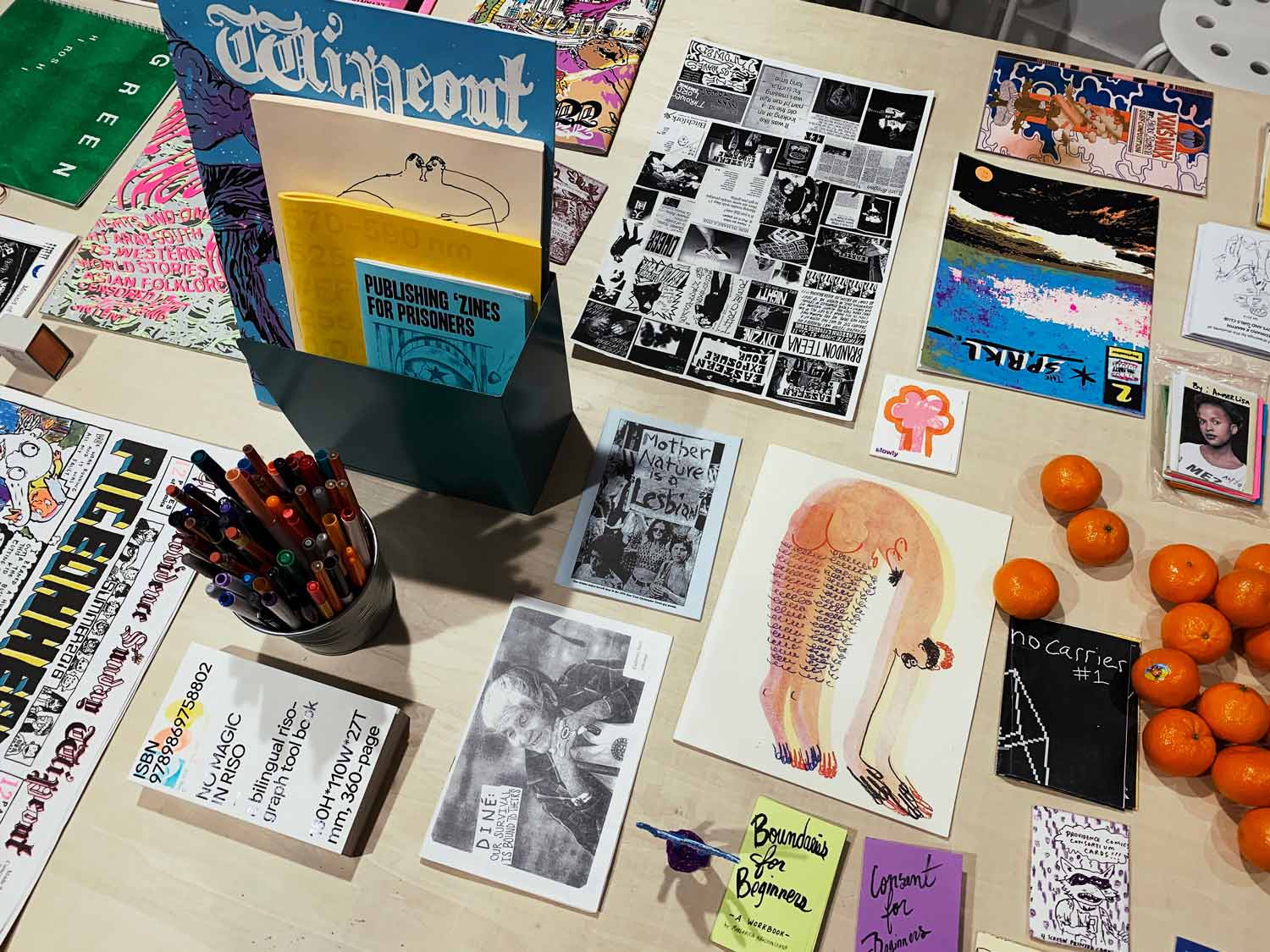

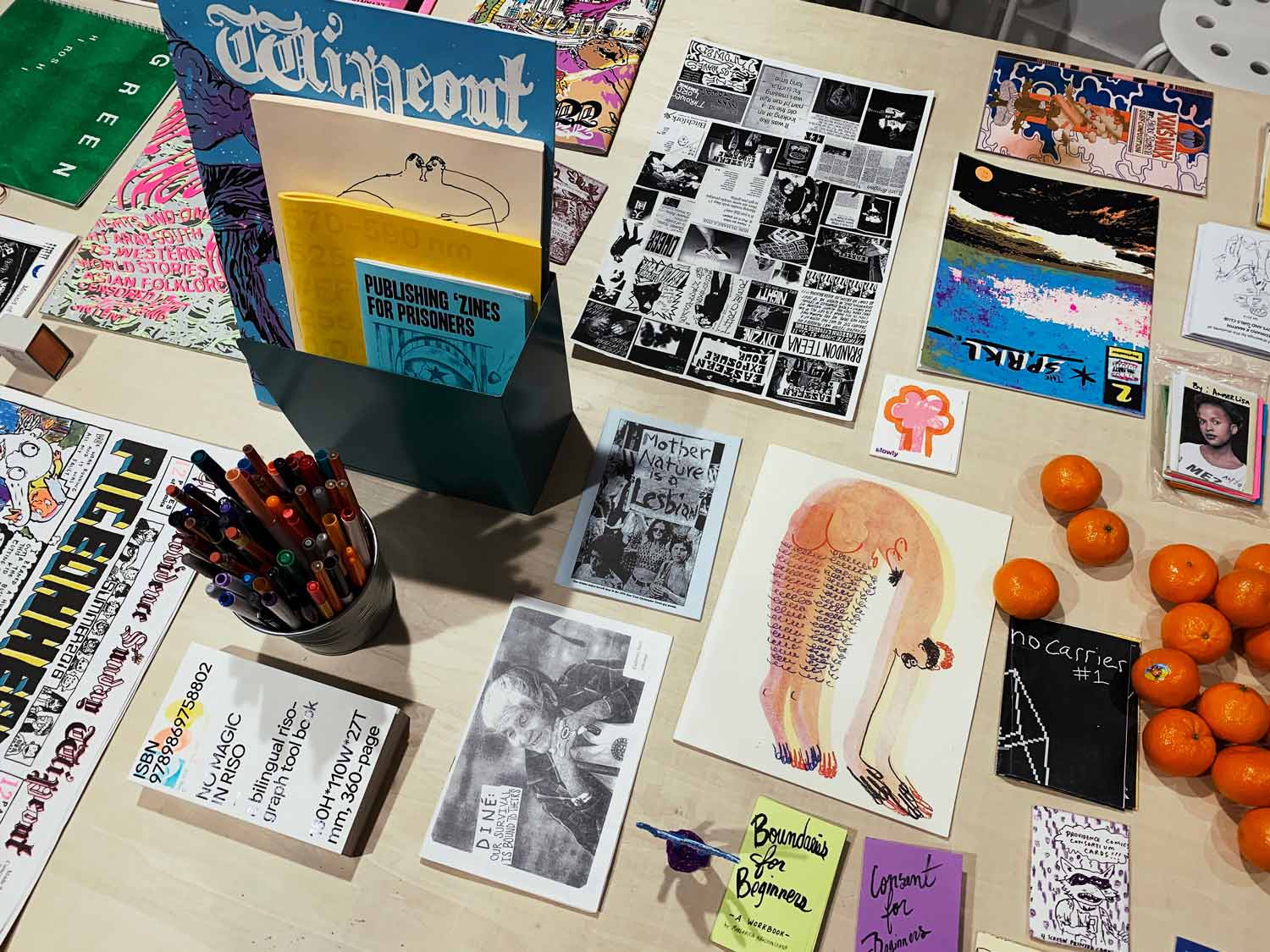

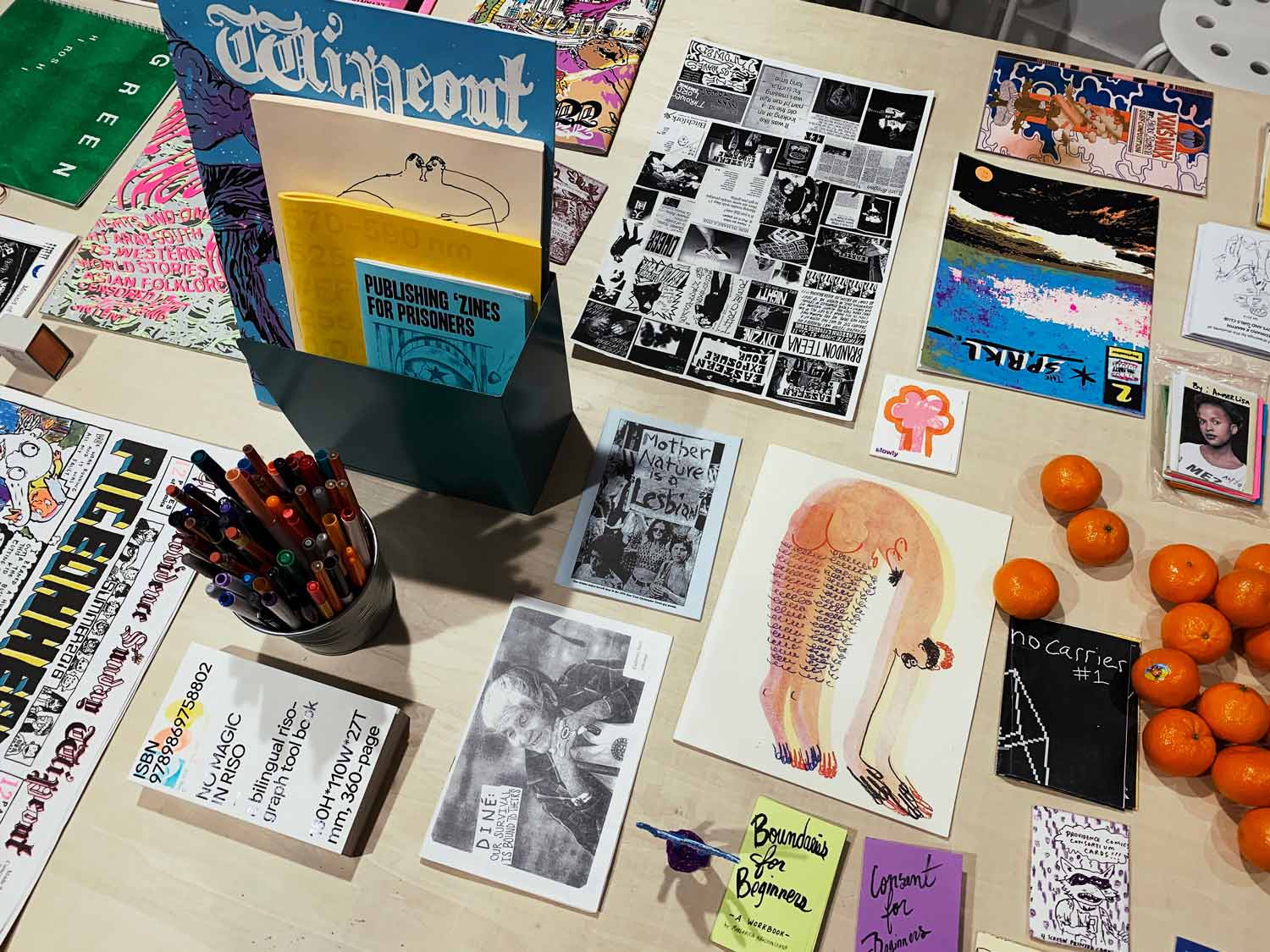

Asian American Feminist Collective zine

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts, the proof that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

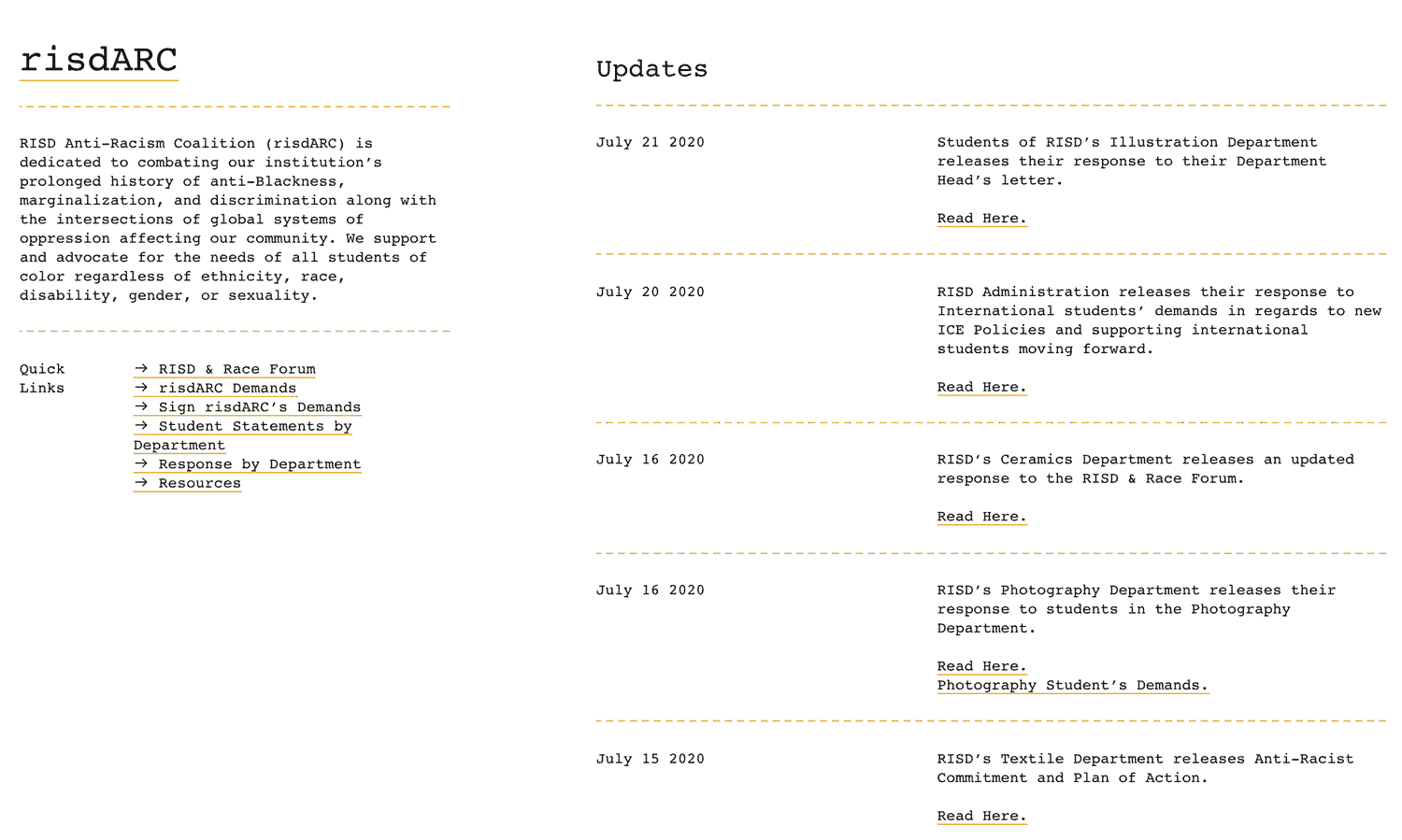

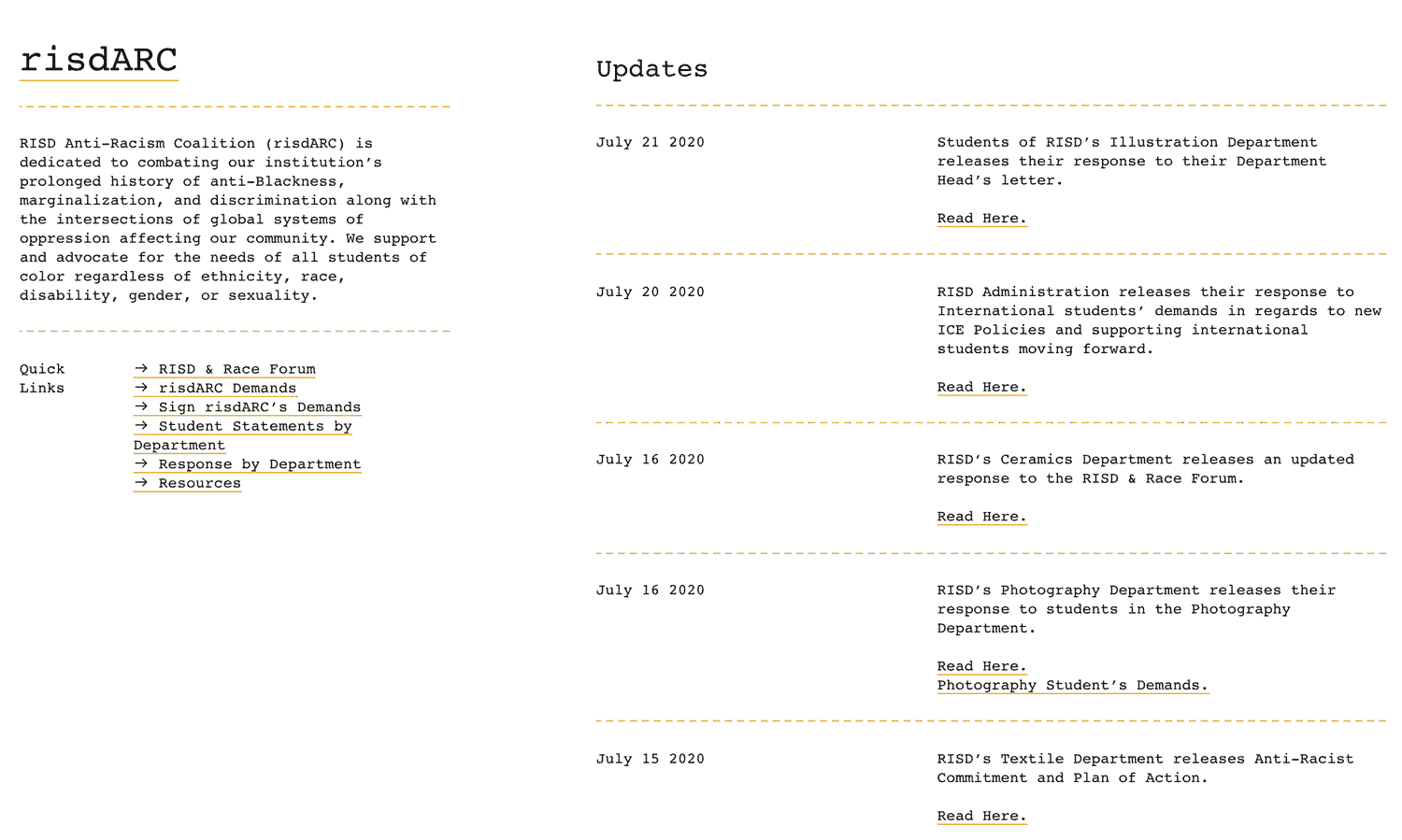

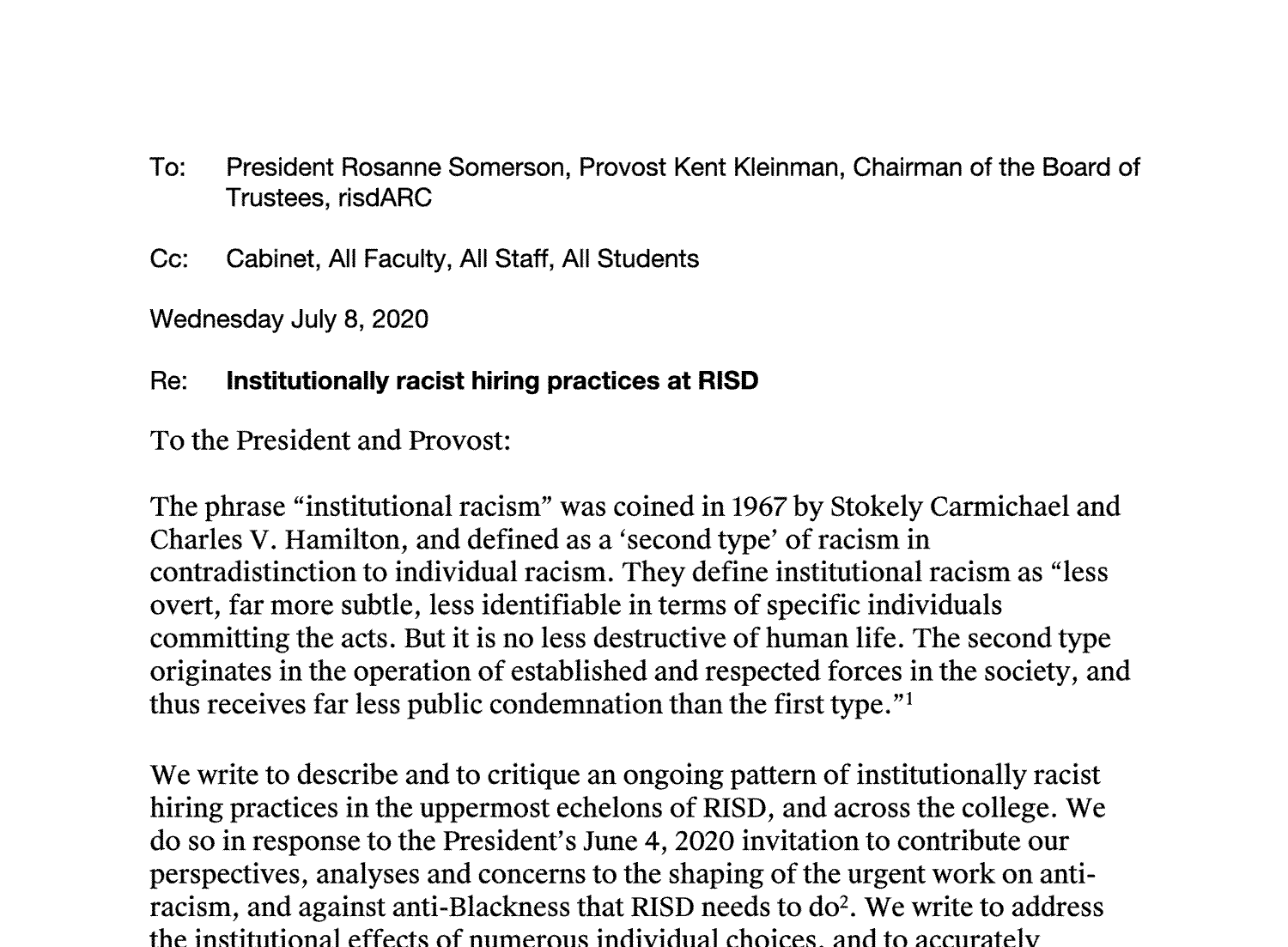

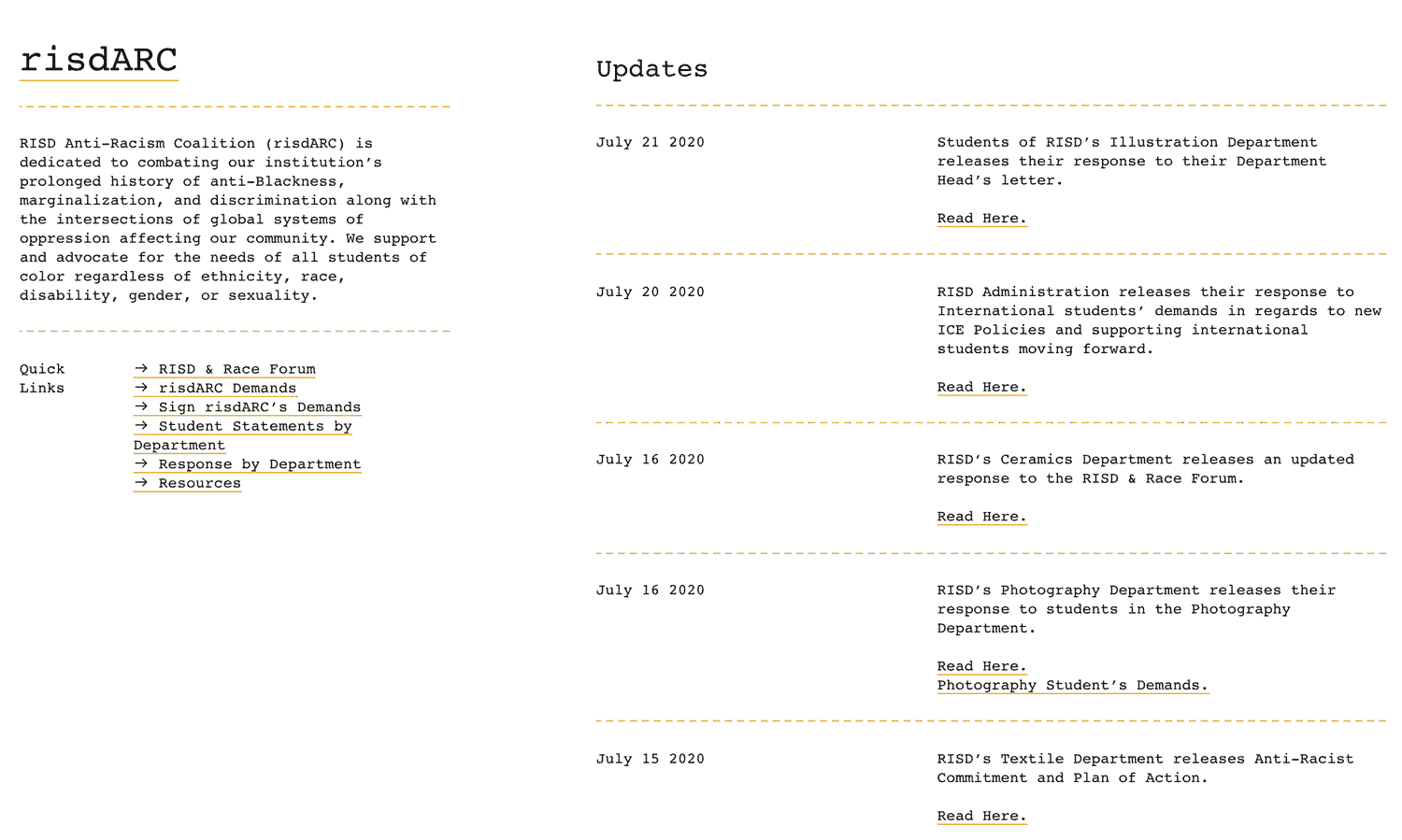

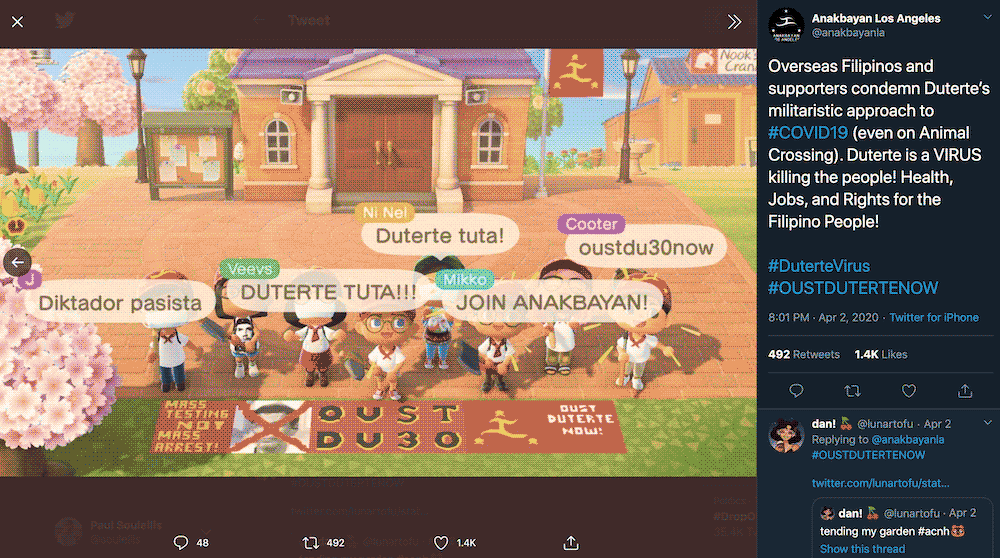

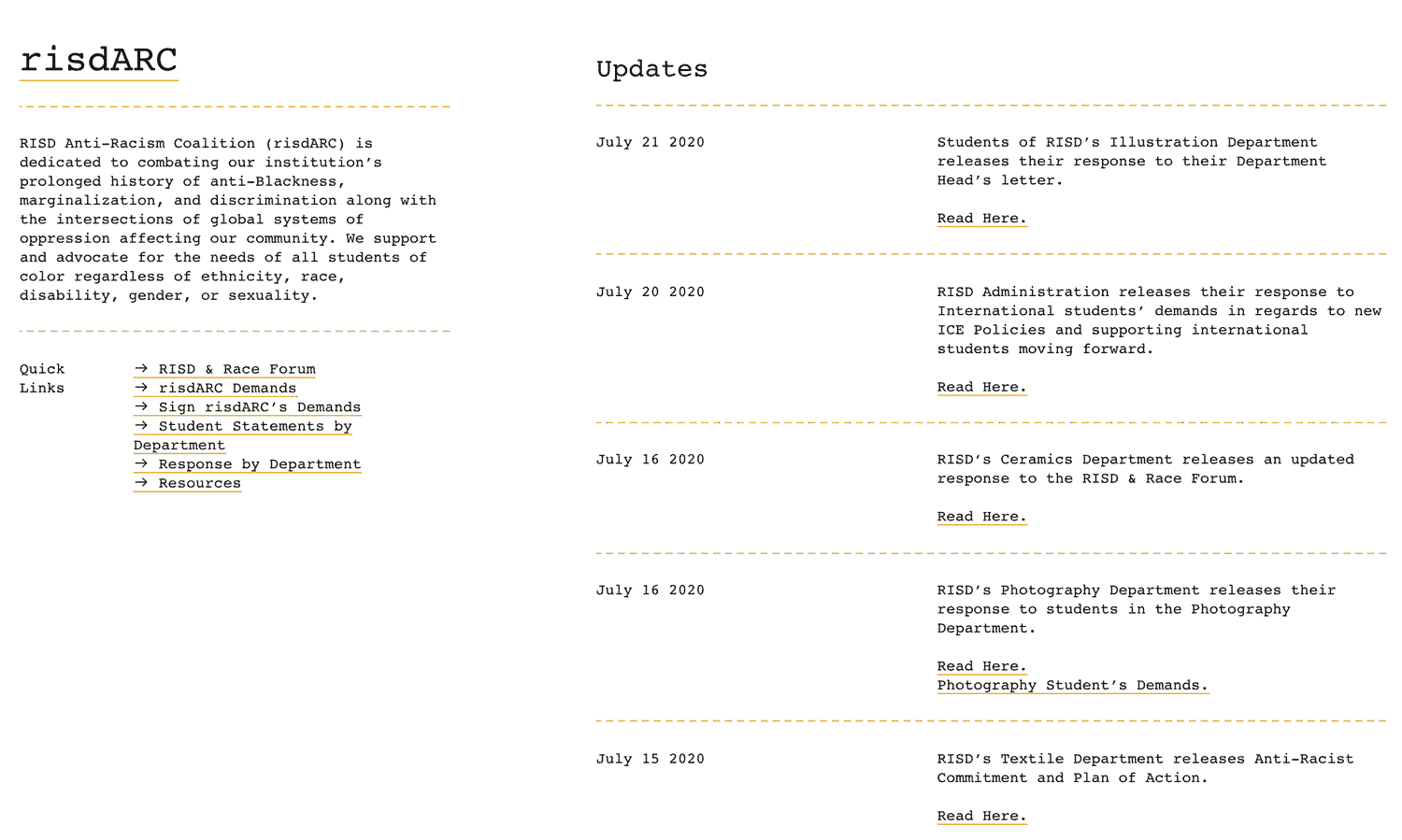

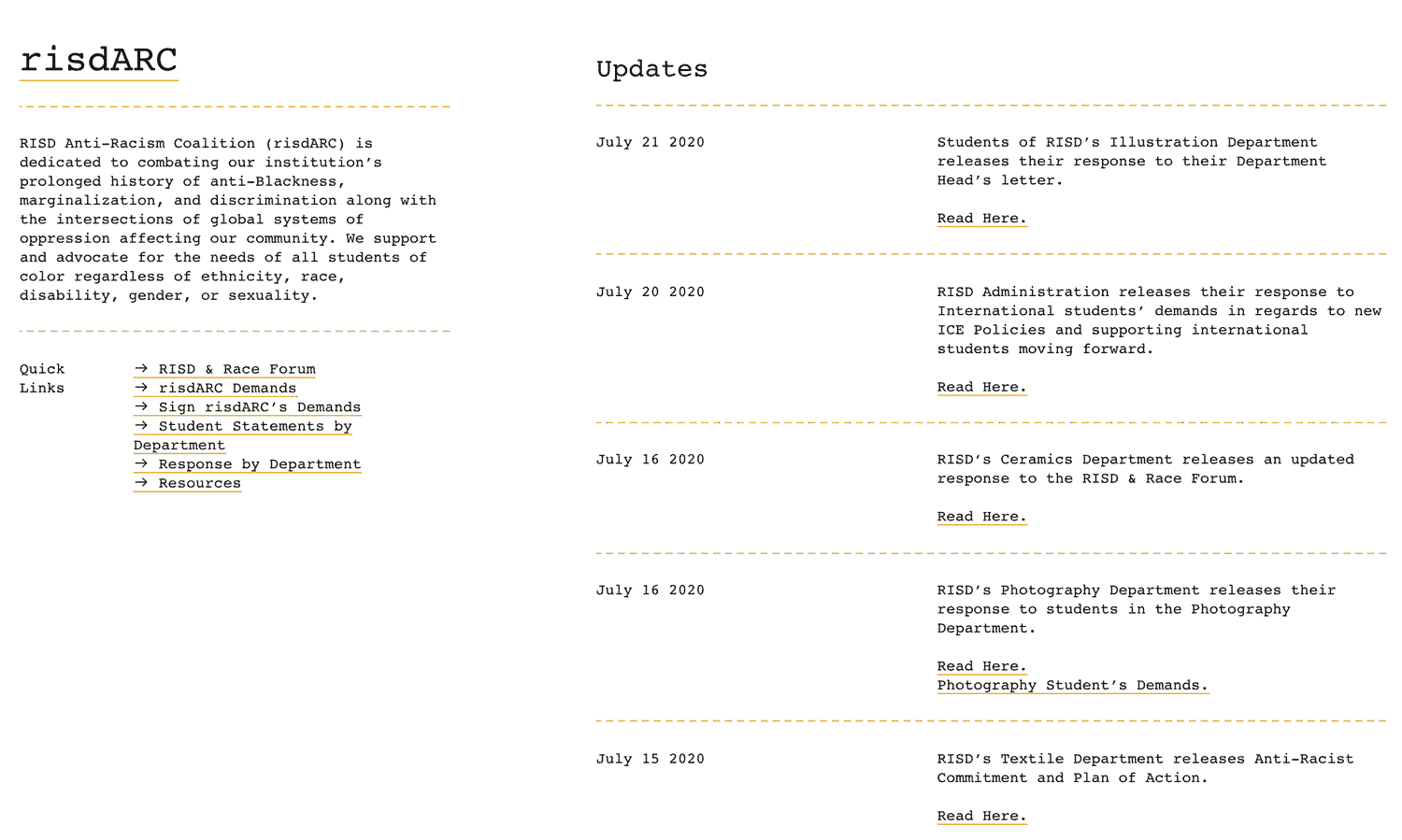

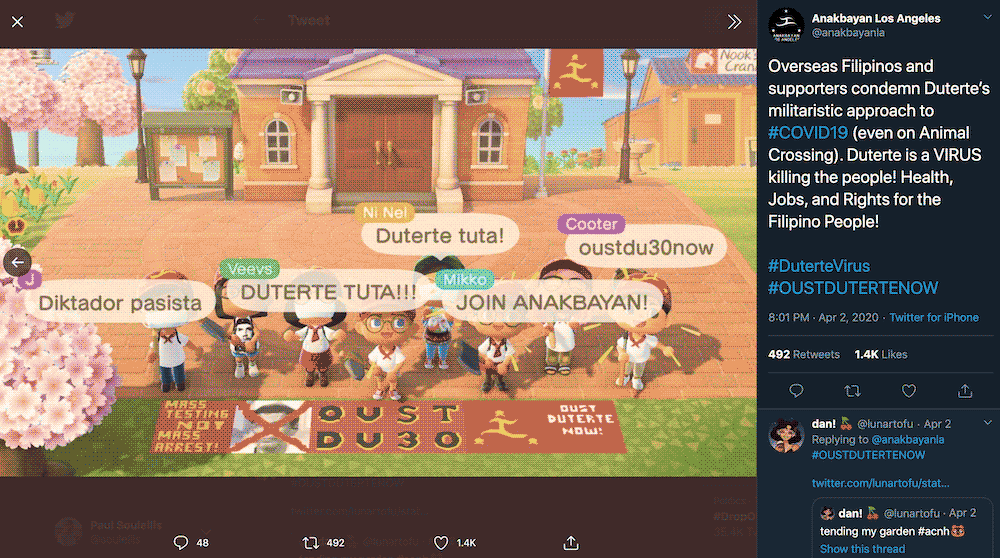

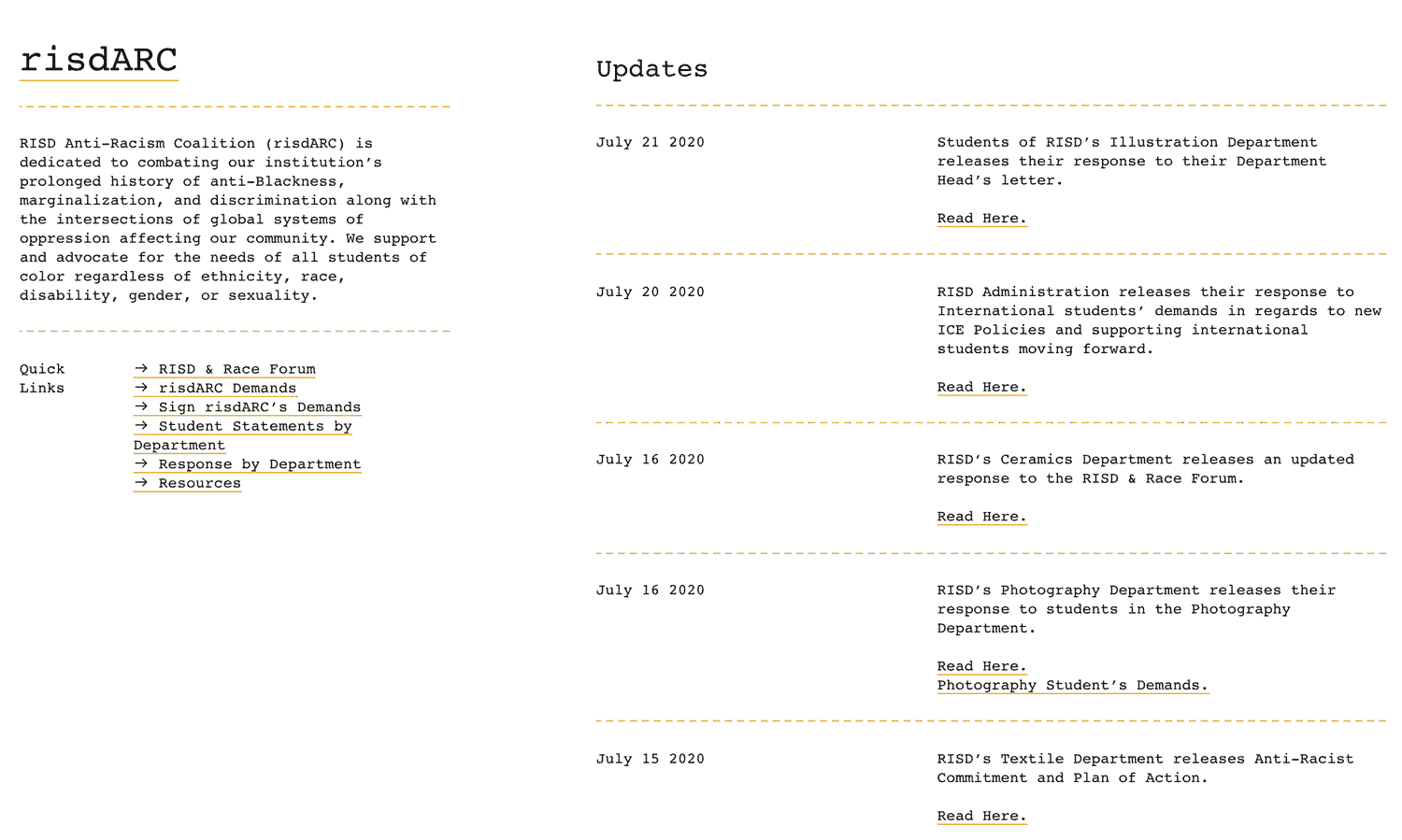

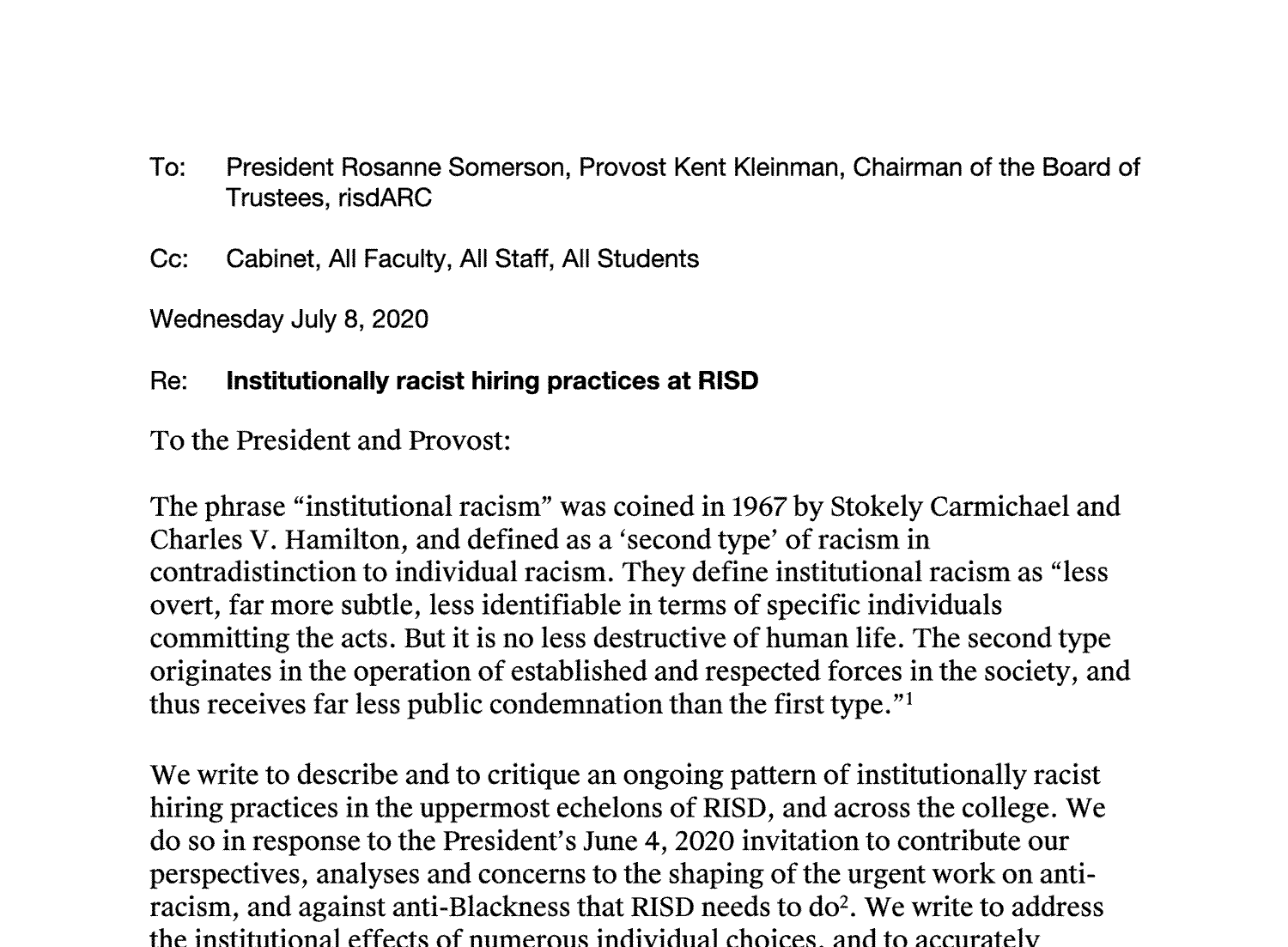

RISD Anti-Racism Coalition (risdARC), student-run initiative launched July 1, 2020

A letter from some junior BIPoC faculty regarding Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD, July 8, 2020

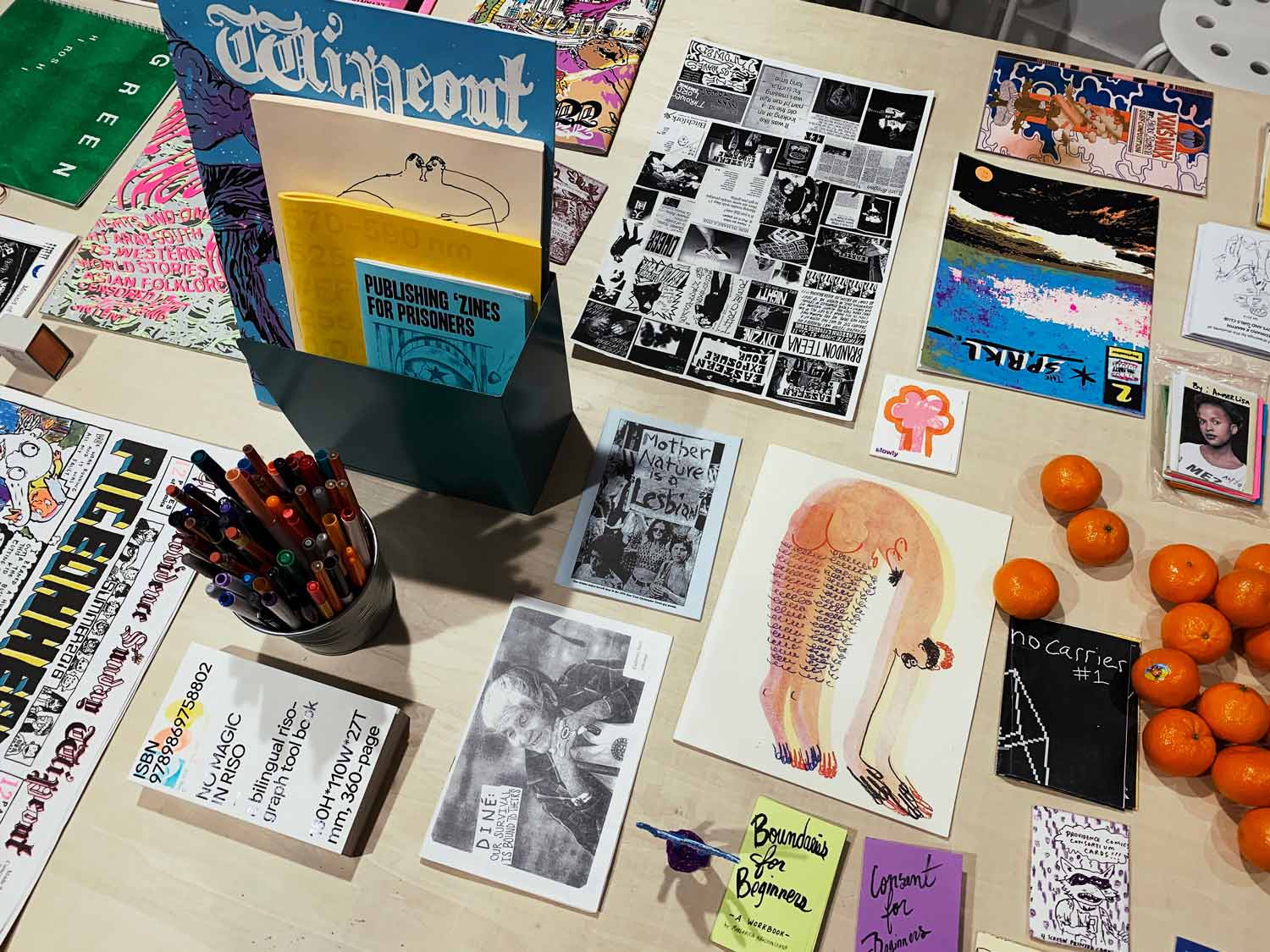

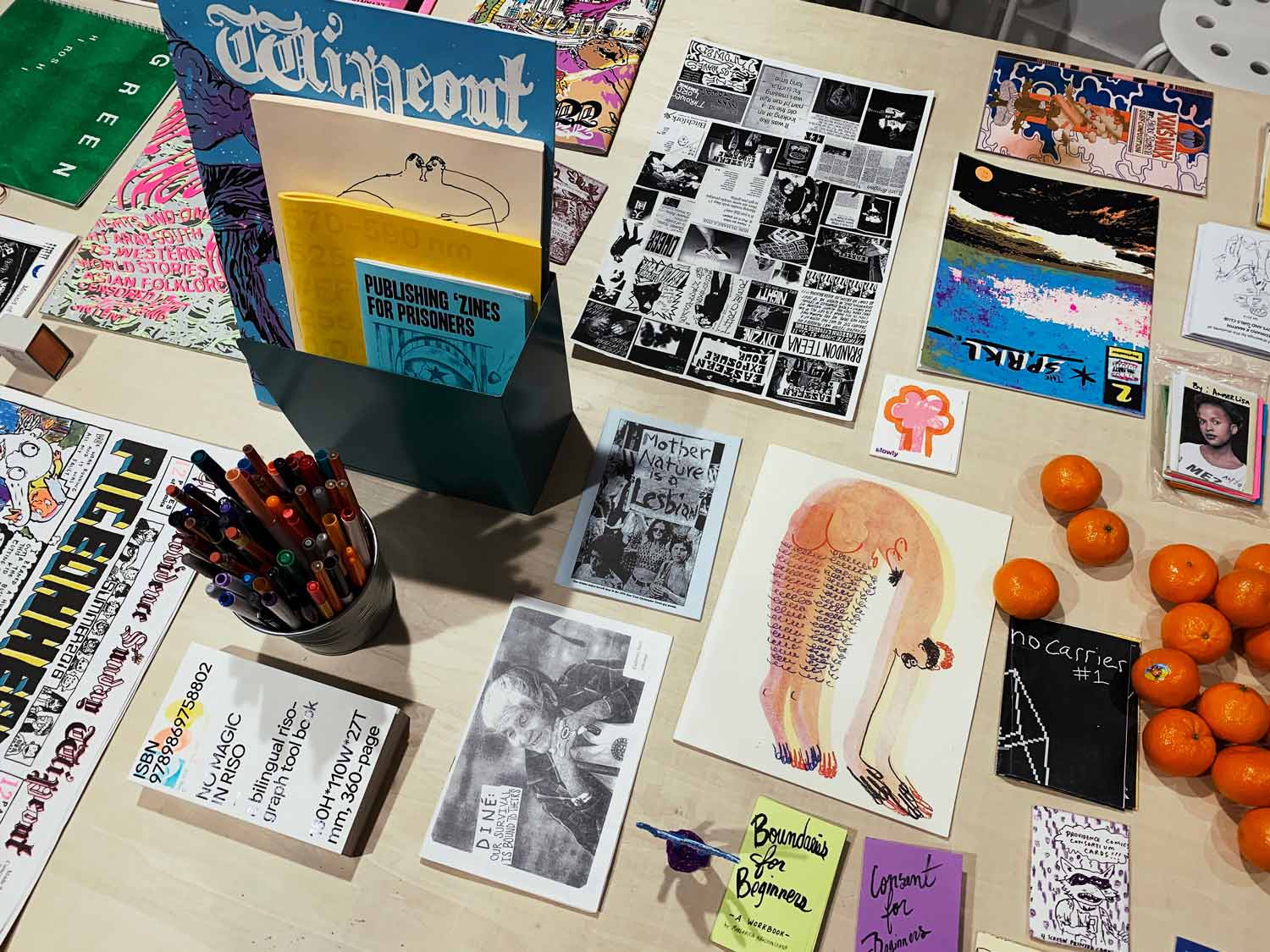

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, collaborative mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

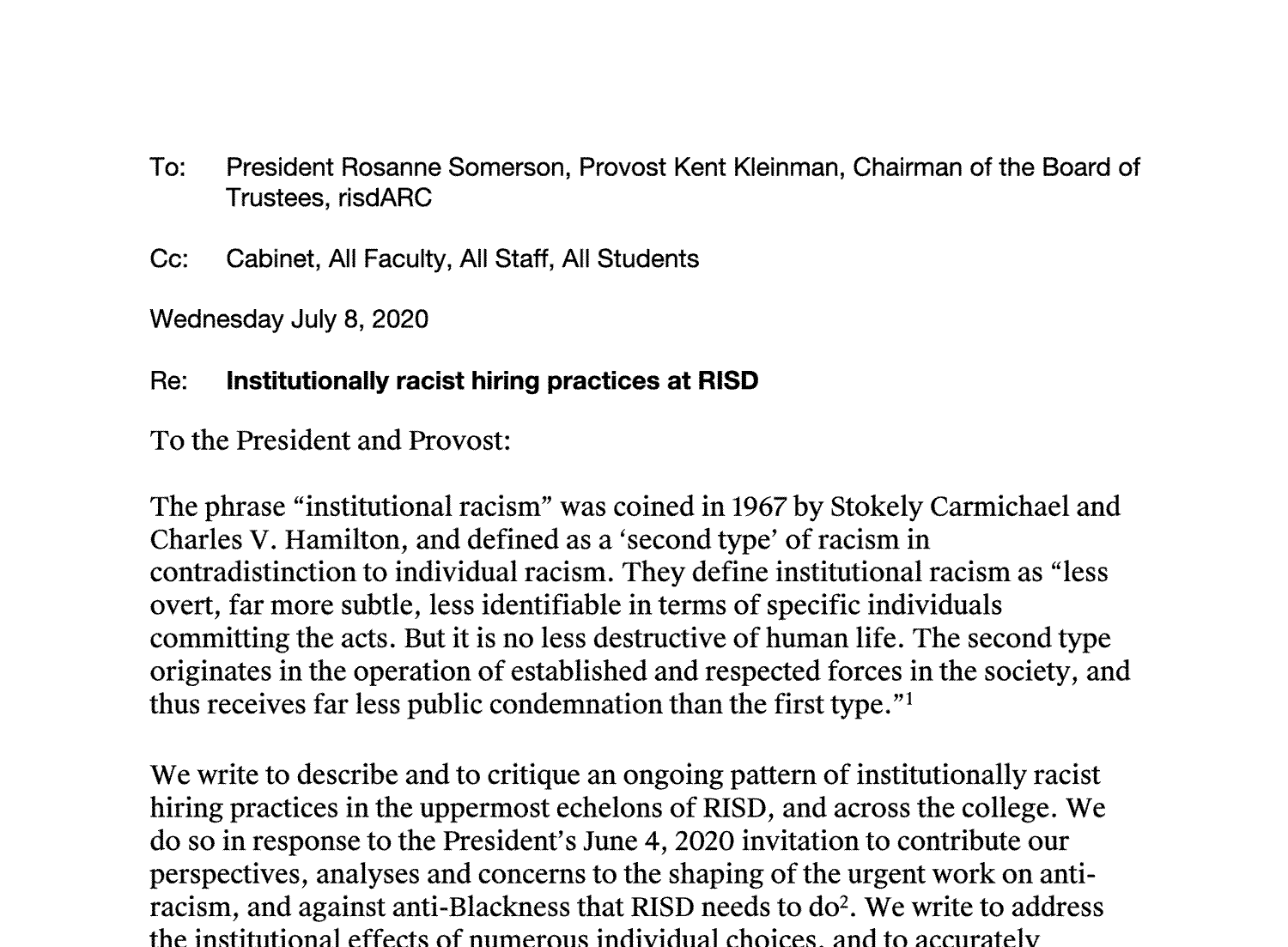

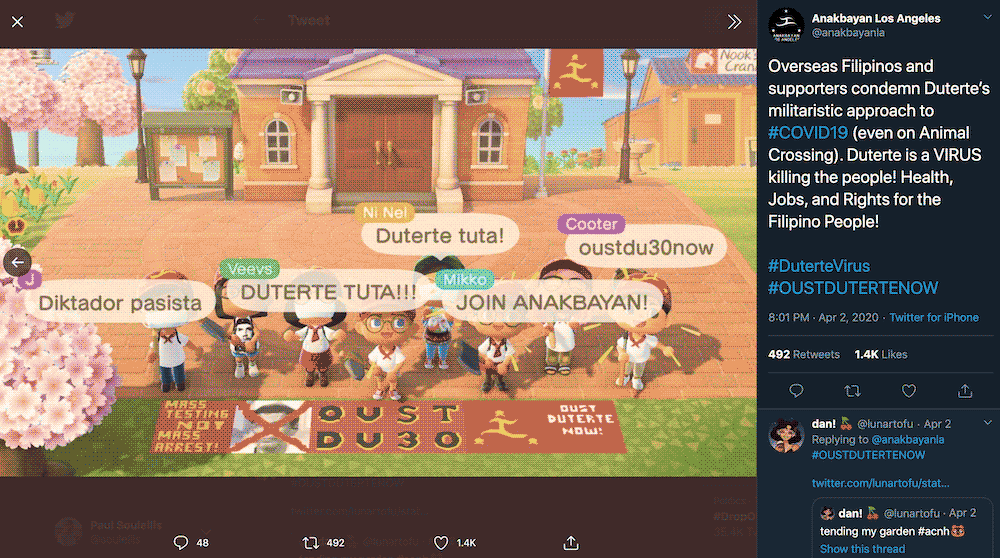

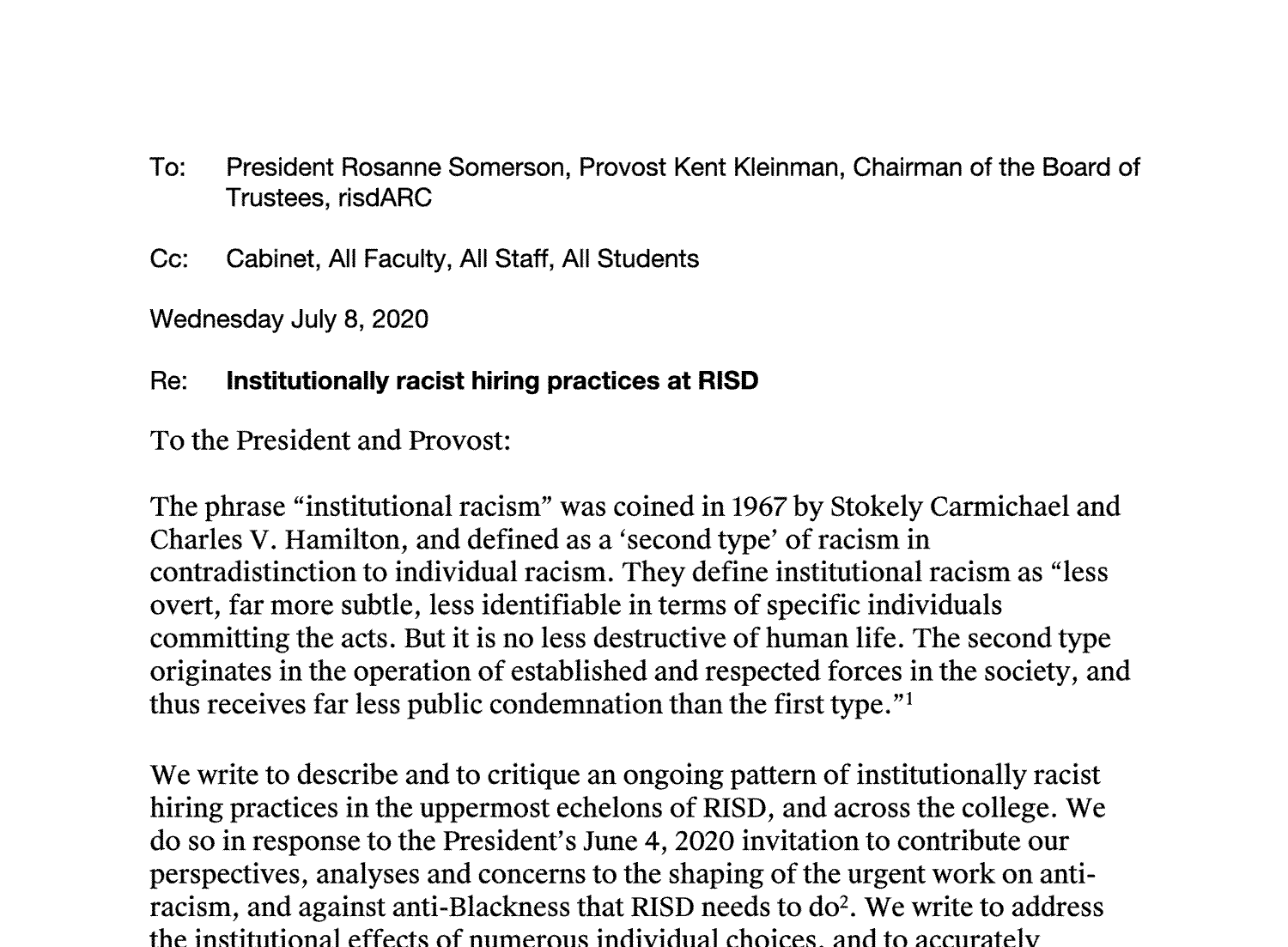

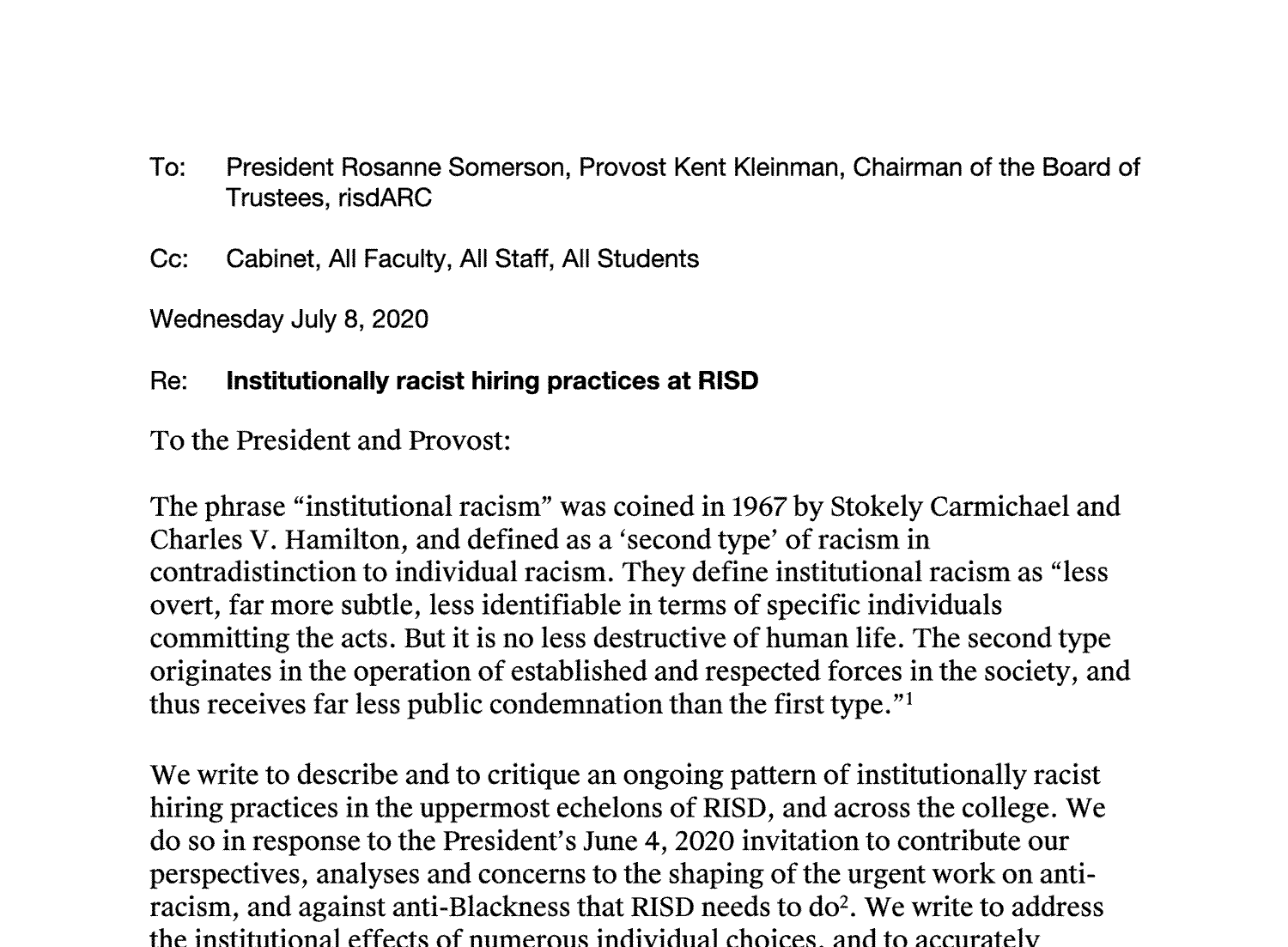

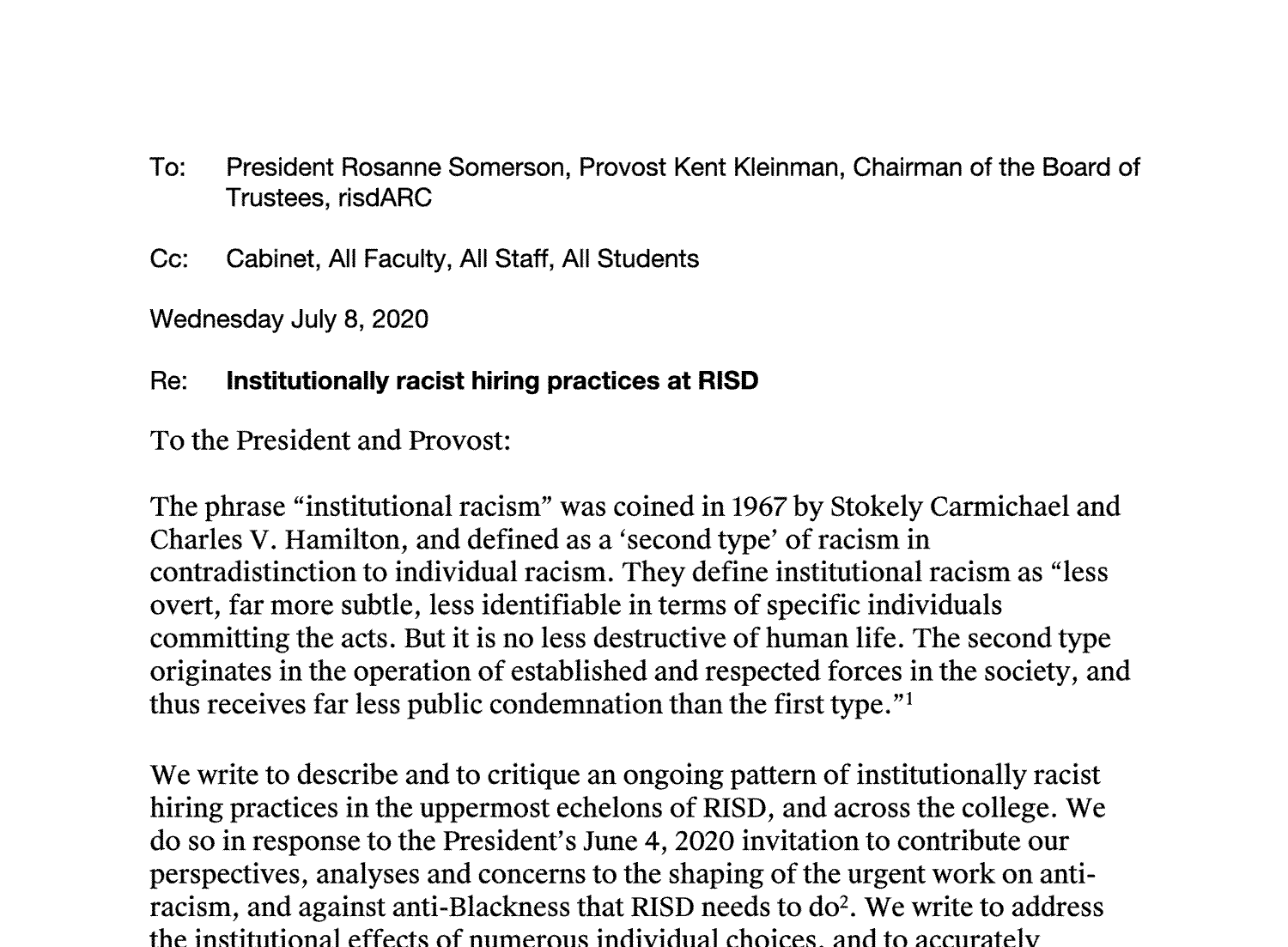

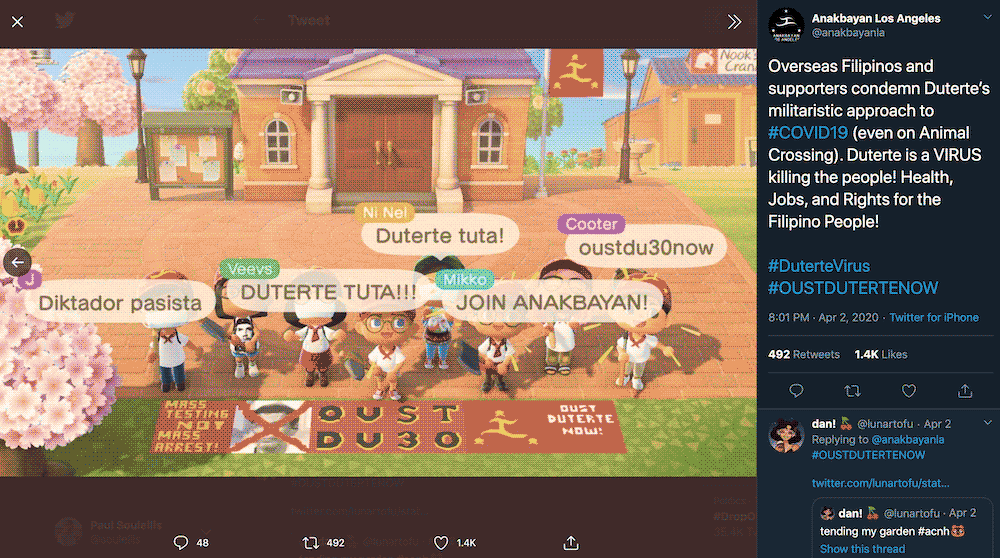

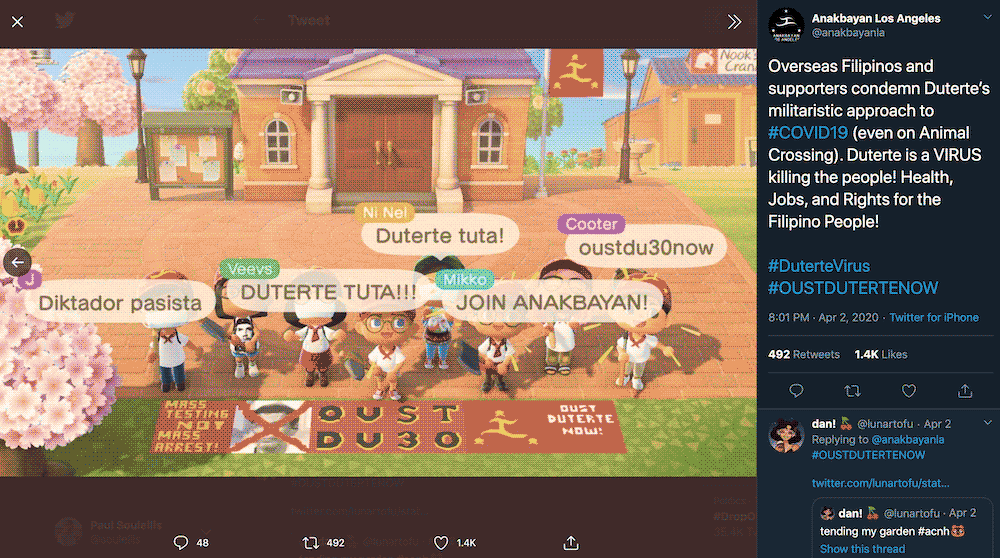

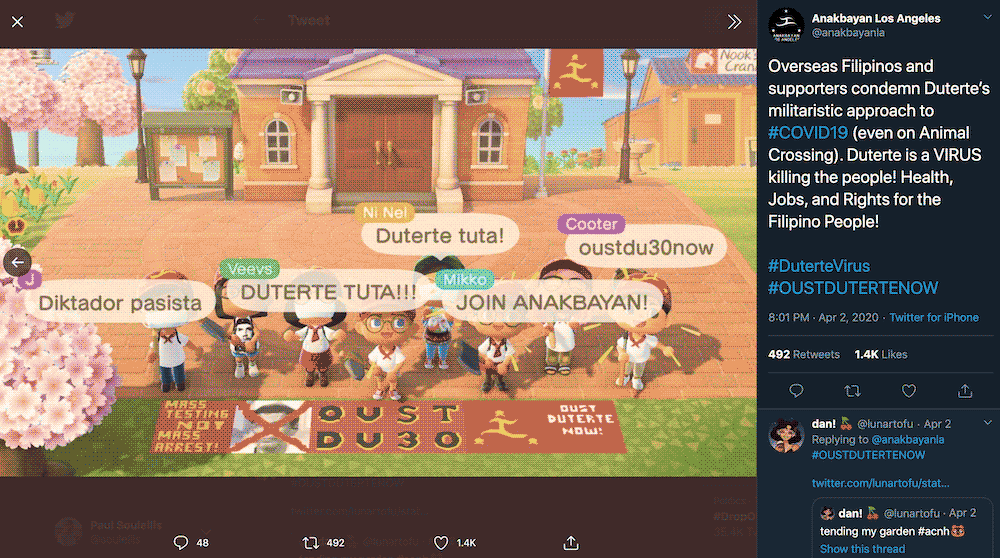

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

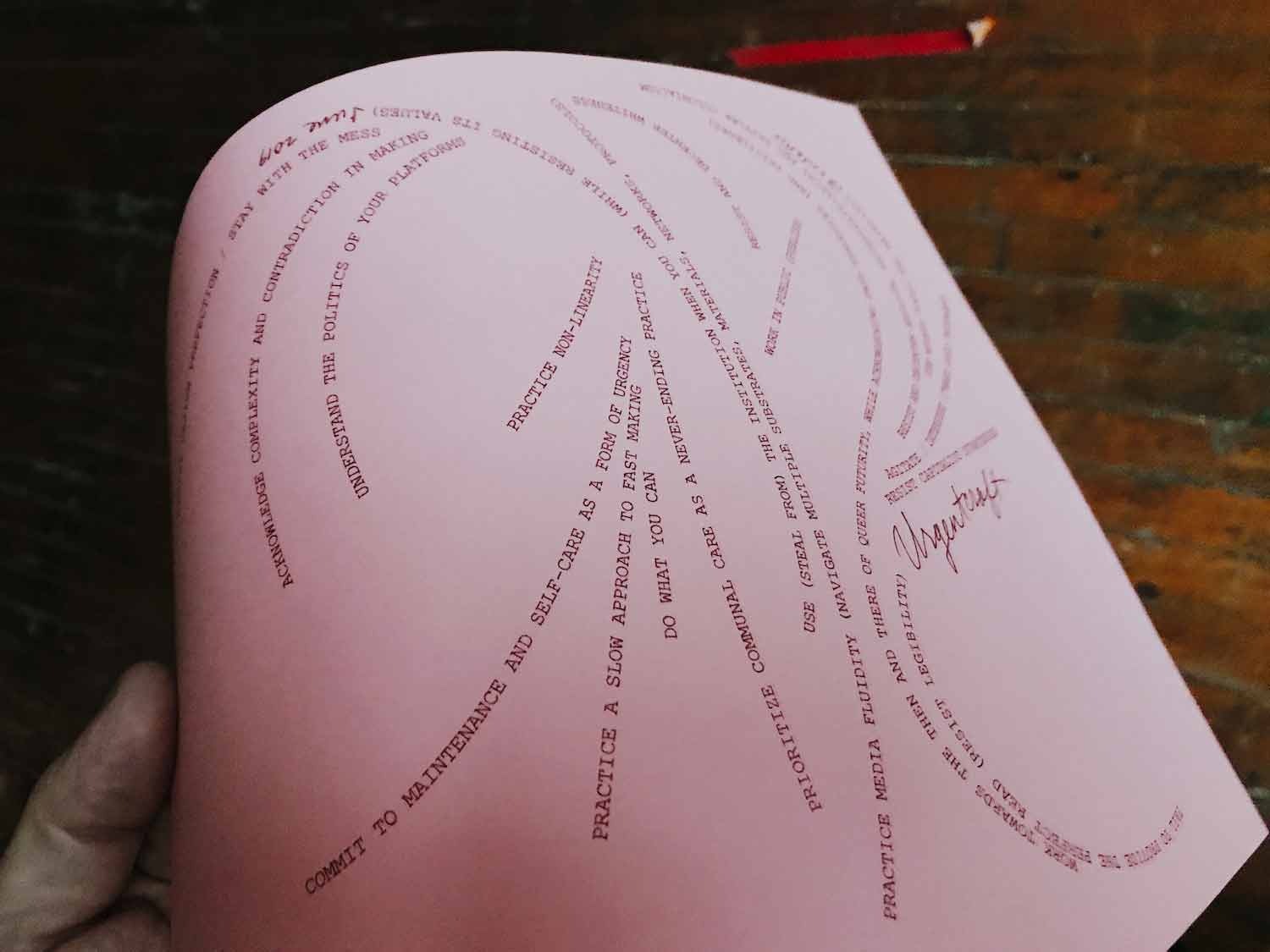

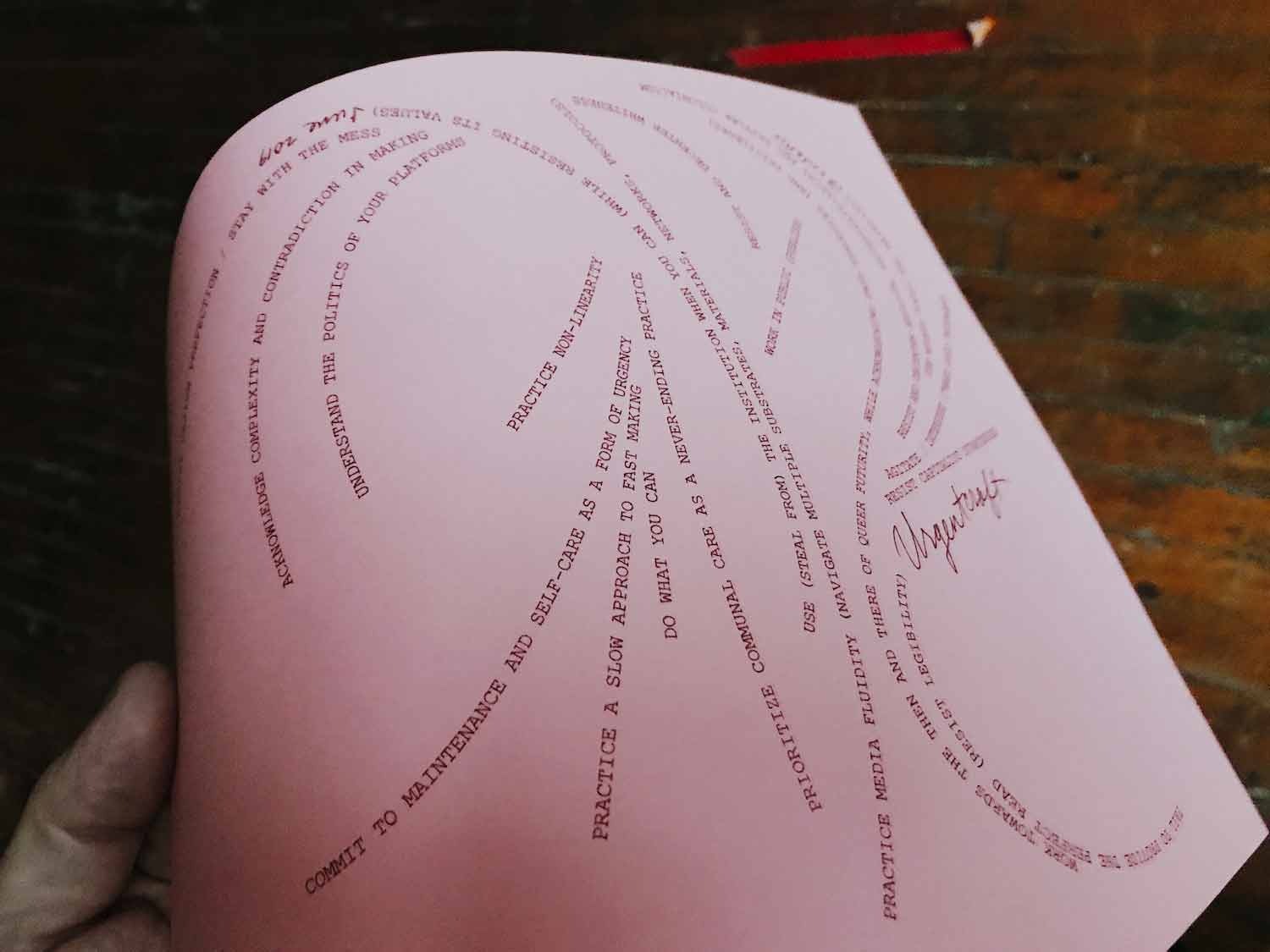

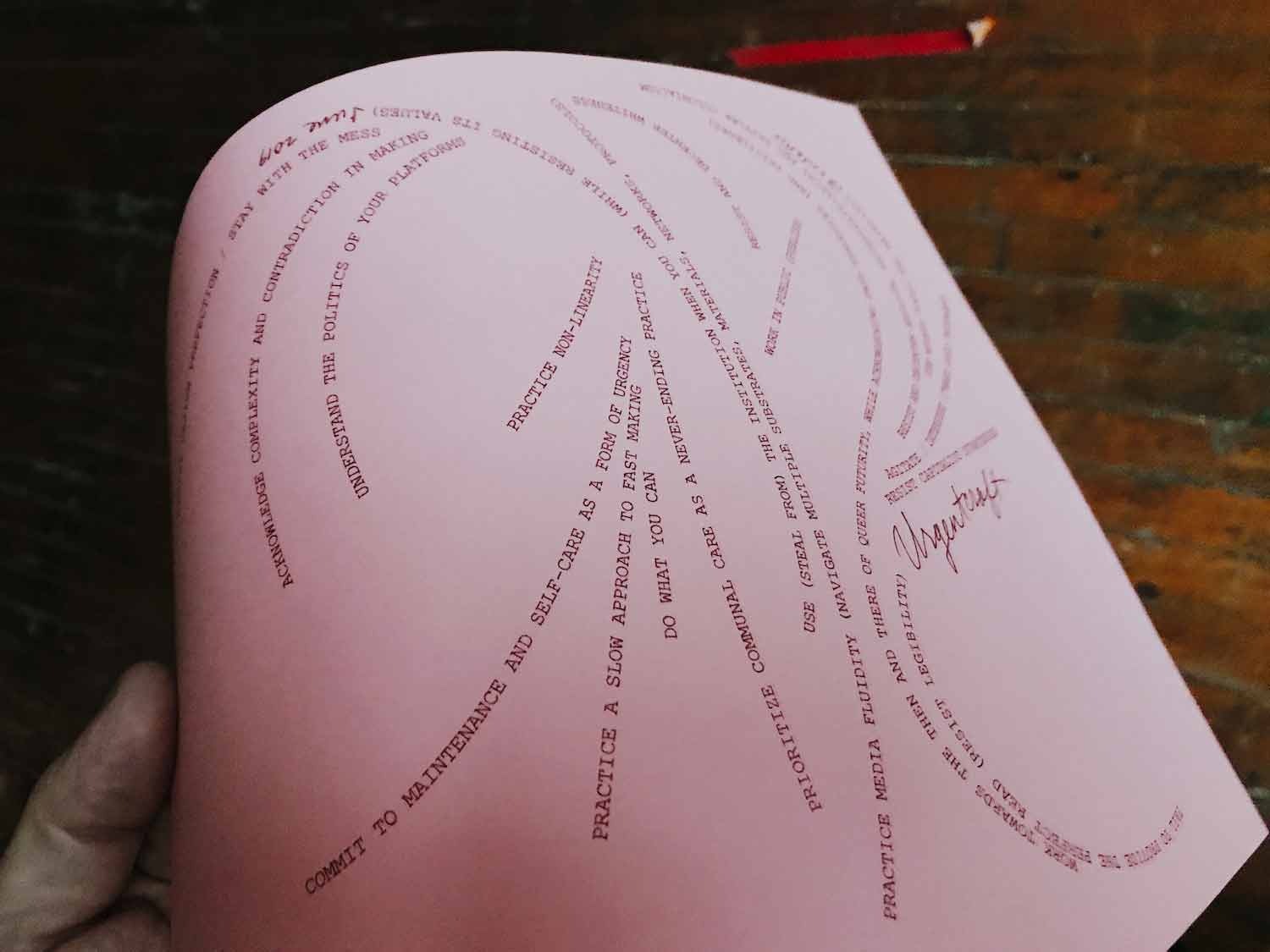

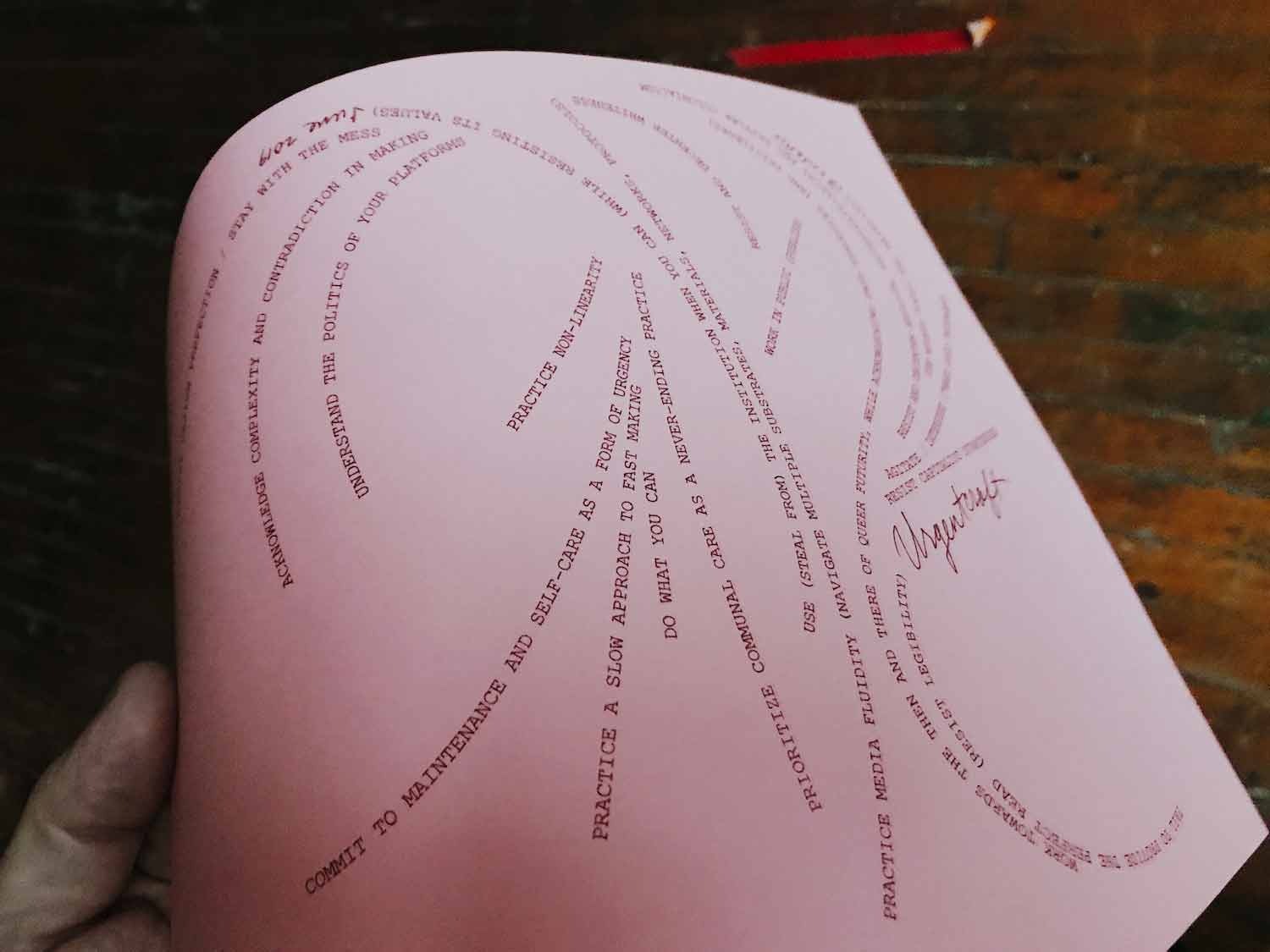

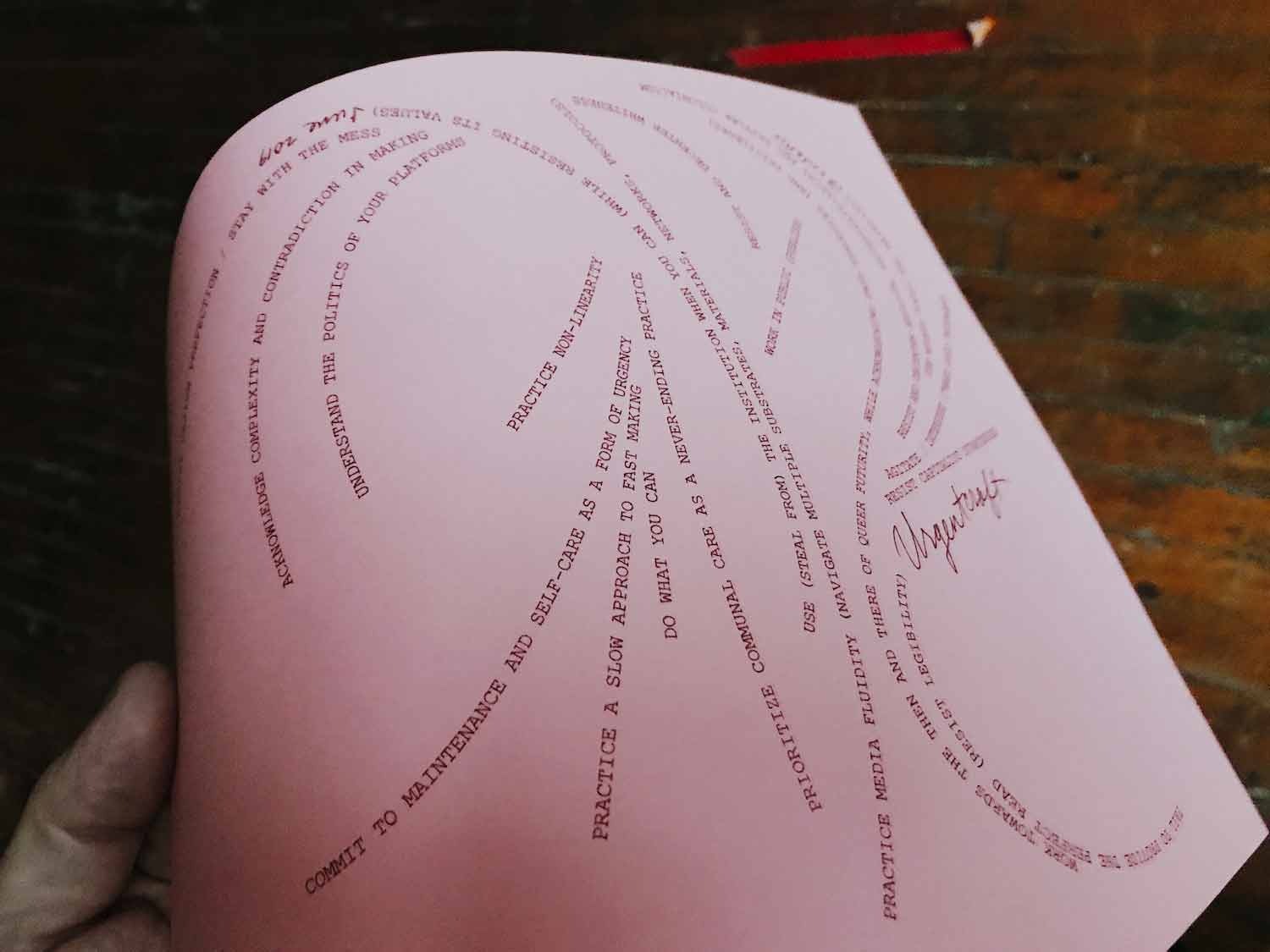

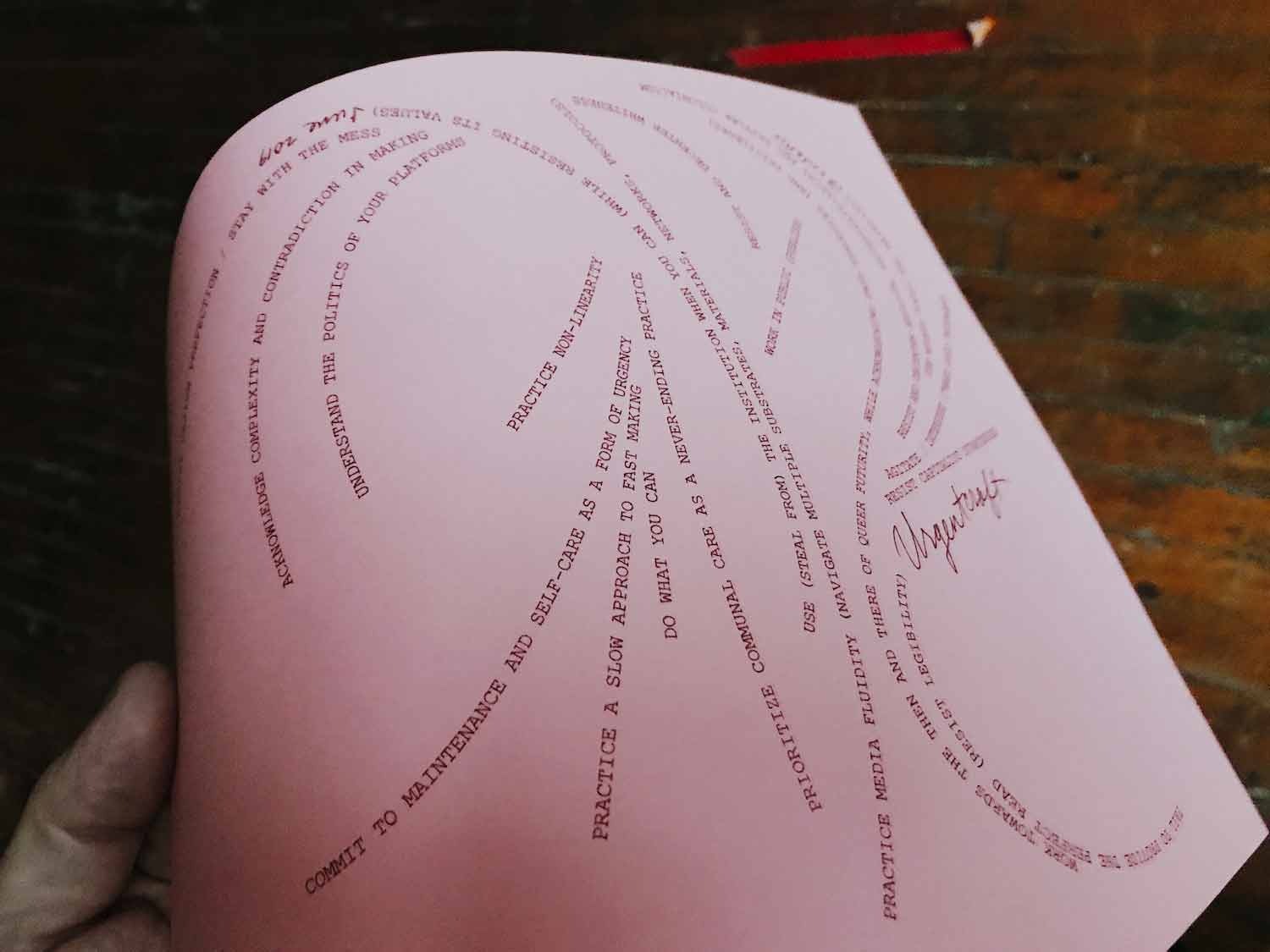

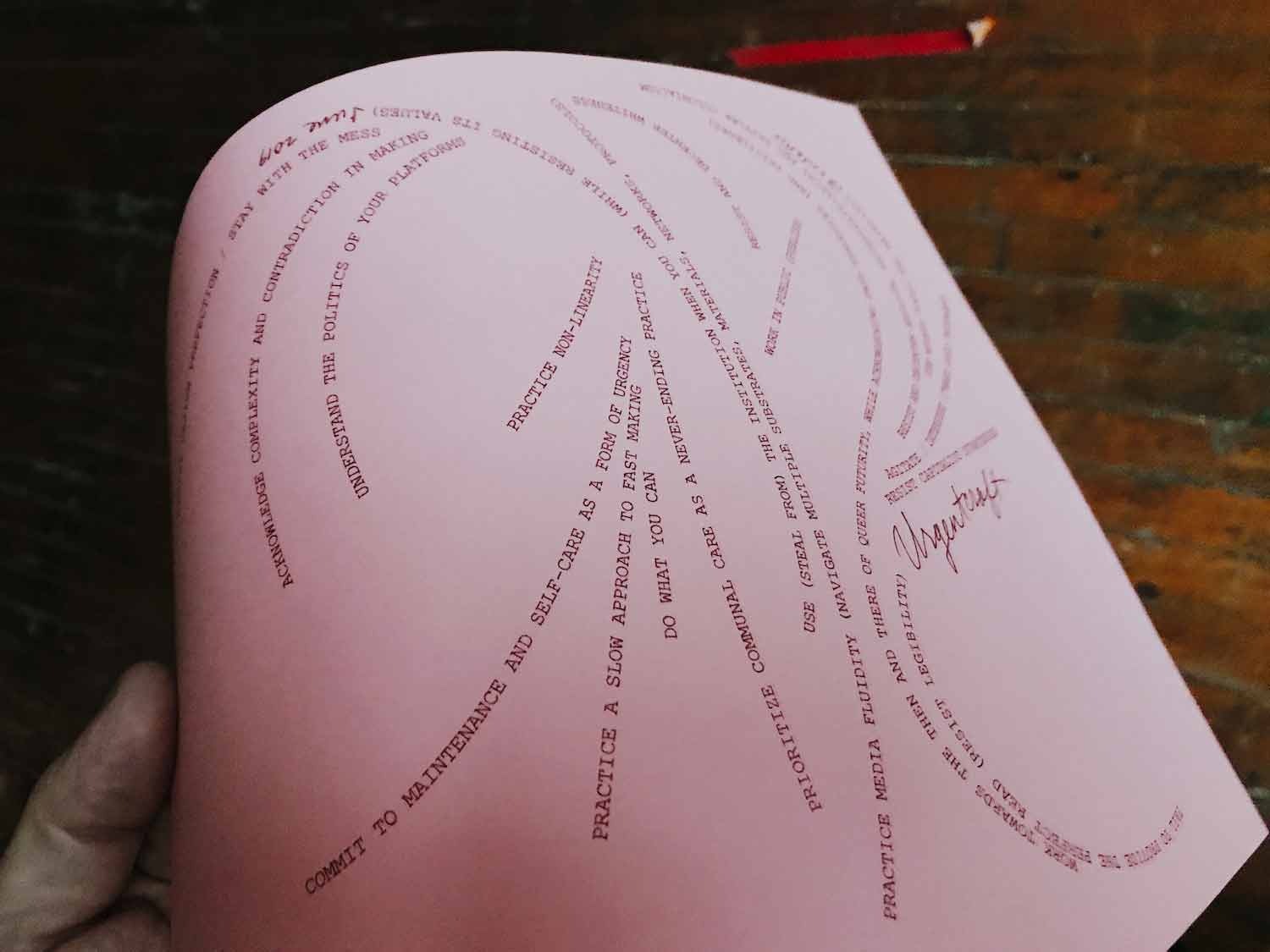

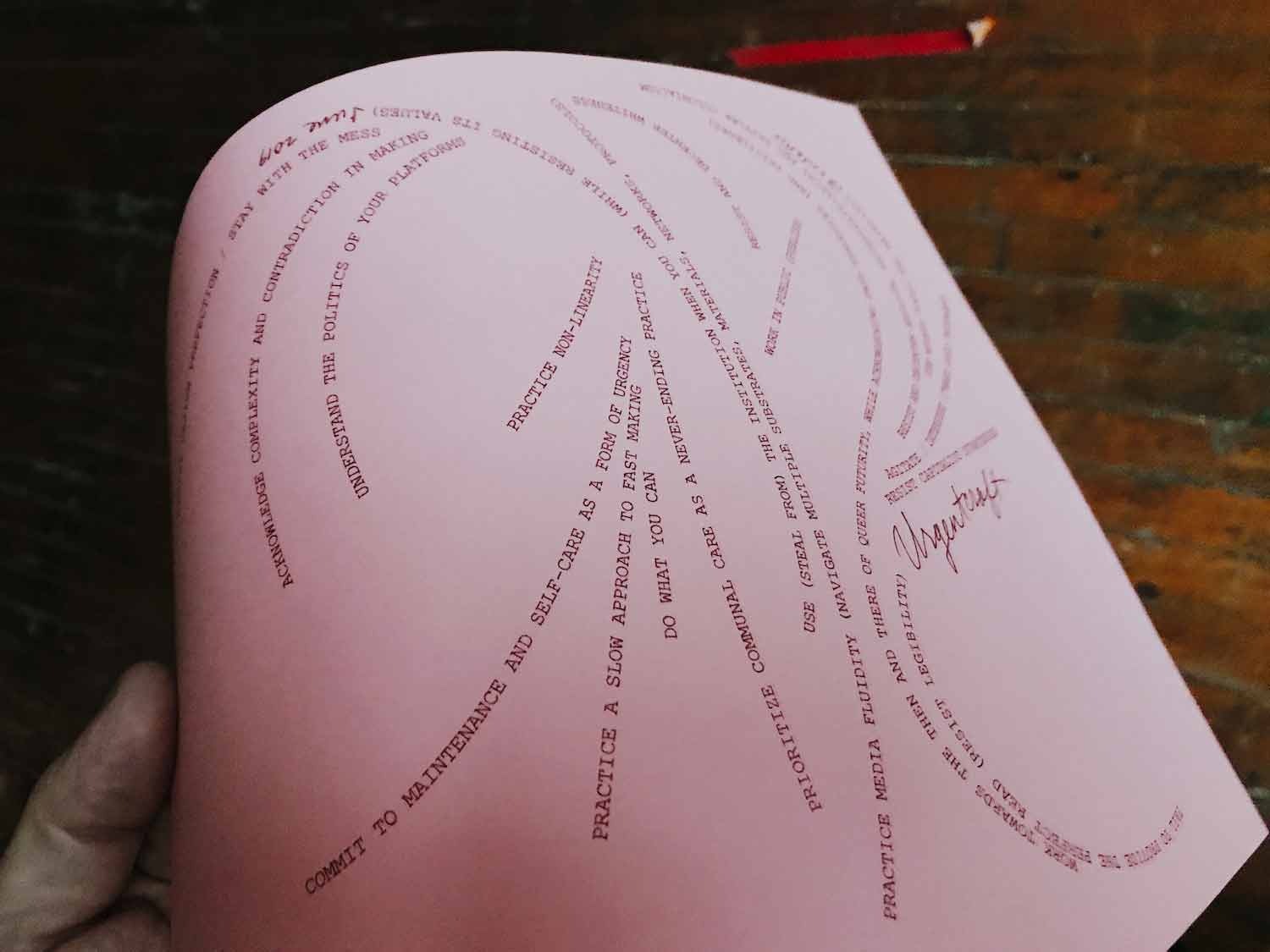

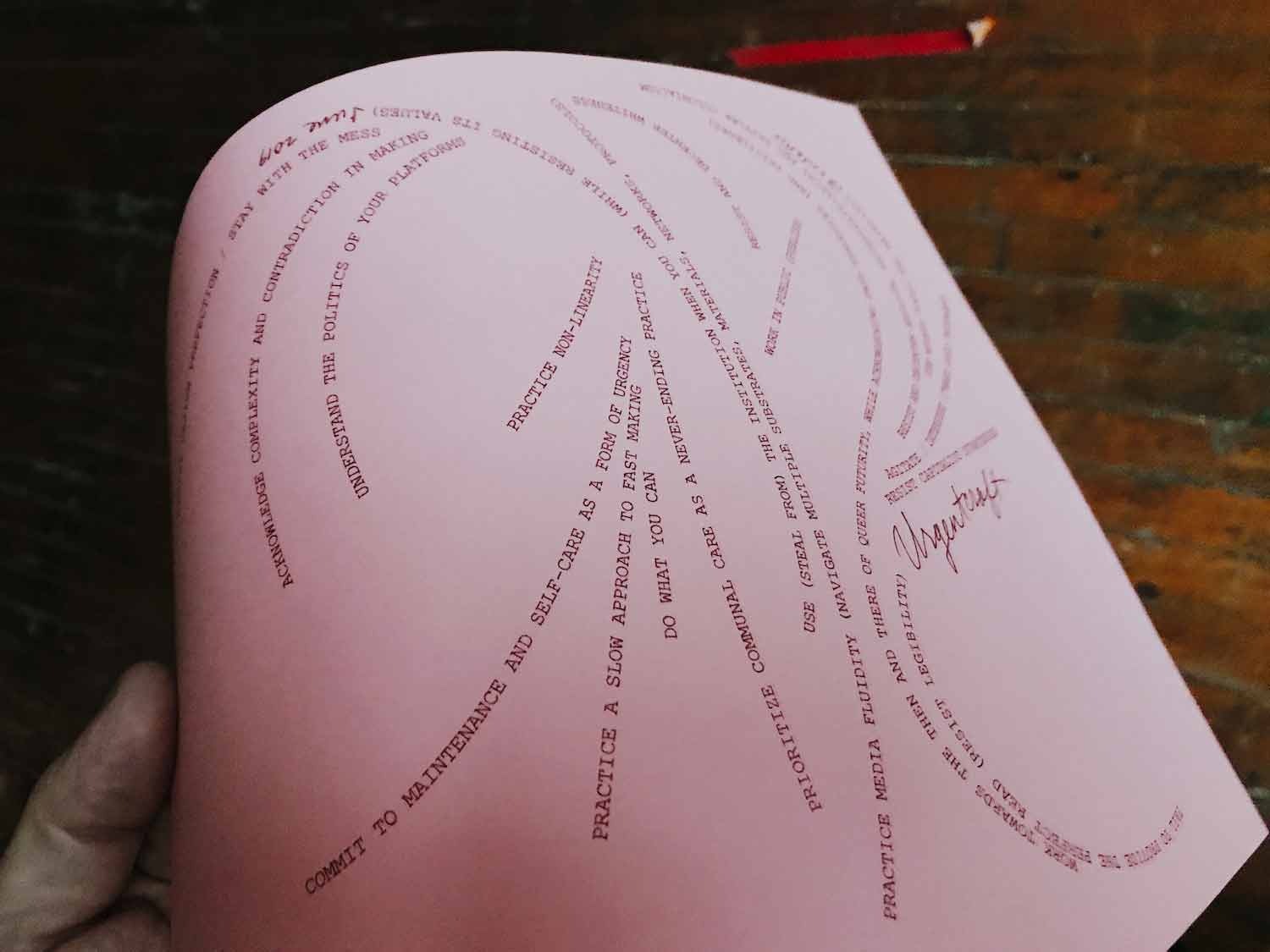

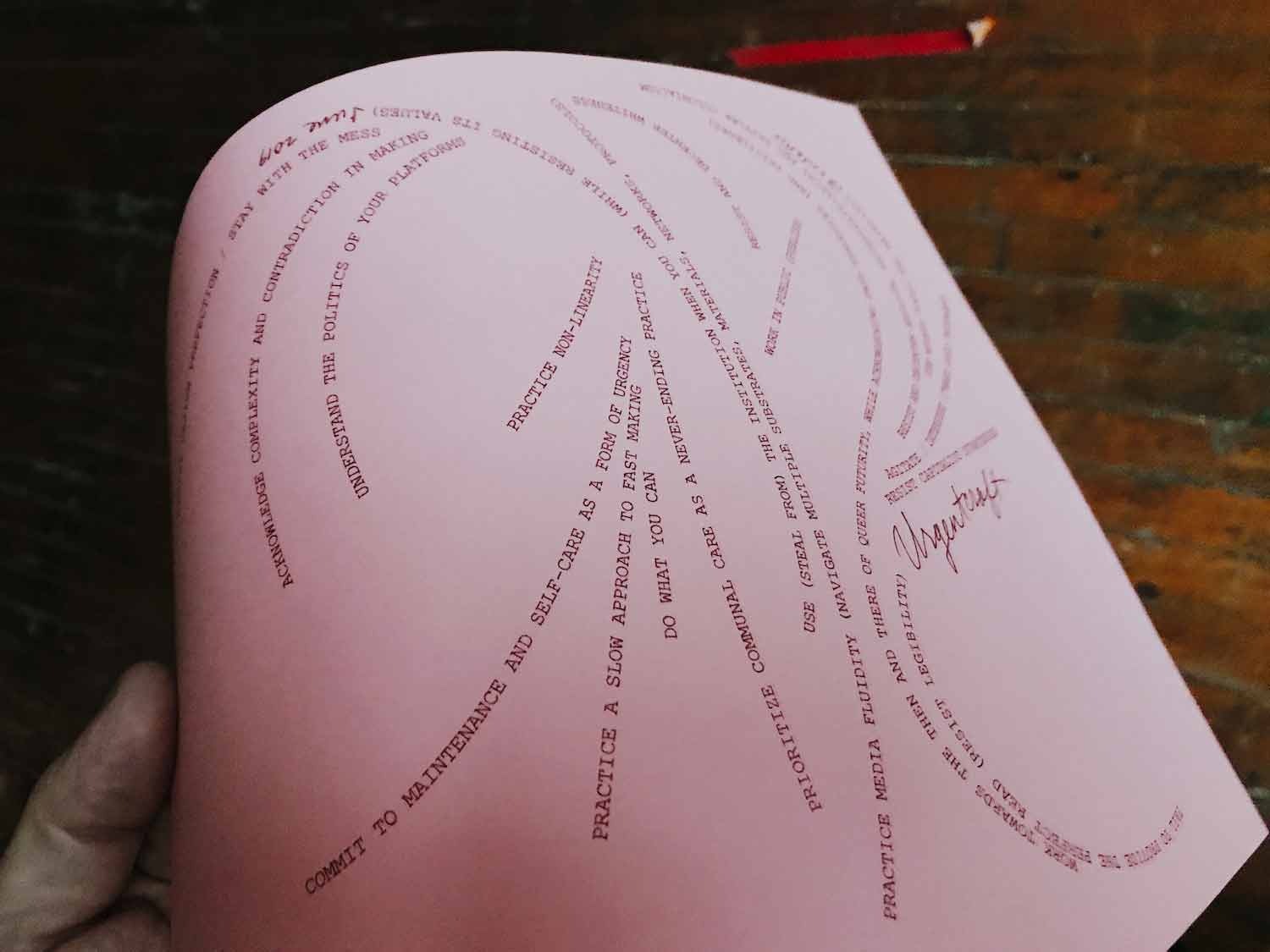

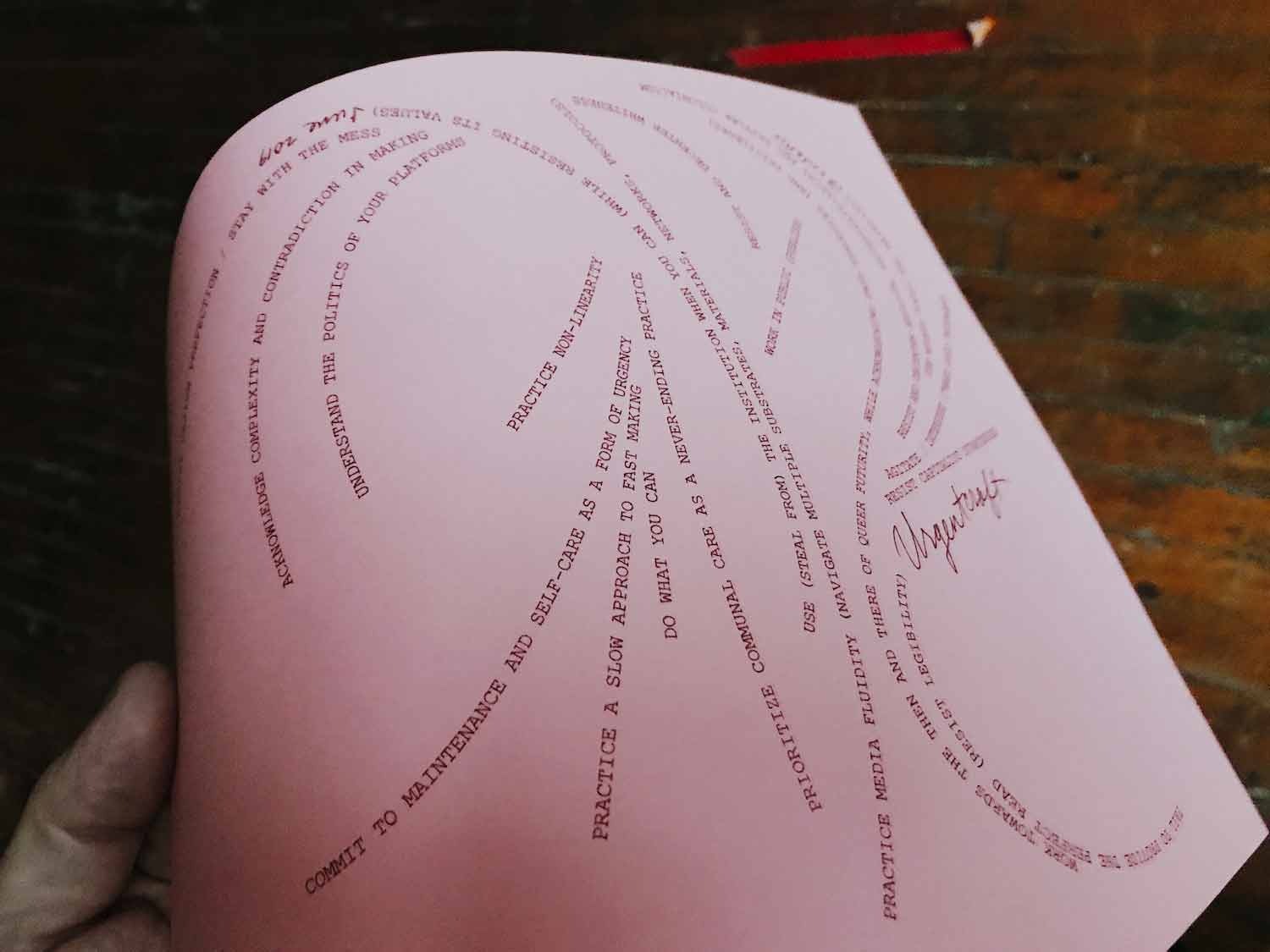

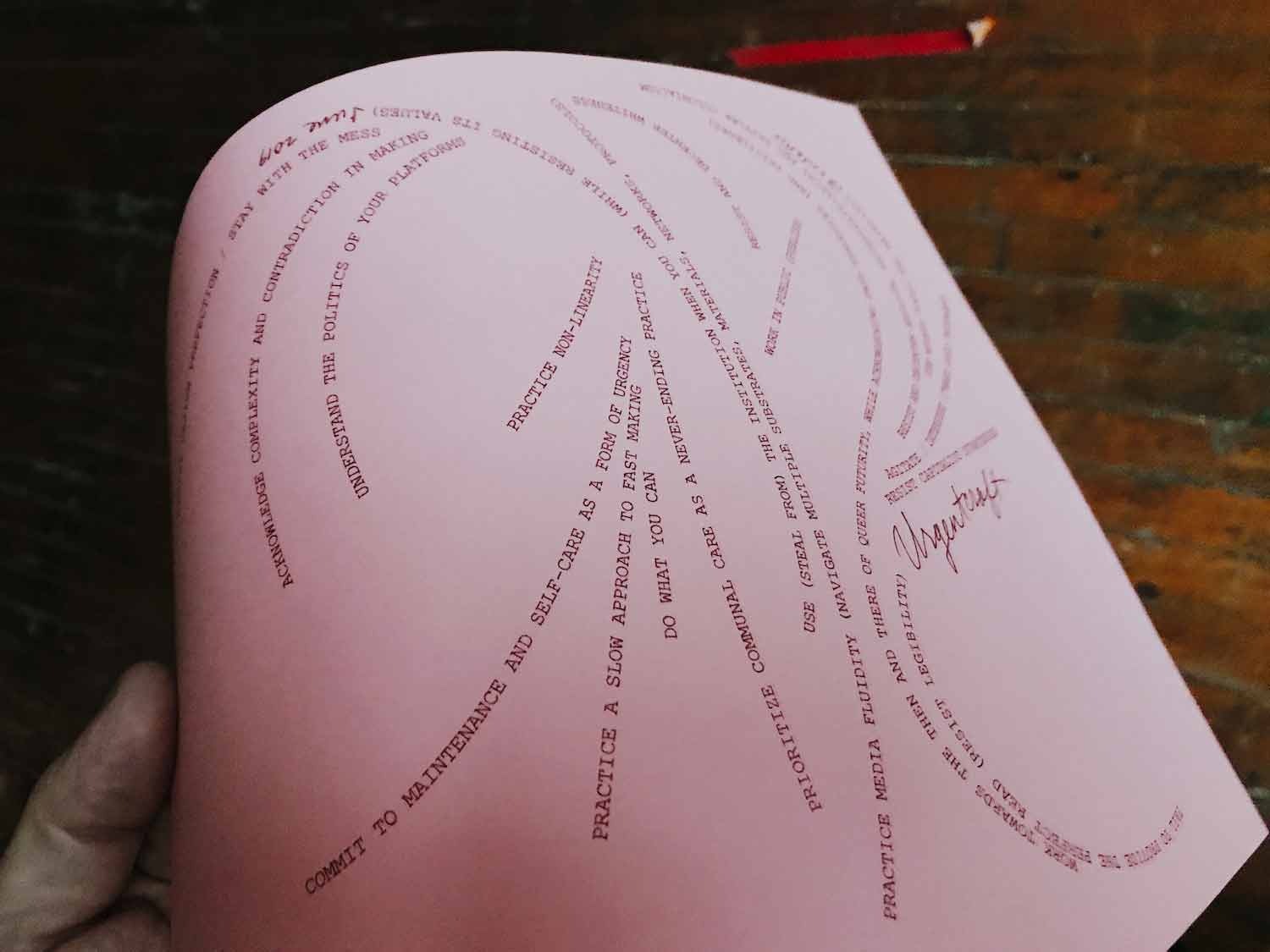

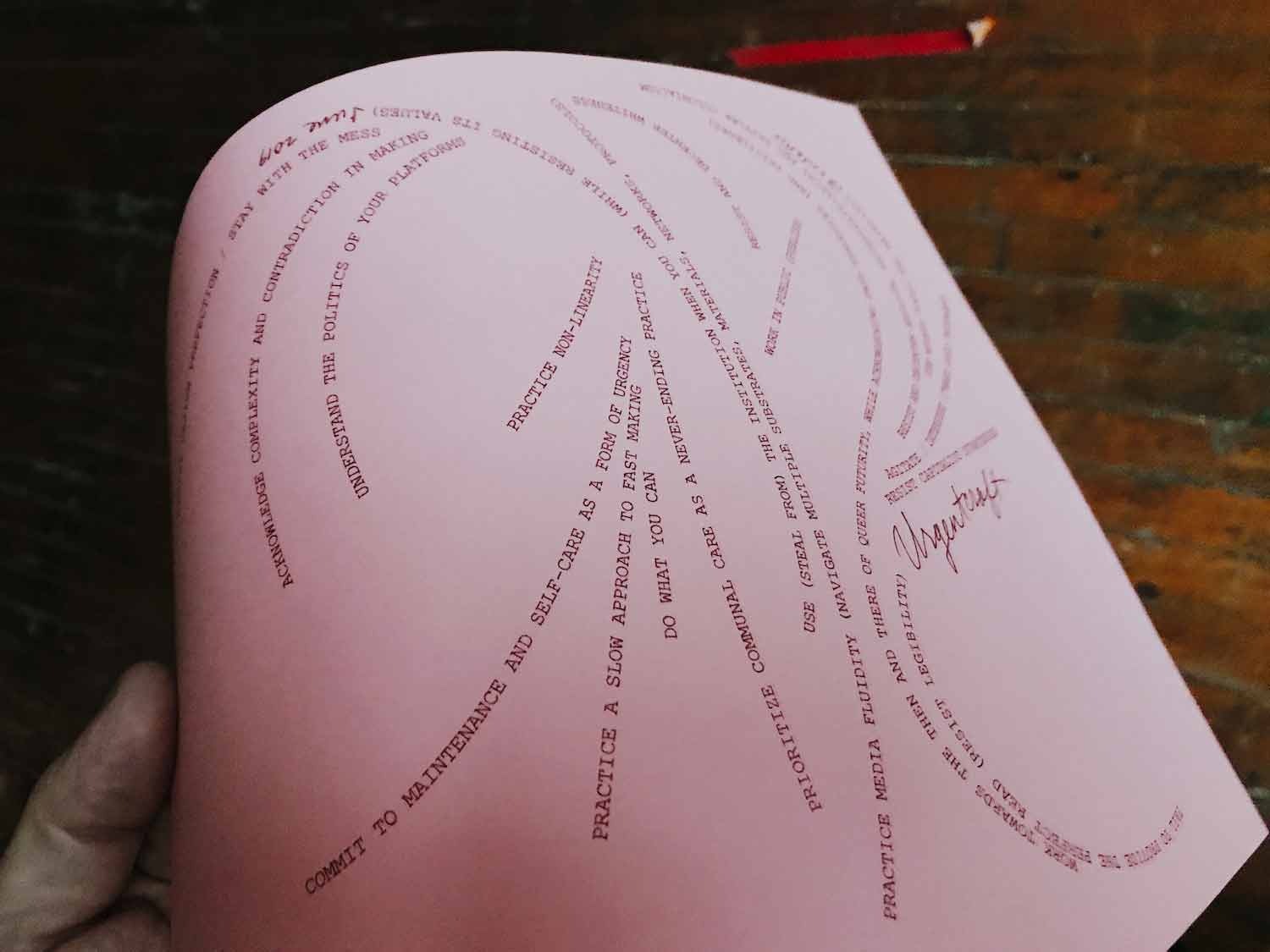

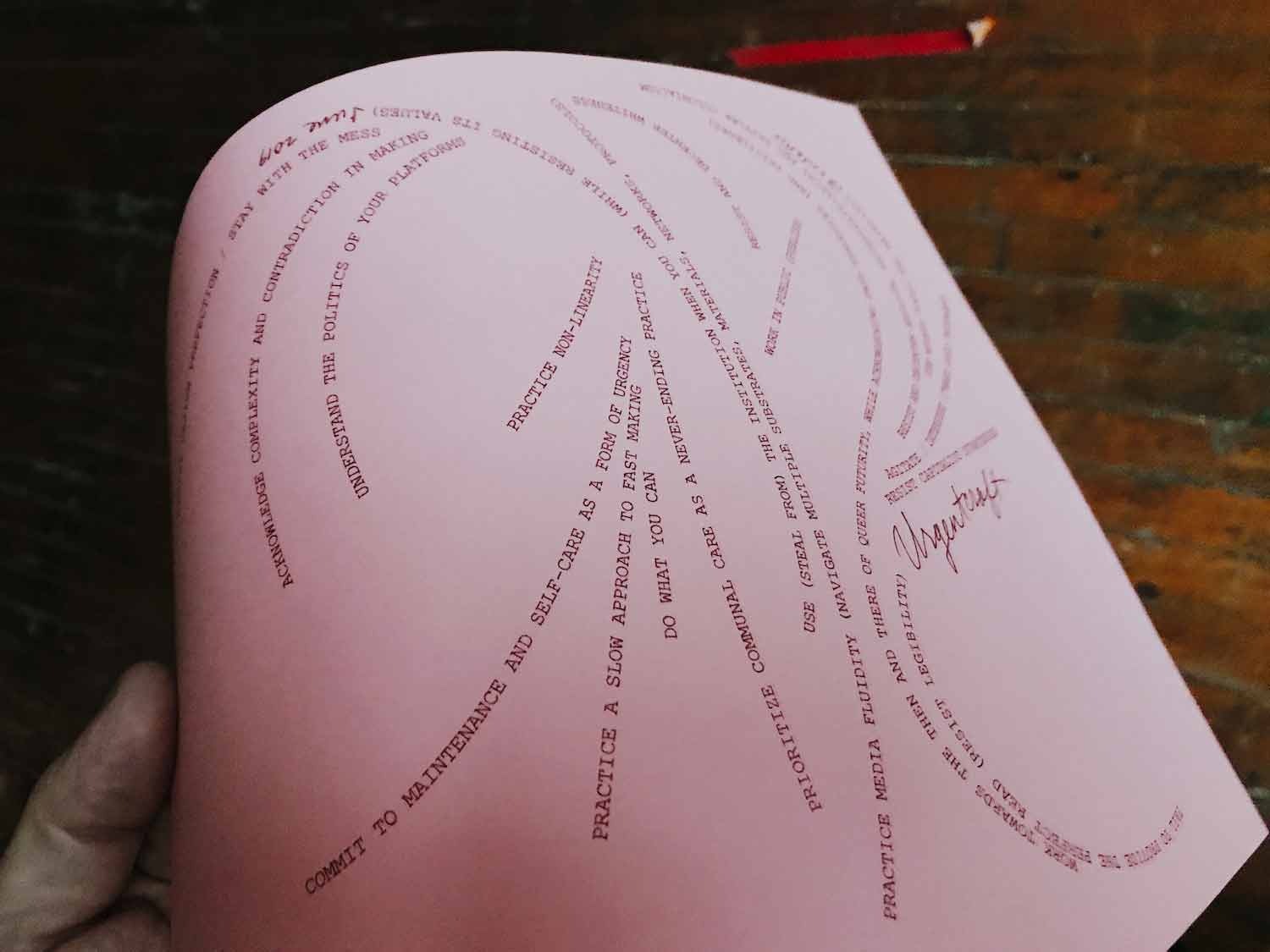

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

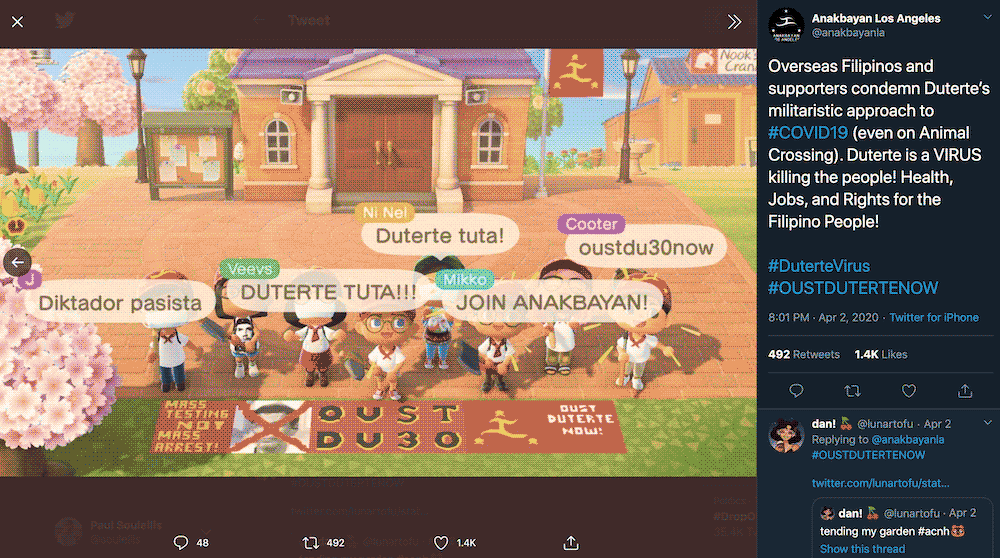

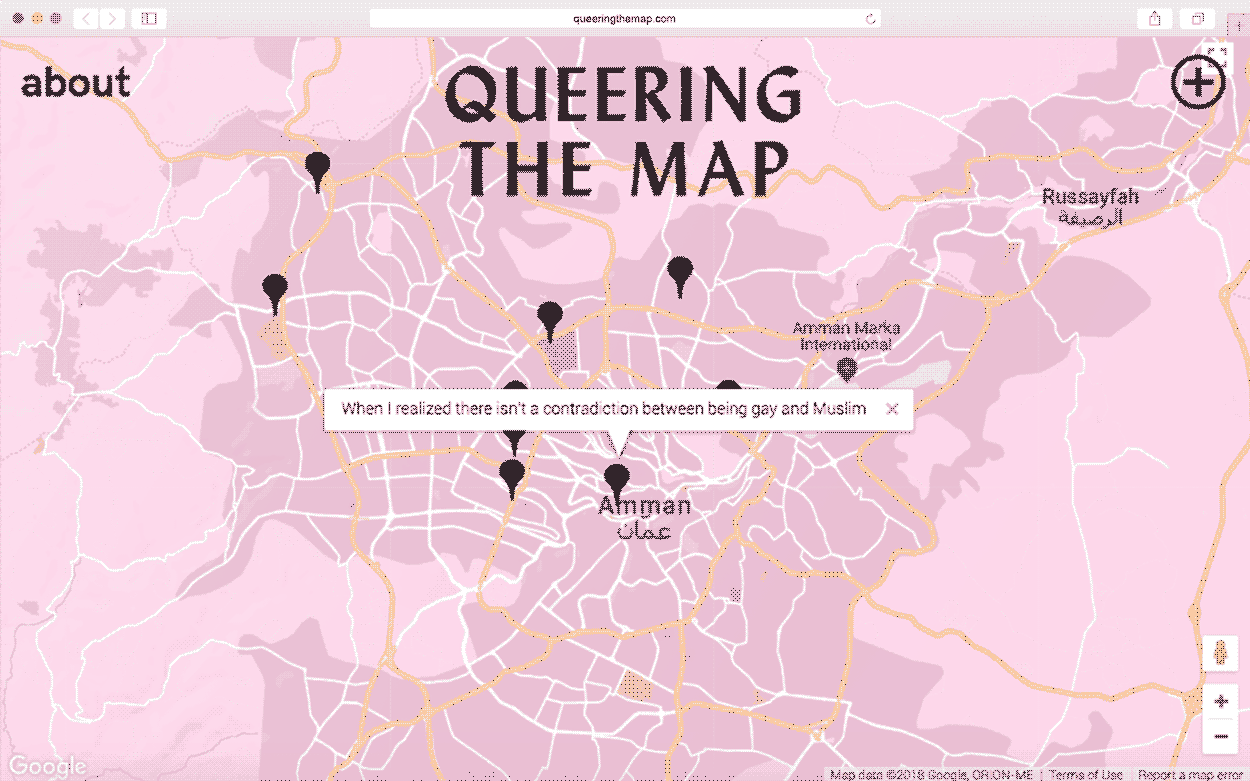

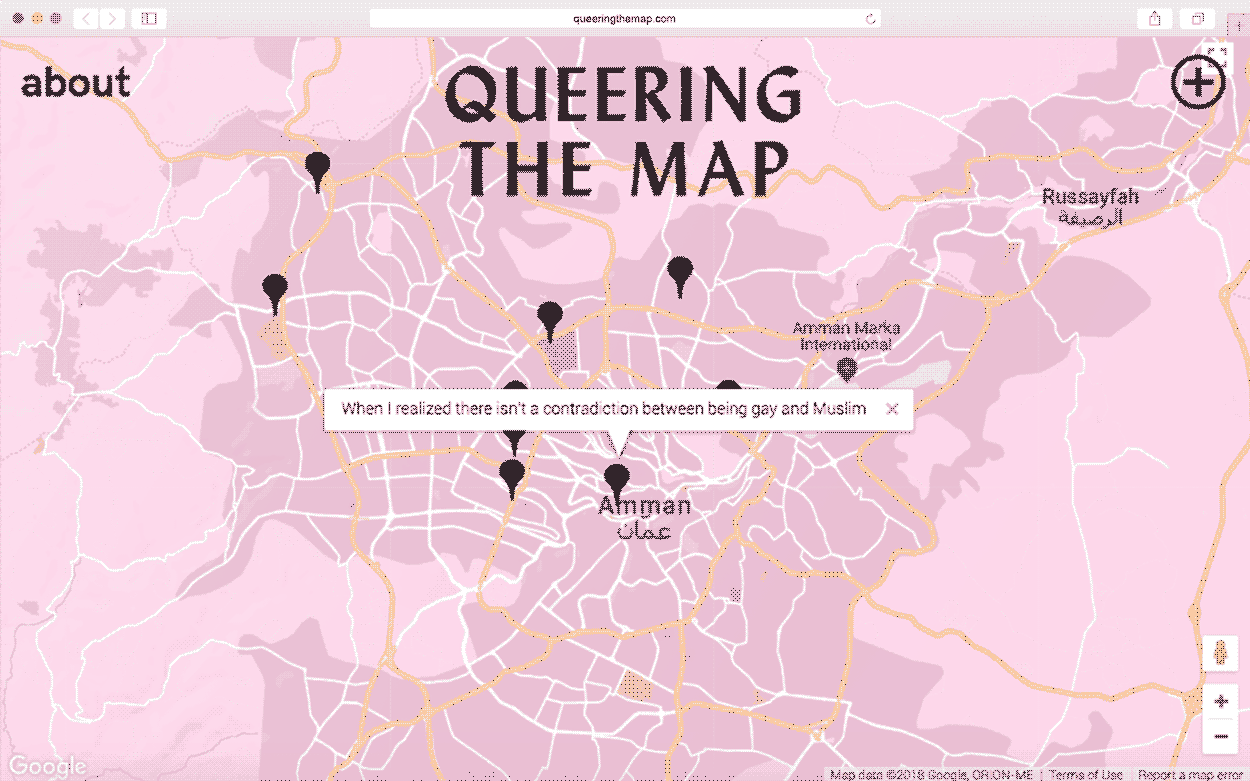

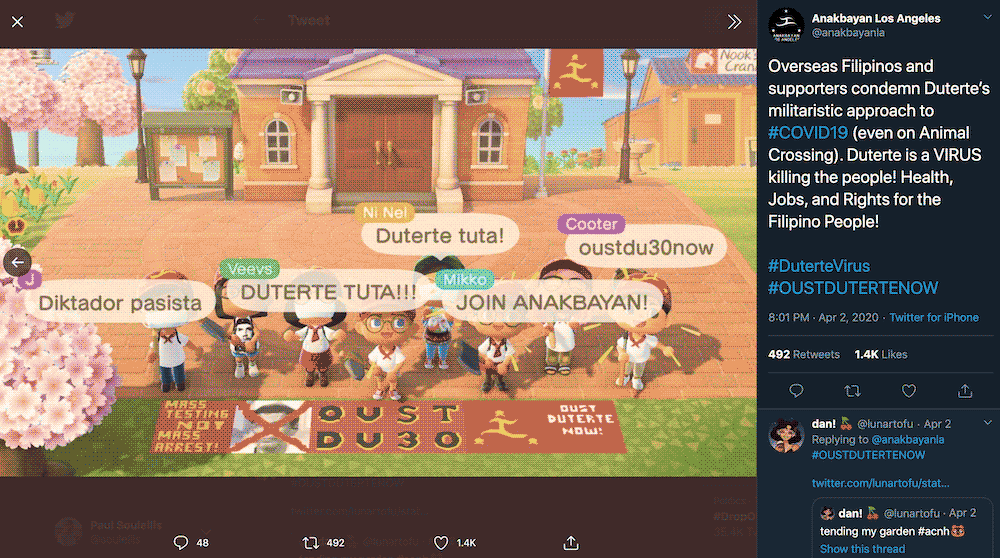

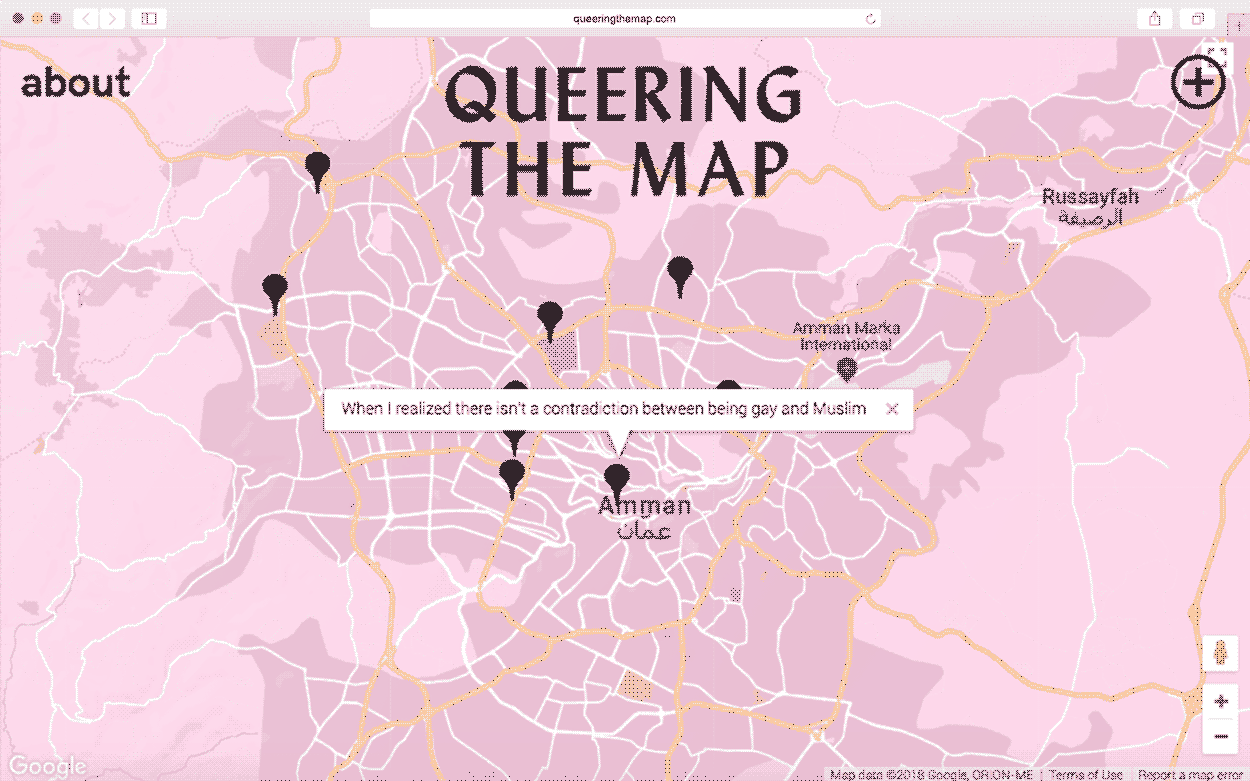

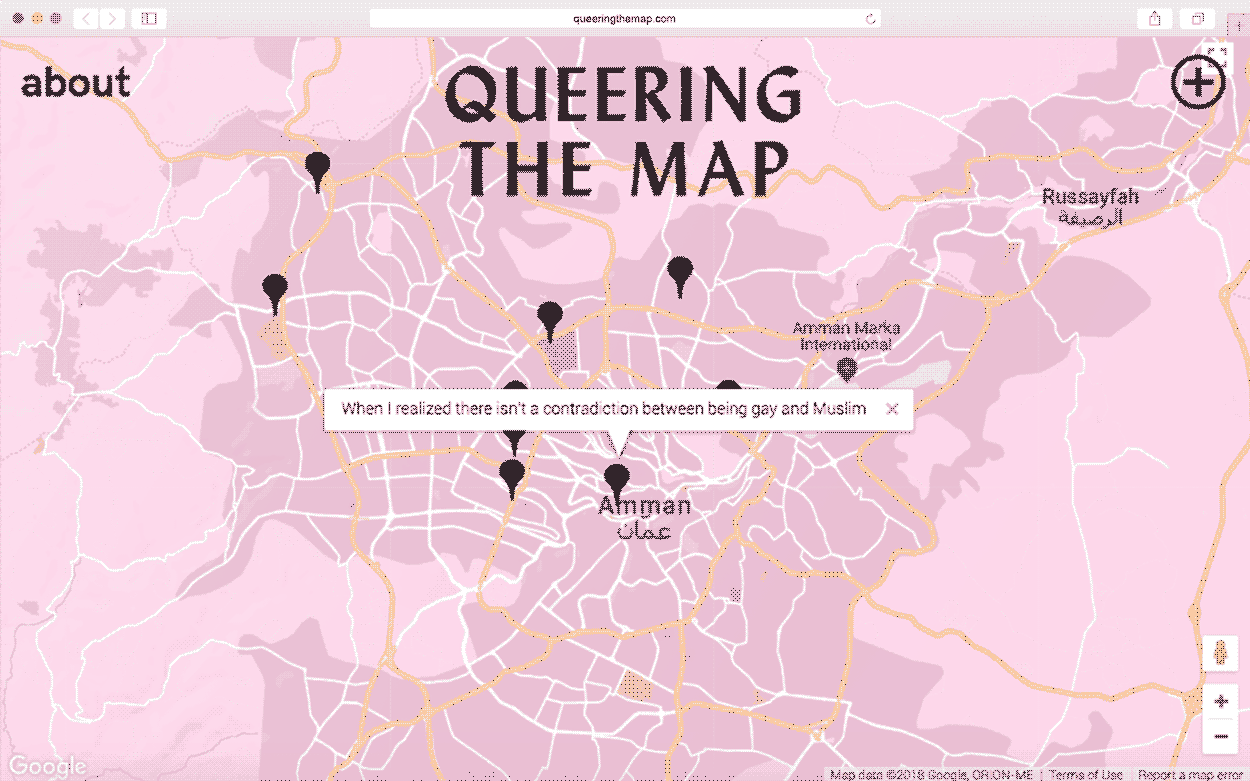

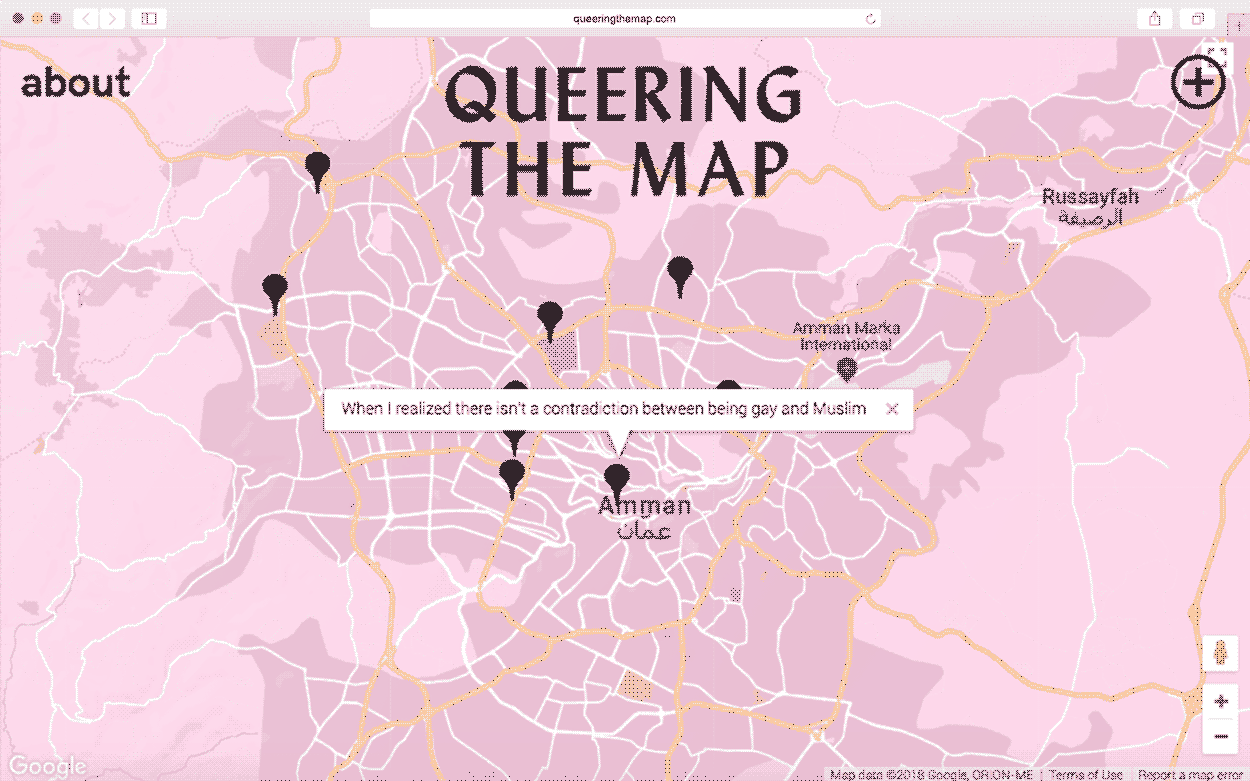

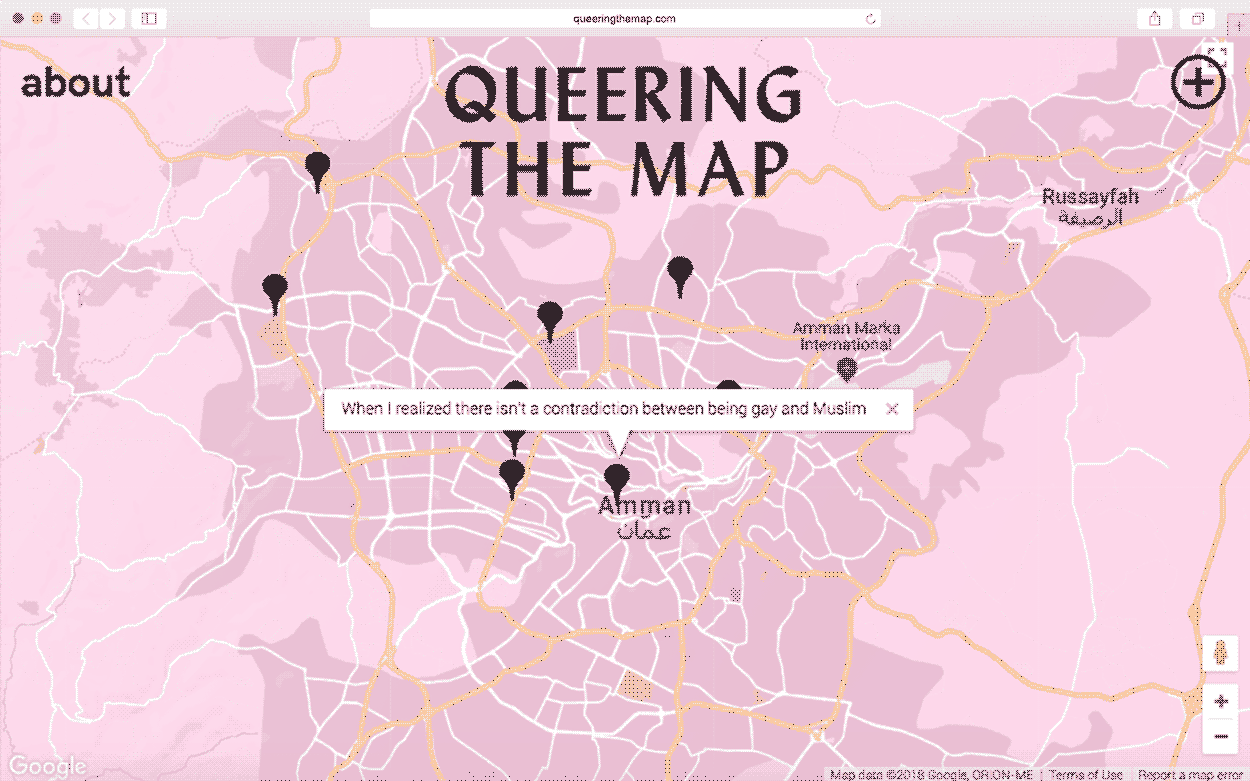

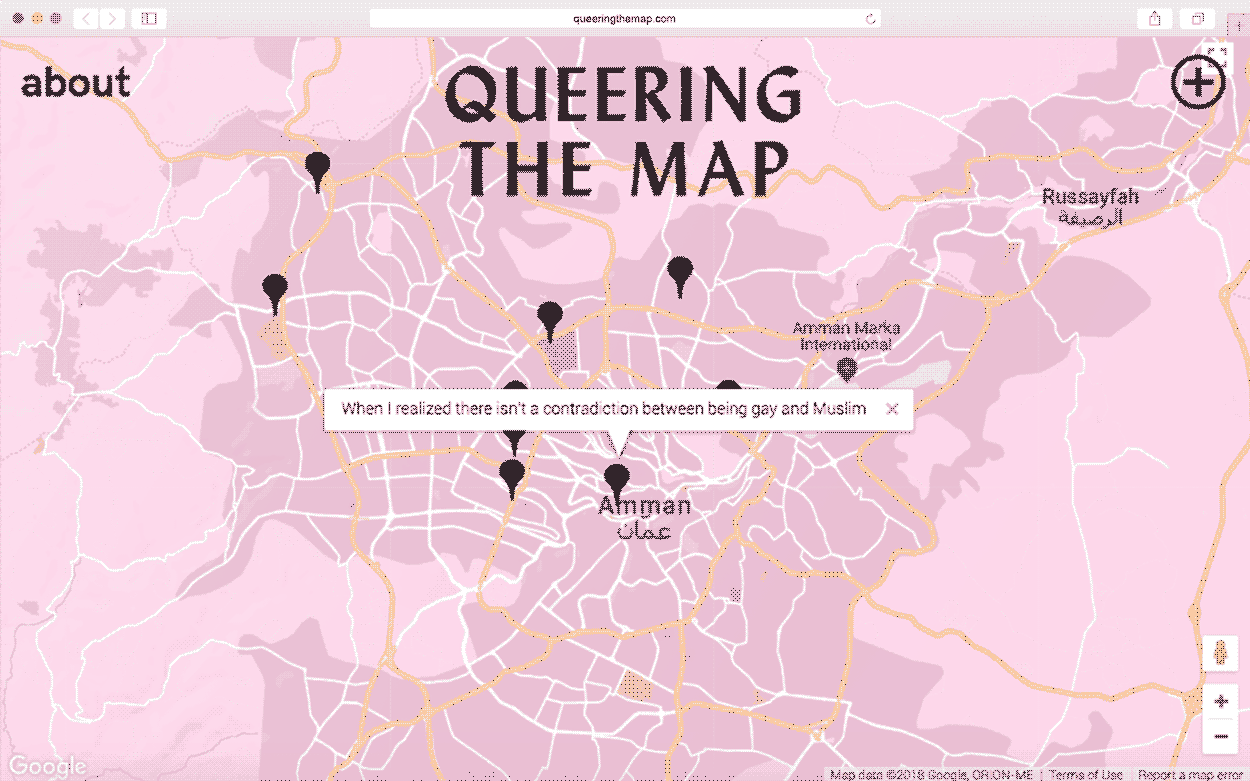

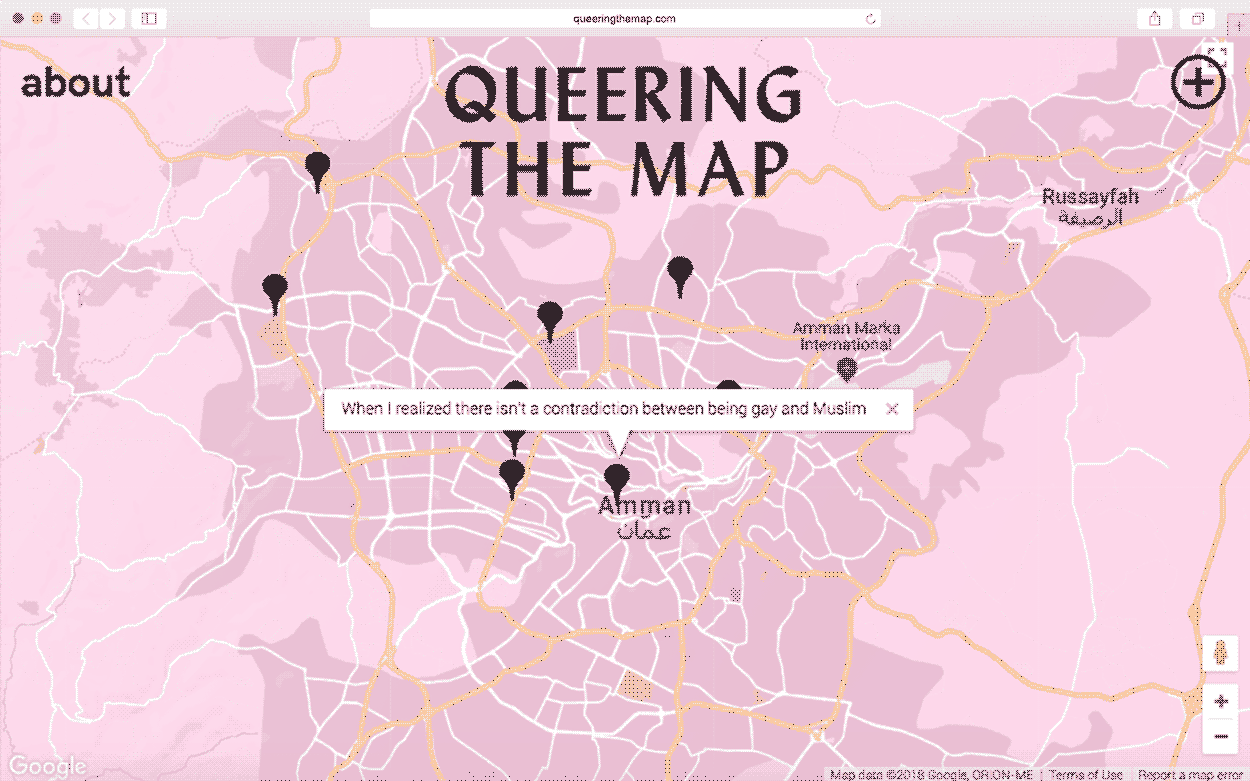

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

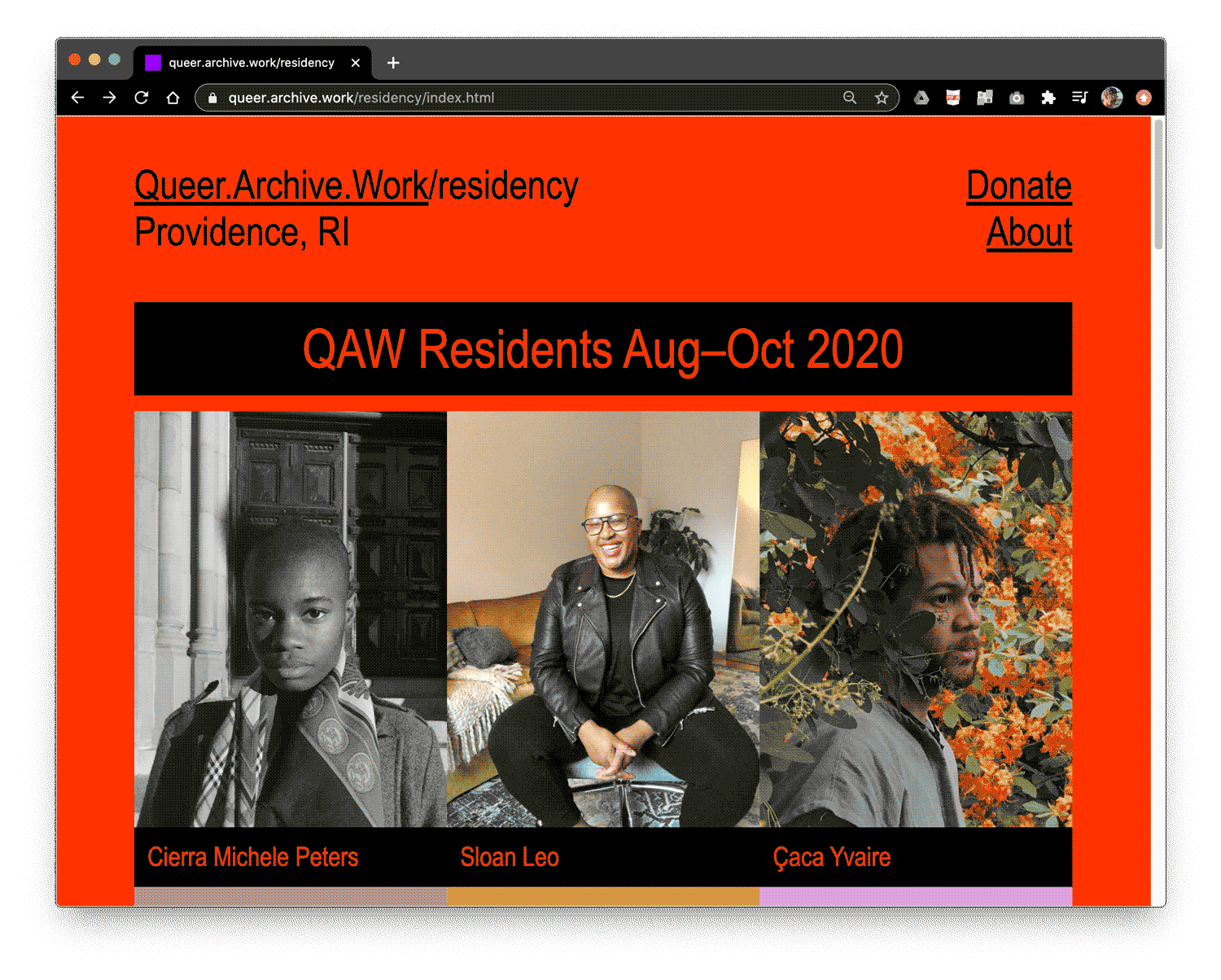

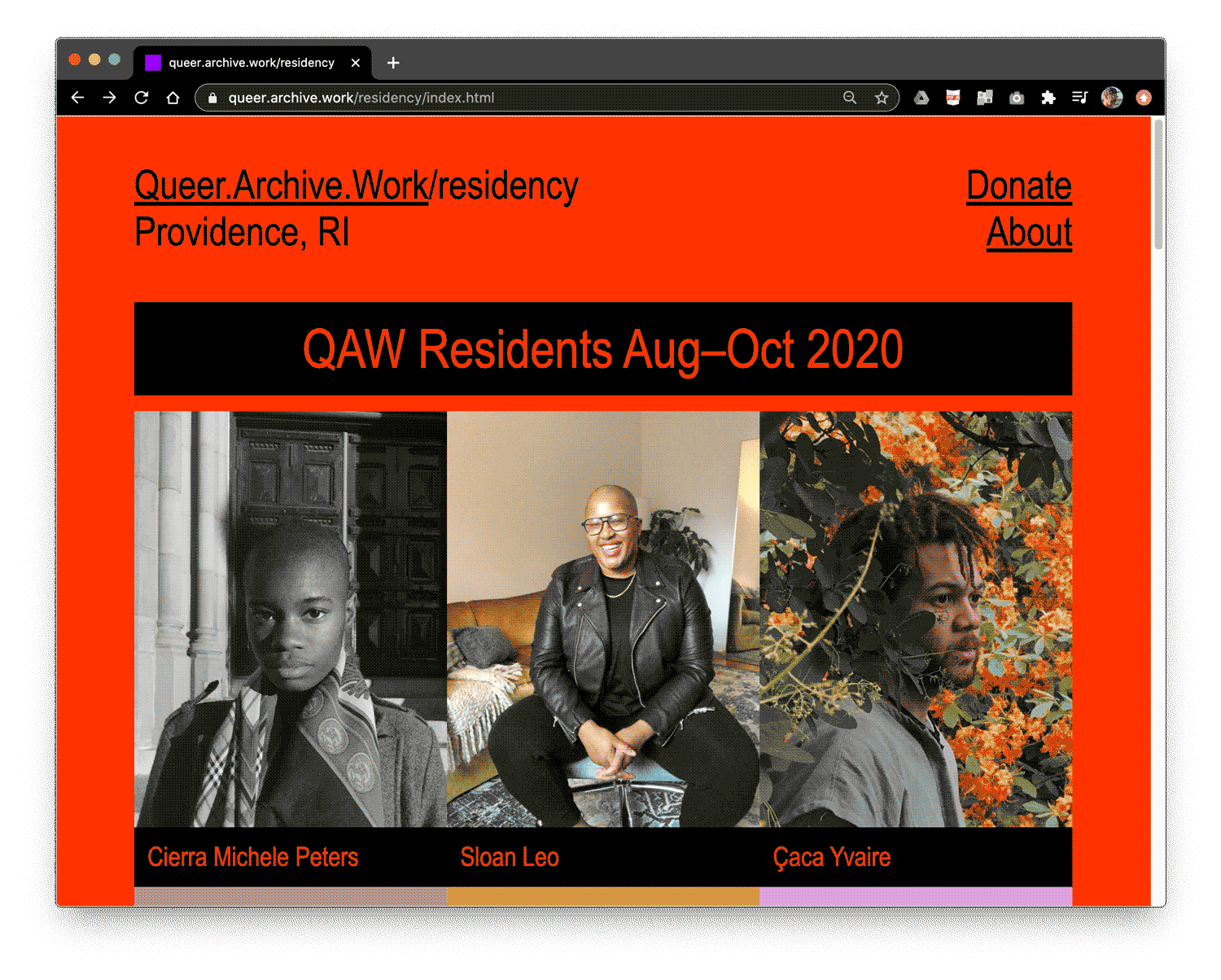

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

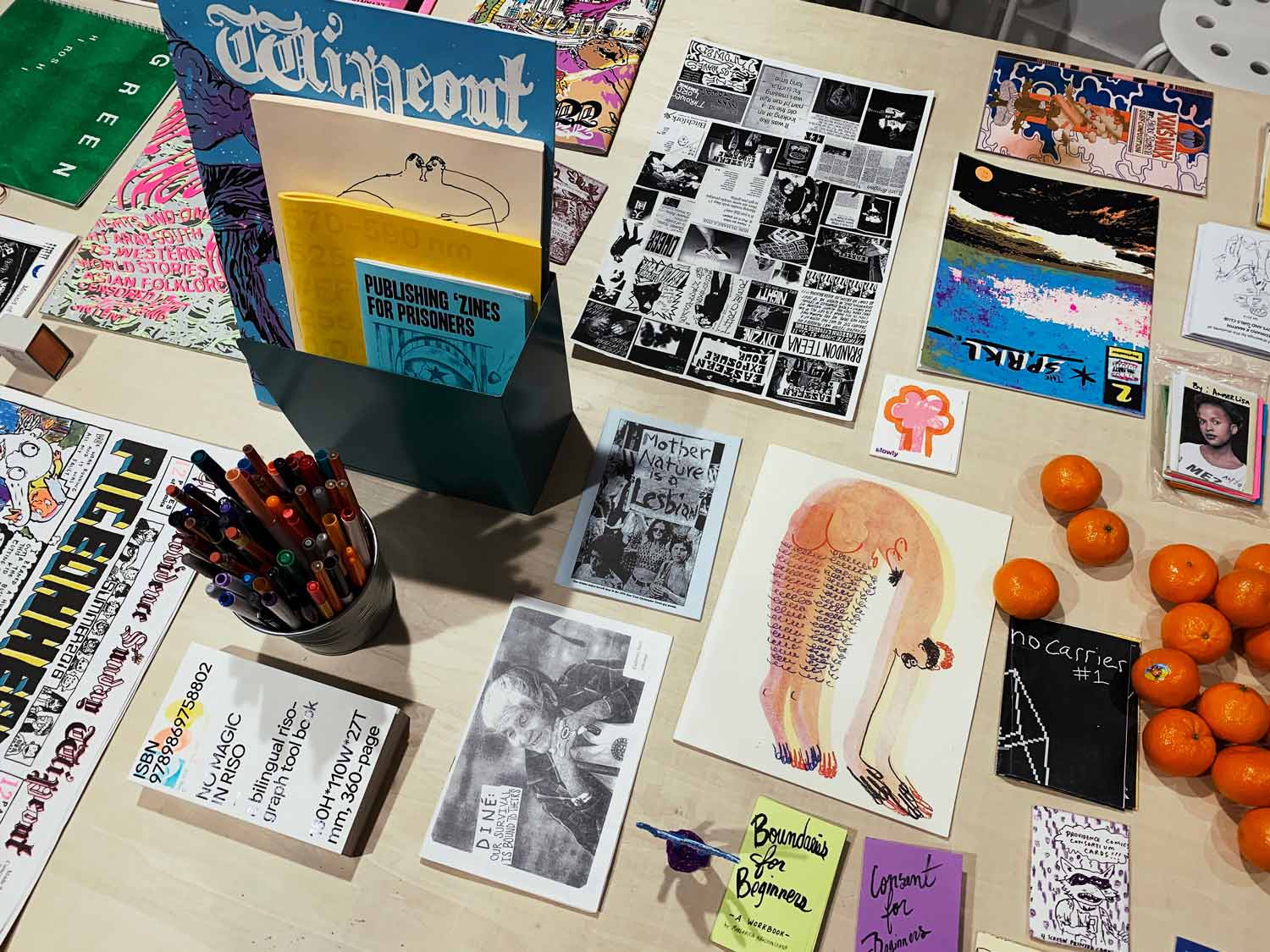

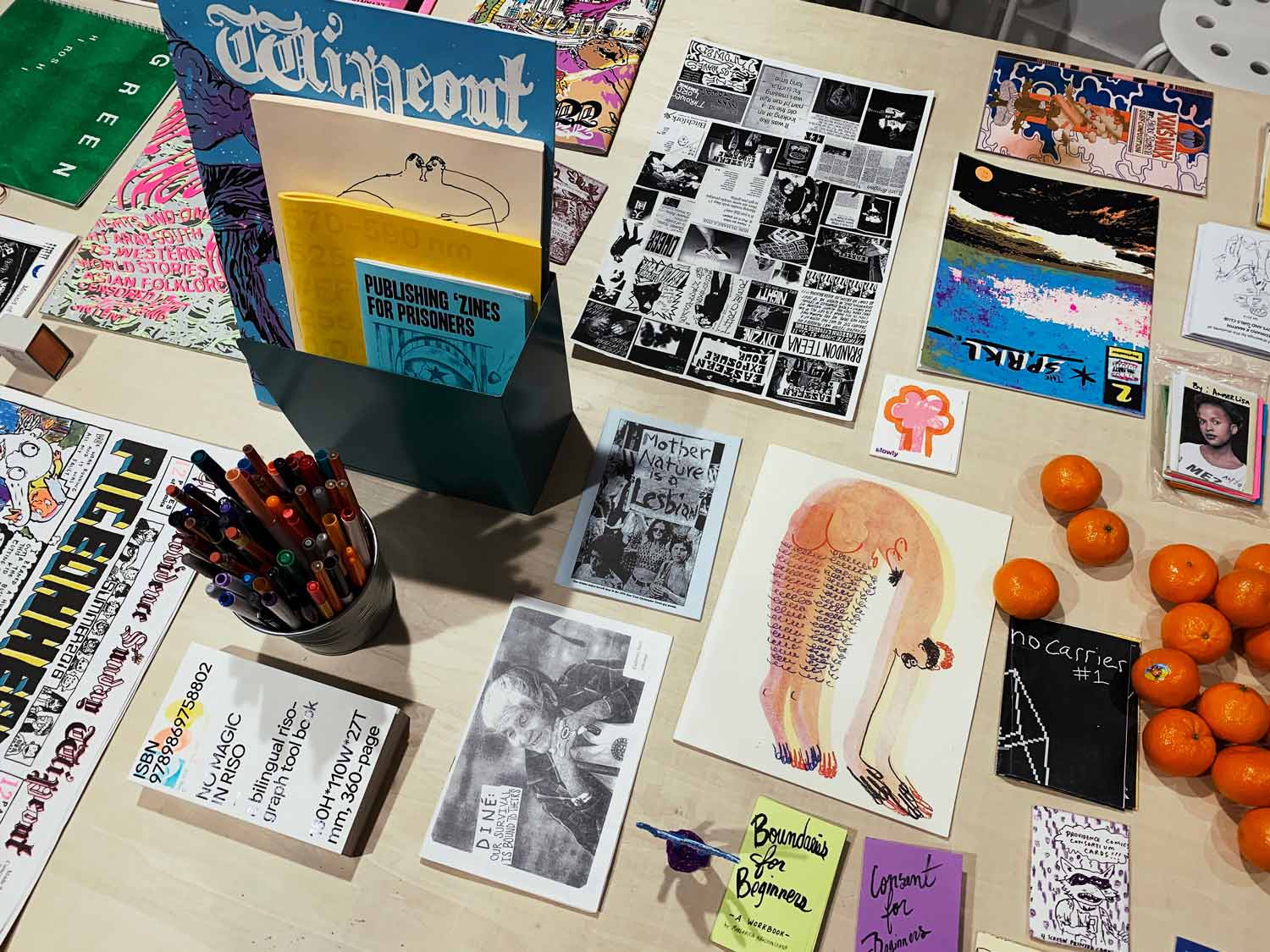

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

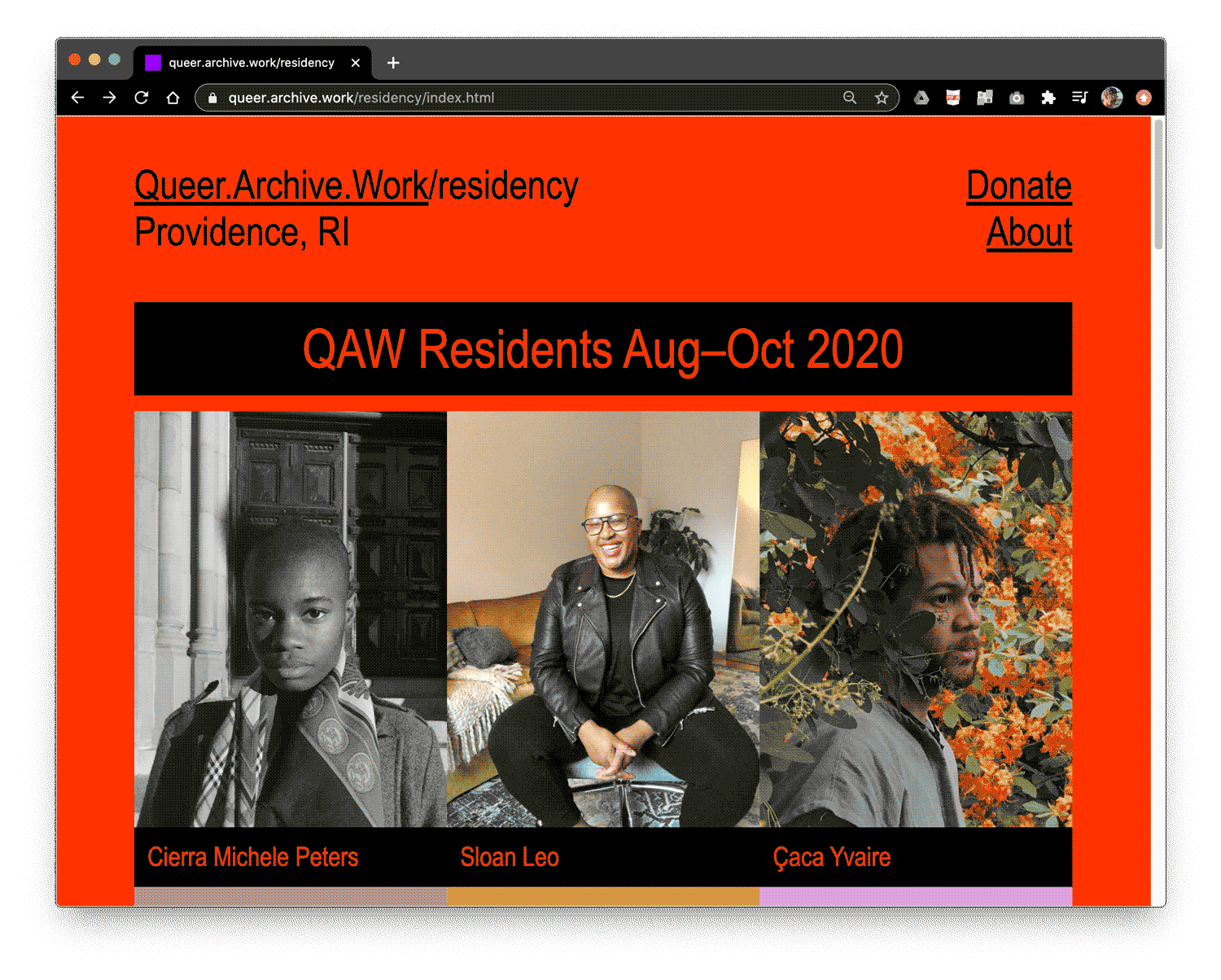

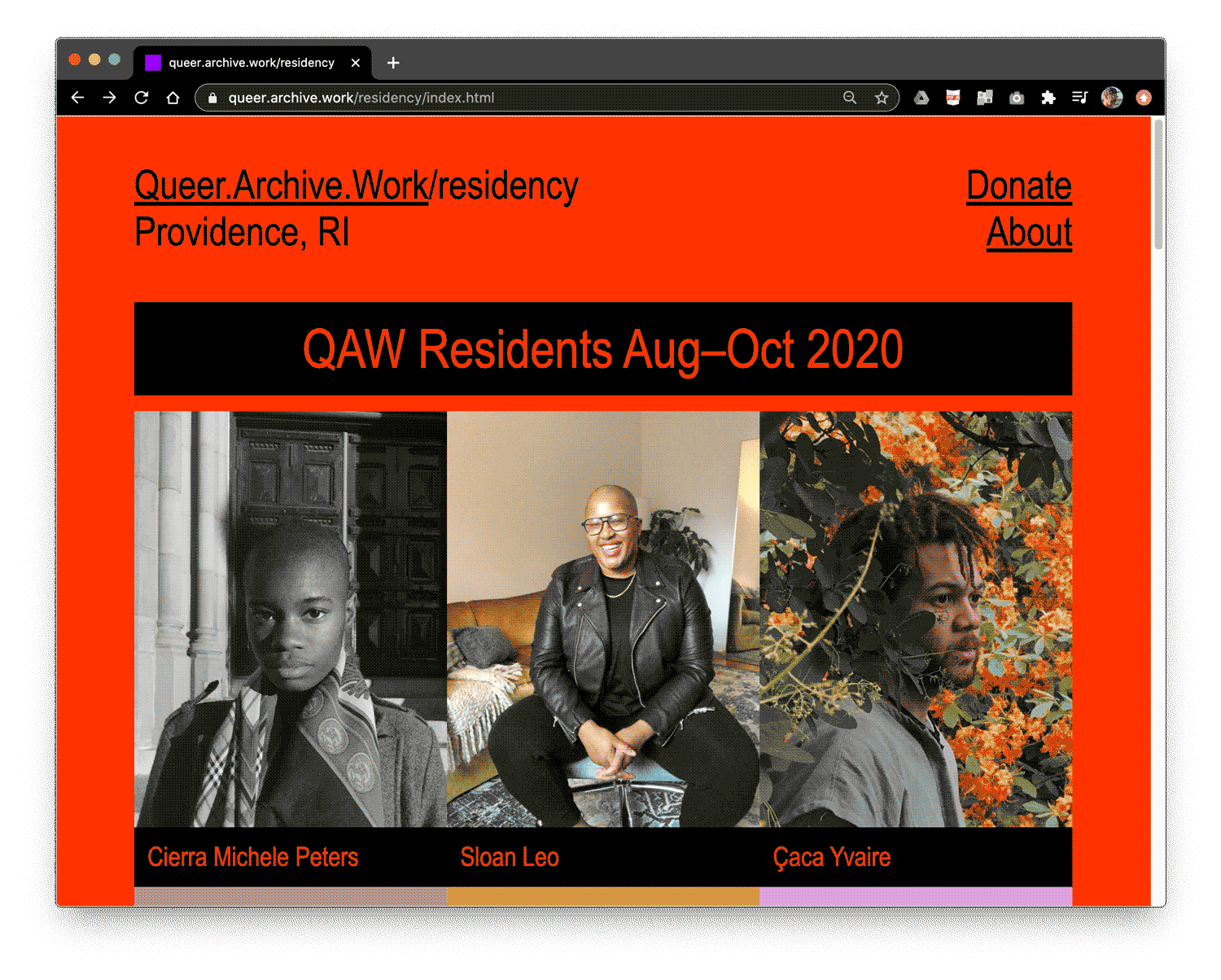

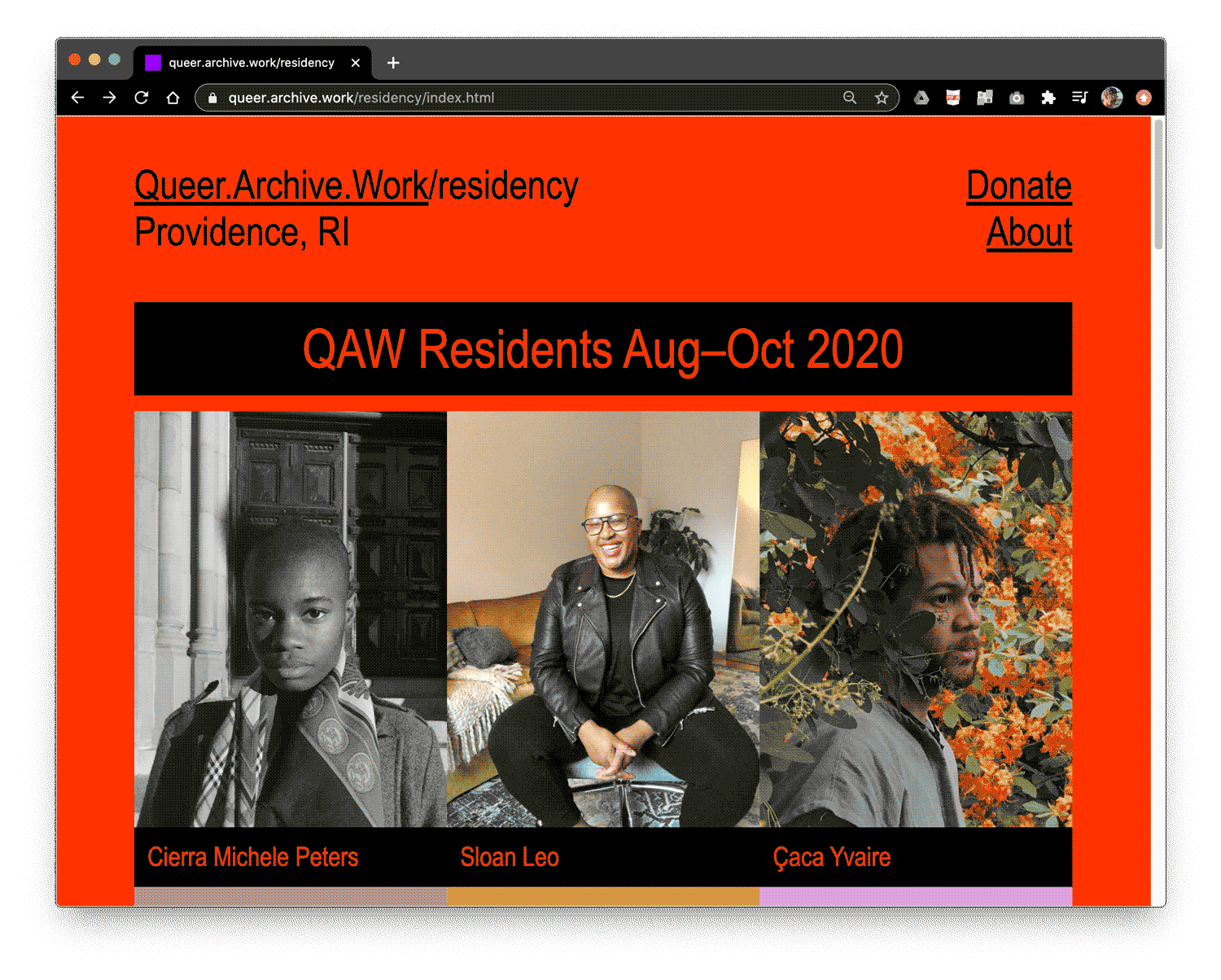

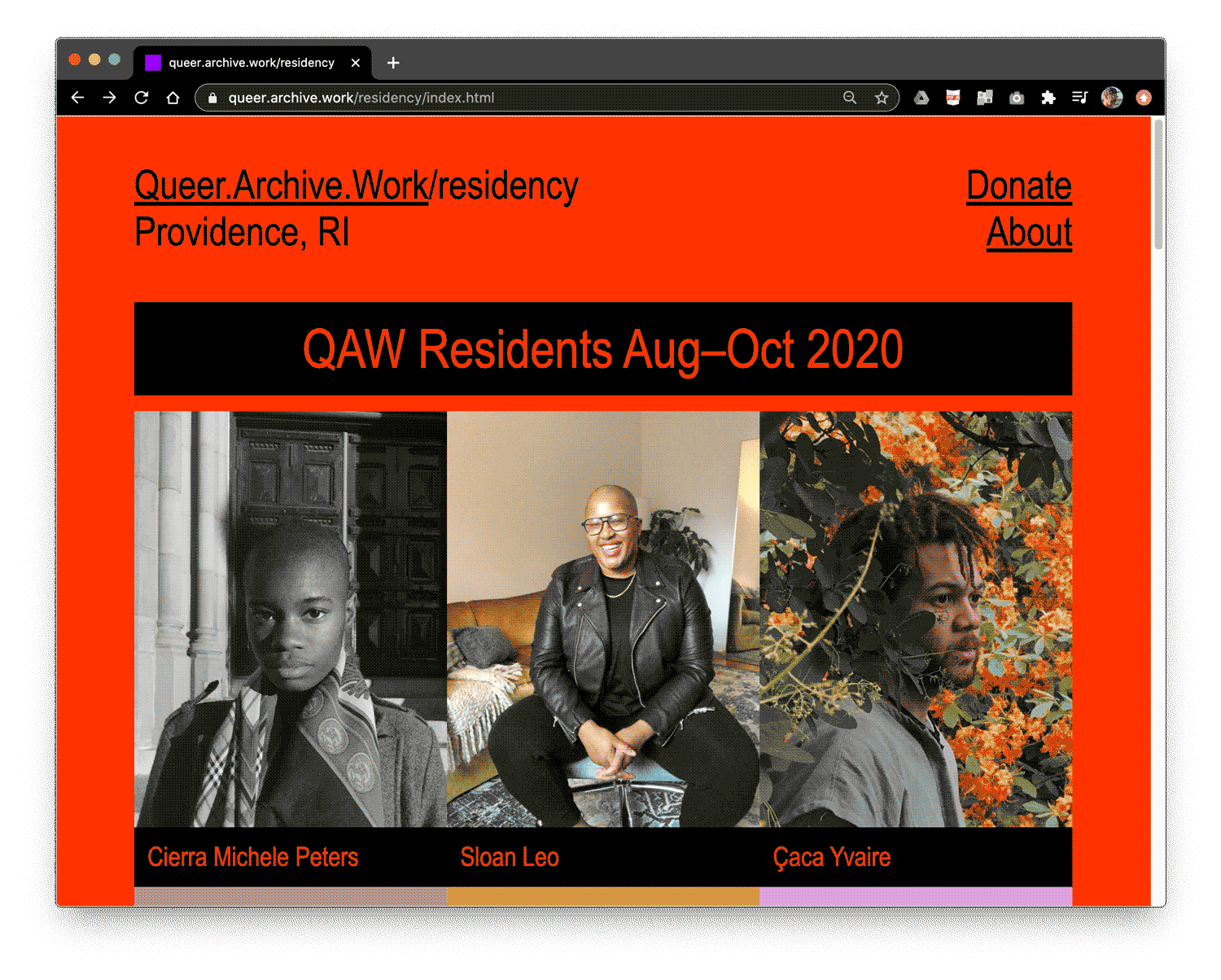

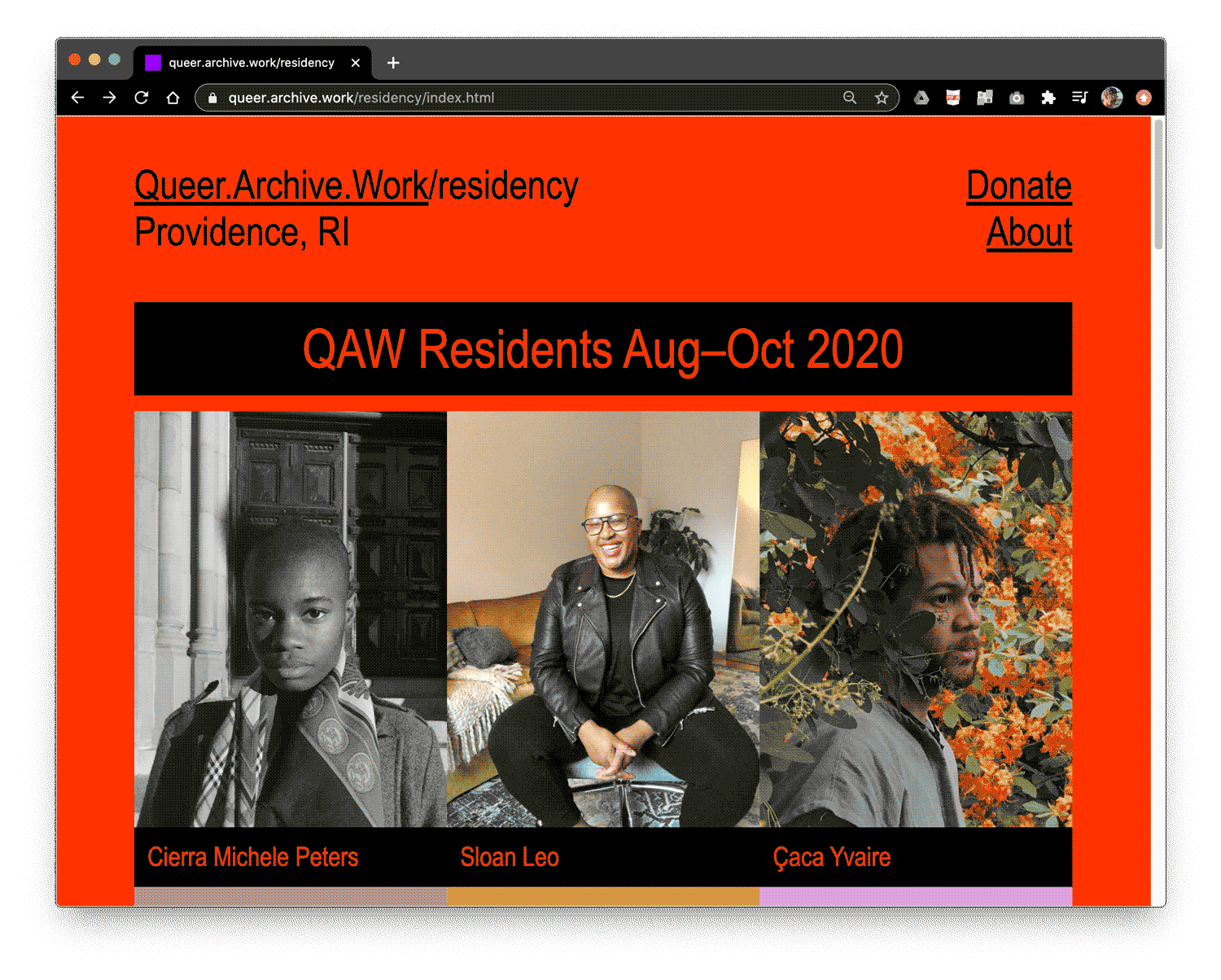

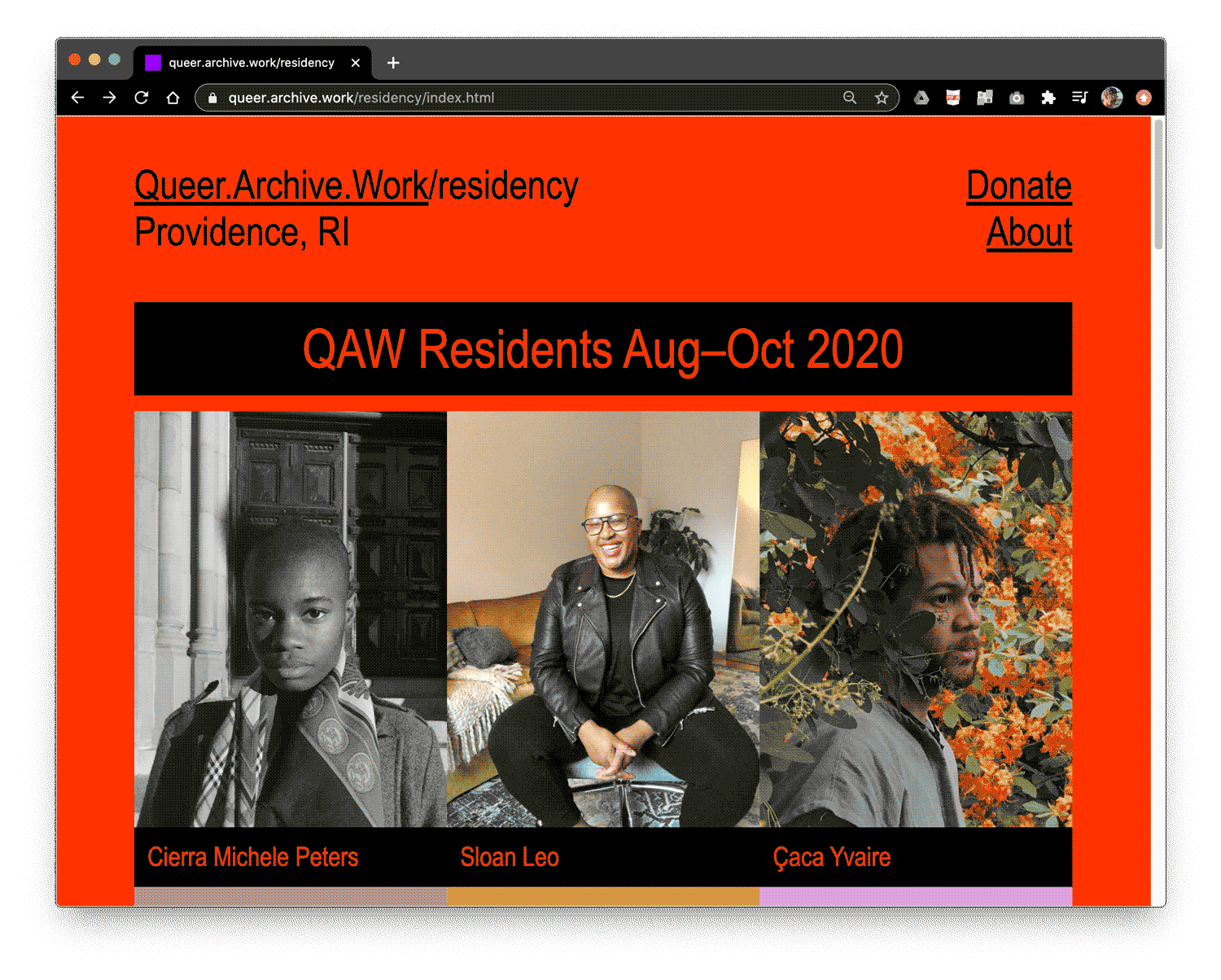

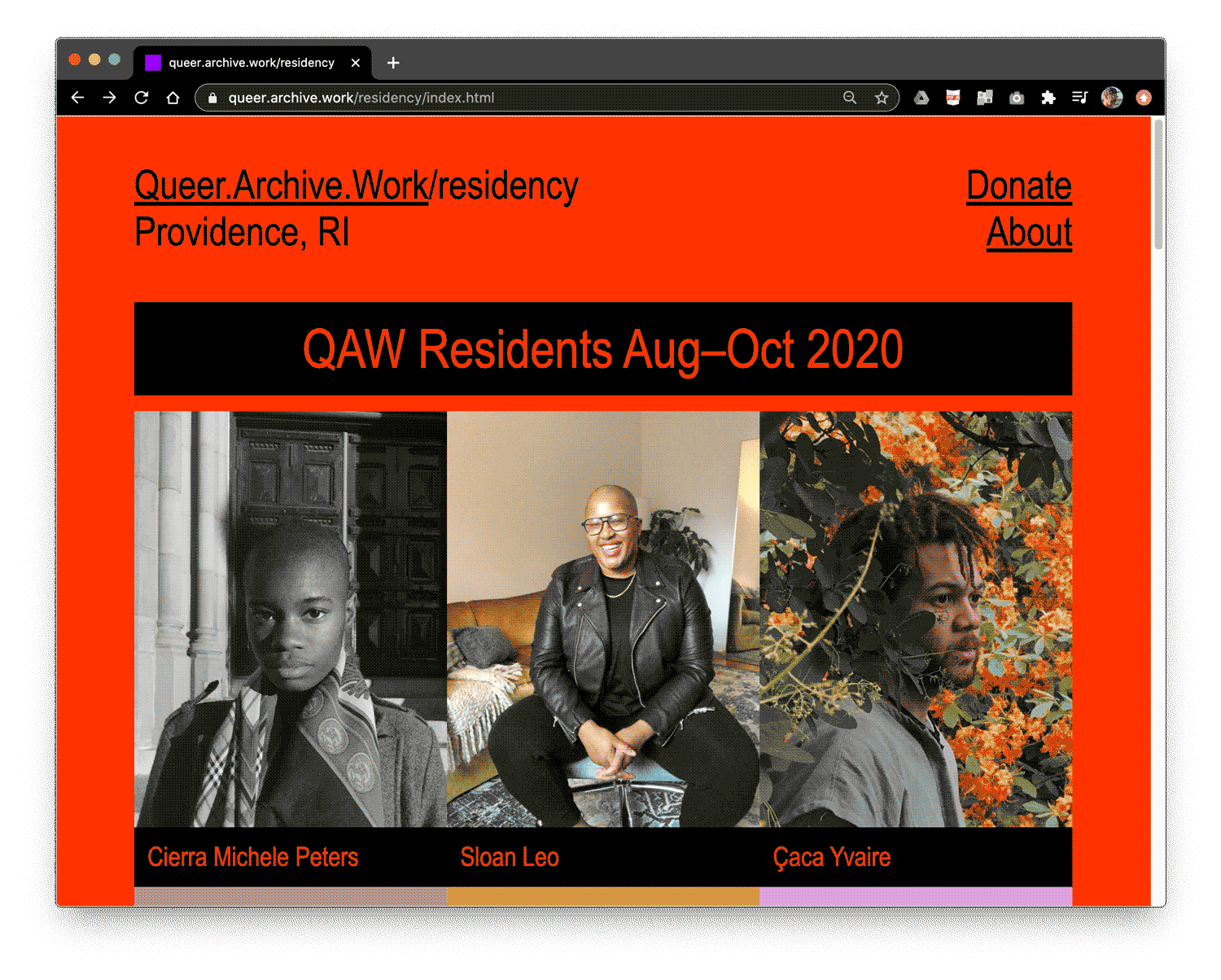

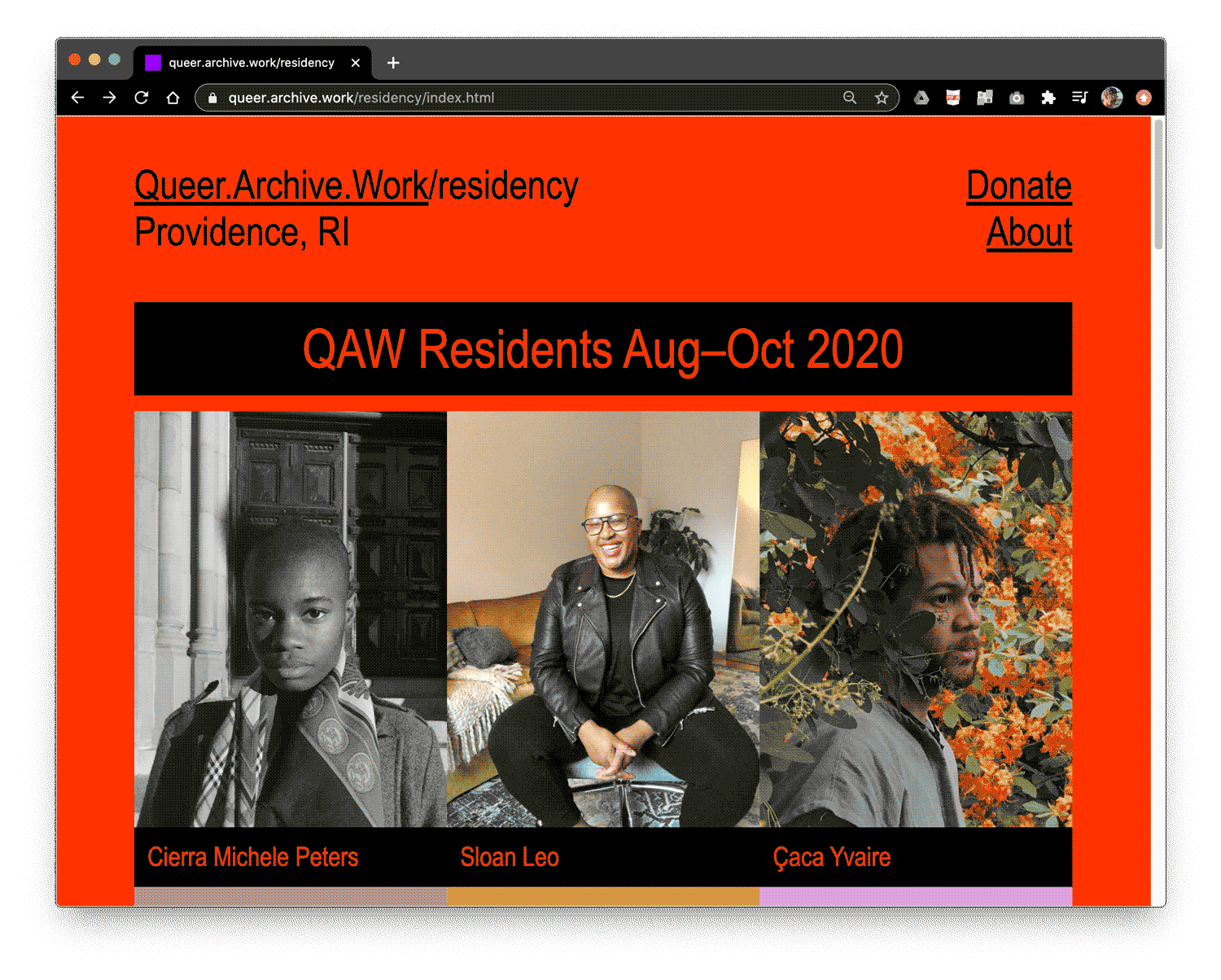

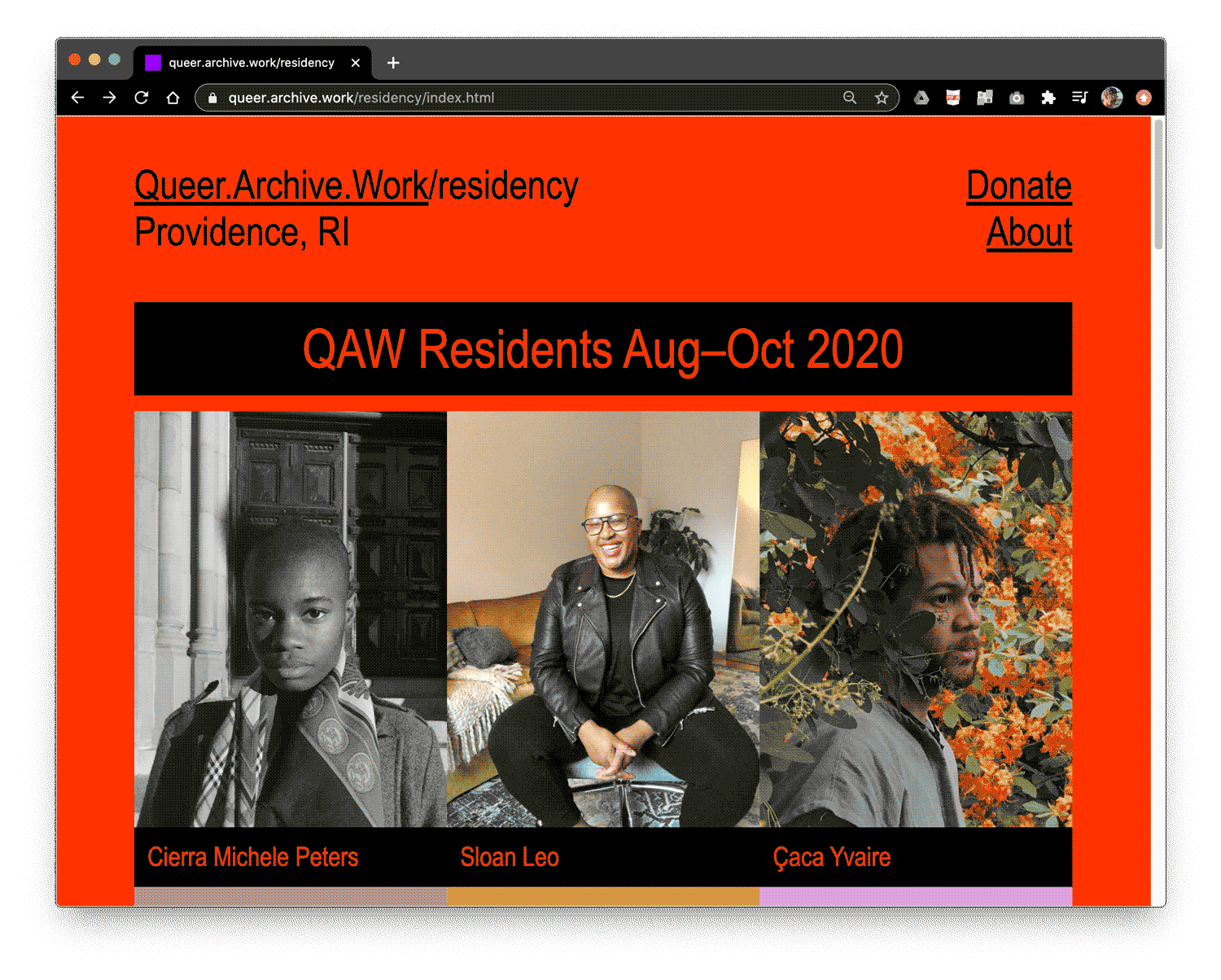

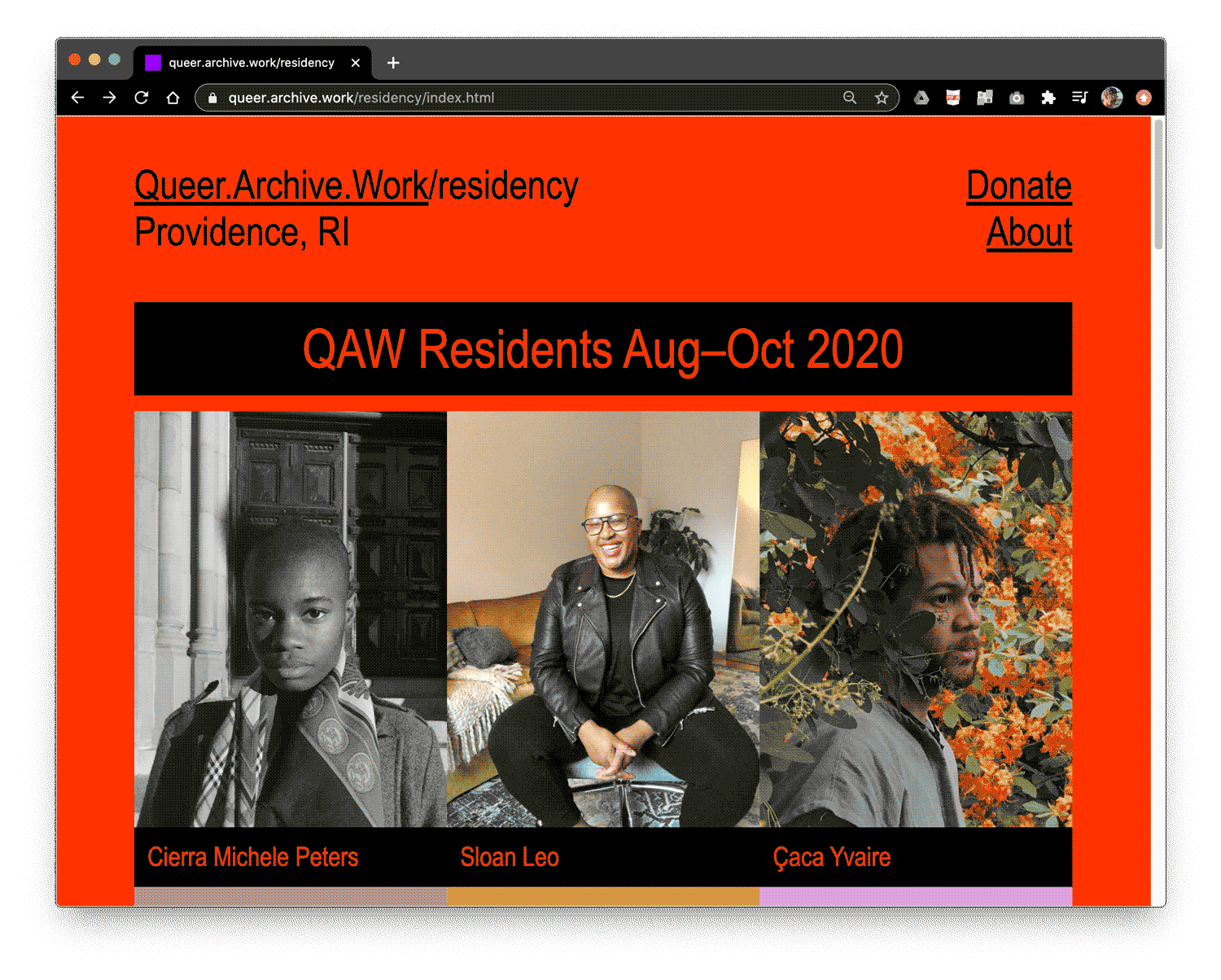

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

Press Press, toolkit.press

I will talk about how I’ve been working, and what I’ve been doing in 2020, but first I’ll approach that work through some of the values that I’m prioritizing right now, as an artist-publisher, as an educator, as someone who is trying to support the radical work that I see happening around me, in response to these intersecting crises.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, streamed live on July 9, 2020

Recently, I was able to tune into a talk by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, who were discussing their new text “the university: last words,” which is in part a response to their classic work “The University and the Undercommons” (2004). A lot was covered in this discussion, but the phrase I keep coming back to and thinking about is shared practice.

Michael Rock, Designer as Author (1996)

In the talk, Dr. Moten speaks about the beauty of shared practice over individual roles, and I’ve been thinking about what this might mean specifically in the context of art and design schools, where we’ve been taught, and where we continue to teach, at least where I teach, about the transformative power of individual expression. The power of the artist or the designer as author, and the values that naturally go along with this successful figure: ambition, competition, profit, ownership, self-sufficiency, and domination.

R.I.S.E. Indigenous, 4/5/20

We have no choice but to teach these values because they’re deeply embedded within these imperial institutions, keeping alive the promise of professional success, a promise that’s designed to drive everyone towards the same goal: the credential. A degree, be it a BFA or an MFA or a PhD, and the power that degree gives not just to participate in capitalism but to accelerate within it and reproduce its violence.

RISD’s call for “radical imagination” within its COVID-19 remote learning announcement, 3/15/20

In our teaching, we prioritize this value of exceptionalism because it’s required by the extractive practices of the art and design worlds. Ultimately, students learn that to be successful is to be sovereign—a supreme, independent power without any need to depend upon anyone or anything, be it kin or community or state, unless it’s for profit.

PS notes, Fred Moten & Stefano Harney talk, July 9, 2020

Instead, what would it look like to teach, as Dr. Moten said, “the shared practice of fulfilling needs together as a kind of wealth—distinguishing and cultivating the wealth of our needs, rather than imagining that it’s possible to eliminate them.” This resonates deeply with me right now, and it challenges me to pivot my own practice, away from the institution: towards collective work, radical un-learning, the redistribution of resources, and communal care. From my work ---->>> to our work.

COVID-19 Mutual Aid (Greater Los Angeles and beyond), Google Doc, March 2020

When I look back at so many urgent artifacts produced this year in crisis, the more powerful ones operate in this realm of shared practice. These are artifacts that step away from individual authorship, towards something larger—collective, cooperative works emerging from the shared wealth of needs.

“IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.,” jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs.

And I think about David Wojnarowicz’s jacket here, worn by him at an ACT UP demonstration 32 years ago, during a different pandemic. It’s certainly an individual expression, but I see it first as an act of protest, speaking within and on behalf of the collective, and then as a gesture of publishing, manifesting an urgent message in public space, using the very body that is the subject of that message, the body that will die of the disease, as the platform for its dissemination. This jacket is so many things. It’s art, it’s graphic design, it’s a shared plea, it’s a protest at a very particular moment. It’s an urgent artifact.

Asian American Feminist Collective zine

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts, the proof that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

RISD Anti-Racism Coalition (risdARC), student-run initiative launched July 1, 2020

A letter from some junior BIPoC faculty regarding Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD, July 8, 2020

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, collaborative mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

Michael Rock, Designer as Author (1996)

In the talk, Dr. Moten speaks about the beauty of shared practice over individual roles, and I’ve been thinking about what this might mean specifically in the context of art and design schools, where we’ve been taught, and where we continue to teach, at least where I teach, about the transformative power of individual expression. The power of the artist or the designer as author, and the values that naturally go along with this successful figure: ambition, competition, profit, ownership, self-sufficiency, and domination.

R.I.S.E. Indigenous, 4/5/20

We have no choice but to teach these values because they’re deeply embedded within these imperial institutions, keeping alive the promise of professional success, a promise that’s designed to drive everyone towards the same goal: the credential. A degree, be it a BFA or an MFA or a PhD, and the power that degree gives not just to participate in capitalism but to accelerate within it and reproduce its violence.

RISD’s call for “radical imagination” within its COVID-19 remote learning announcement, 3/15/20

In our teaching, we prioritize this value of exceptionalism because it’s required by the extractive practices of the art and design worlds. Ultimately, students learn that to be successful is to be sovereign—a supreme, independent power without any need to depend upon anyone or anything, be it kin or community or state, unless it’s for profit.

PS notes, Fred Moten & Stefano Harney talk, July 9, 2020

Instead, what would it look like to teach, as Dr. Moten said, “the shared practice of fulfilling needs together as a kind of wealth—distinguishing and cultivating the wealth of our needs, rather than imagining that it’s possible to eliminate them.” This resonates deeply with me right now, and it challenges me to pivot my own practice, away from the institution: towards collective work, radical un-learning, the redistribution of resources, and communal care. From my work ---->>> to our work.

COVID-19 Mutual Aid (Greater Los Angeles and beyond), Google Doc, March 2020

When I look back at so many urgent artifacts produced this year in crisis, the more powerful ones operate in this realm of shared practice. These are artifacts that step away from individual authorship, towards something larger—collective, cooperative works emerging from the shared wealth of needs.

“IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.,” jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs.

And I think about David Wojnarowicz’s jacket here, worn by him at an ACT UP demonstration 32 years ago, during a different pandemic. It’s certainly an individual expression, but I see it first as an act of protest, speaking within and on behalf of the collective, and then as a gesture of publishing, manifesting an urgent message in public space, using the very body that is the subject of that message, the body that will die of the disease, as the platform for its dissemination. This jacket is so many things. It’s art, it’s graphic design, it’s a shared plea, it’s a protest at a very particular moment. It’s an urgent artifact.

Asian American Feminist Collective zine

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts, the proof that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

RISD Anti-Racism Coalition (risdARC), student-run initiative launched July 1, 2020

A letter from some junior BIPoC faculty regarding Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD, July 8, 2020

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, collaborative mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

RISD’s call for “radical imagination” within its COVID-19 remote learning announcement, 3/15/20

In our teaching, we prioritize this value of exceptionalism because it’s required by the extractive practices of the art and design worlds. Ultimately, students learn that to be successful is to be sovereign—a supreme, independent power without any need to depend upon anyone or anything, be it kin or community or state, unless it’s for profit.

PS notes, Fred Moten & Stefano Harney talk, July 9, 2020

Instead, what would it look like to teach, as Dr. Moten said, “the shared practice of fulfilling needs together as a kind of wealth—distinguishing and cultivating the wealth of our needs, rather than imagining that it’s possible to eliminate them.” This resonates deeply with me right now, and it challenges me to pivot my own practice, away from the institution: towards collective work, radical un-learning, the redistribution of resources, and communal care. From my work ---->>> to our work.

COVID-19 Mutual Aid (Greater Los Angeles and beyond), Google Doc, March 2020

When I look back at so many urgent artifacts produced this year in crisis, the more powerful ones operate in this realm of shared practice. These are artifacts that step away from individual authorship, towards something larger—collective, cooperative works emerging from the shared wealth of needs.

“IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.,” jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs.

And I think about David Wojnarowicz’s jacket here, worn by him at an ACT UP demonstration 32 years ago, during a different pandemic. It’s certainly an individual expression, but I see it first as an act of protest, speaking within and on behalf of the collective, and then as a gesture of publishing, manifesting an urgent message in public space, using the very body that is the subject of that message, the body that will die of the disease, as the platform for its dissemination. This jacket is so many things. It’s art, it’s graphic design, it’s a shared plea, it’s a protest at a very particular moment. It’s an urgent artifact.

Asian American Feminist Collective zine

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts, the proof that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

RISD Anti-Racism Coalition (risdARC), student-run initiative launched July 1, 2020

A letter from some junior BIPoC faculty regarding Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD, July 8, 2020

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, collaborative mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

COVID-19 Mutual Aid (Greater Los Angeles and beyond), Google Doc, March 2020

When I look back at so many urgent artifacts produced this year in crisis, the more powerful ones operate in this realm of shared practice. These are artifacts that step away from individual authorship, towards something larger—collective, cooperative works emerging from the shared wealth of needs.

“IF I DIE OF AIDS - FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.,” jacket worn by David Wojnarowicz (September 14, 1954–July 22, 1992), ACT UP demonstration, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs.

And I think about David Wojnarowicz’s jacket here, worn by him at an ACT UP demonstration 32 years ago, during a different pandemic. It’s certainly an individual expression, but I see it first as an act of protest, speaking within and on behalf of the collective, and then as a gesture of publishing, manifesting an urgent message in public space, using the very body that is the subject of that message, the body that will die of the disease, as the platform for its dissemination. This jacket is so many things. It’s art, it’s graphic design, it’s a shared plea, it’s a protest at a very particular moment. It’s an urgent artifact.

Asian American Feminist Collective zine

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts, the proof that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

RISD Anti-Racism Coalition (risdARC), student-run initiative launched July 1, 2020

A letter from some junior BIPoC faculty regarding Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD, July 8, 2020

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, collaborative mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

Asian American Feminist Collective zine

Urgent artifacts are the materials we need when gaslighting happens—the receipts, the proof that demonstrates how crisis compounds crisis. A record of the moment with a call-to-action: an instruction or invitation to engage, to provide aid, to push back, to refuse, to resist.

RISD Anti-Racism Coalition (risdARC), student-run initiative launched July 1, 2020

A letter from some junior BIPoC faculty regarding Institutionally racist hiring practices at RISD, July 8, 2020

These urgent artifacts might be protest materials, collaborative mutual aid spreadsheets, survival guides, syllabi, online petitions, manifestos, demands,

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

letter-writing, performances, lists of resources, messages worn in public, fliers posted in public, teach-ins, an assembling of poetry, or quickly made zines.

Demian DinéYazhi´, Counterpublic, St. Louis, 2019

Urgent artifacts are meaningless without distribution, publics, and circulation, which means that to talk of urgent artifacts is to talk about publishing: spreading information, circulating demands, or simply expressing the moment in public despite structural failure.

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA

These are spaces and practices that refuse to replicate or support the matrix of domination (heteronormativity, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and capitalism). These agitators don’t wait for a crisis to peak: their work is slow and persistent, prioritizing communal care as an urgent, never-ending practice.

Urgentcraft print, 2019

We’re faced with a kind of doom right now that sometimes feels like the end of the story. So here’s what we can do. In our own work, whether it be art, design, or otherwise: use what we have, whatever is right in front of us. Don’t wait for the next wave of crisis. Strengthen our networks now, so that when another flash point happens we’re prepared to connect, to call, and to respond, to gather, and to be in it together, whatever that means to you. Map our needs. Map our assets. What are our resources? How will we share our abundance? Be generous in how, what, and with whom we share, because in these moments of exchange, communities form. Use the urgentcraft principles, re-shape them, add to them, share them. If nothing else, keep them around, as a reminder that art and design can be used to loosen power.

Thank you.

paul@soulellis.com

They depend upon the same platforms and tools and modalities used in everyday publishing, from social media to copy machines to silkscreen printing to Github. Urgent artifacts aren’t precious or difficult to access; they’re modest, easily made, and they’re located where the conversations are already happening.

Anakbayan Los Angeles, April 2, 2020

Could we characterize these creative acts of labor—documenting, agitating, redistributing, and interfering with power—as urgentcraft? Urgentcraft today looks like protest happening on Instagram or Animal Crossing, or student-made websites that collect anti-racism demands, or a collaborative zine made by a US congressperson and a prison abolitionist about mutual aid.

“Design perfection”

Urgentcraft exists outside of the design world, outside of brilliance, perfect legibility, otherworldly craft, extractive practices, and profit at all costs. Urgentcraft interrupts the smooth flow of design perfection. It is not an aesthetic.

Urgentcraft

Rather, I offer up urgentcraft as a set of principles, a way of working that’s focused on communal care and shared practices that resist oppression-based design ideologies, especially for art and design students and educators. Here they are, and I get into them more thoroughly here. If you’d like to come back to this, we can discuss them in more detail later.

Do what you can

Use modest tools and materials

Understand the politics of your platforms

Practice media hybridity

Work in public (self-publish!)

Practice a slow approach to fast making

Think big but make small

Redistribute wealth and accumulation

Work towards the then and there of queer futurity (while acknowledging past struggles and privileges)

Agitate/interfere (“make good trouble”)

Dismantle white supremacy / be anti-racist

Resist, loosen, and dismantle ableism, heteropatriarchy, and settler colonialism

Resist capitalist strategies

Refuse design perfection / stay with the mess

Question linearity and other hierarchical structures

Commit to maintenance and self-care as a form of urgency

Fail to provide the perfect read (resist legibility)

Use (steal from) the institution when you can (while resisting its values) (Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons”)

Prioritize communal care as a never-ending practice

Queering the Map

Words like artifact, evidence, document, and record suggest that the archive might also be an important concept here. Not conventional archives like the ones we know within universities or museums, but a place where we can dig into and learn from stories that are typically minimized or erased completely from mainstream narratives. Wayward stories (after Saidiya Hartman), stories of failure (after Jack Halberstam), queer and trans stories, Black stories, Indigenous stories, POC stories, disabled stories, immigrant stories. What would an archive devoted to these kinds of voices look like?

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

Here is one such space, which is a physical place I opened earlier this year, called Queer.Archive.Work. It emerged from a series of collaborative publications that I’ve produced over the last few years, works that assemble artists and writers into loose publications that resist linearity and fixed narratives.

Urgency Reader 2 (April 2020)

The first thing I did at Queer.Archive.Work was gather 110 artists and writers into a volume of unbound work produced during quarantine, called Urgency Reader 2. It was published this past April, with sales benefiting the space.

I used an individual artist’s grant that I received from the State of Rhode Island to compensate each of the contributors, many of whom donated the funds back to the pool, resulting in a more meaningful, equitable distribution of funds, which I loosely called mutual-aid publishing.

Queer.Archive.Work library

Queer.Archive.Work is now a non-profit organization, with a mission to support artists and writers through queer publishing. It’s an anti-racist community reading room, with a small library of experimental publishing;

Nora Khan at work, open house printing at Queer.Archive.Work, March 2020

it’s a publishing studio, with a risograph machine and inks and papers and binding equipment; and it’s a project space. And it’s also a 501(c)(3) bank account, where we raise funds from grants and individual donations to redistribute to artists in need.

Queer.Archive.Work Residents Aug–Oct 2020

We just launched our first-ever artists’ residency program, with 10 artists joining us over the next year, each occupying the studio and taking over to produce their own work. The residency comes with funding, materials, and supplies, and a key to the space. Here are the first three residents: Cierra Michele Peters, Sloan Leo, and Çaca Yvaire.

Queer.Archive.Work, Providence, RI

For me, this is what shared practice looks like right now: porous space as platform, providing access to tools that empower to realize work in new ways. Our work right now is to make this platform safe, accessible, and anti-racist, operating outside of, and counter to, legacy institutions like commercial galleries, museums, and art and design schools.

2727 California Street, Berkeley, CA

Queer.Archive.Work is directly inspired by other artist-run spaces and projects that are already doing this, and have been for awhile. Spaces like Wendy’s Subway, ZINE COOP, Press Press, 2727 California Street, Soft Surplus, Dispersed Holdings, Dirt Palace, LACA, RISE Indigenous, Homie House Press, The Bettys, BUFU, Asian American Feminist Collective, Endless Editions, Hyperlink Press, Other Publishing, GenderFail, Unity Press, and the just-launched Dark Study, among many others.

Unity Press, Oakland, CA